Delving into the archives: energy in days gone by

Accounts reveal a centuries-old struggle to fend off the Fenland cold and bring light and warmth to the lives of the St John’s community

The mental image of the shivering student in a freezing garret, peering at his books by candlelight, is perhaps as old as scholarship itself. But how true a reflection is it of life at St John’s in the days before central heating and electricity?

As the College takes steps towards more sustainable energy consumption, and addresses the wider theme of energy in an online series of articles, a dip into the archives reveals a centuries-old struggle to fend off the Fenland cold and bring light and warmth to the lives of the St John’s community.

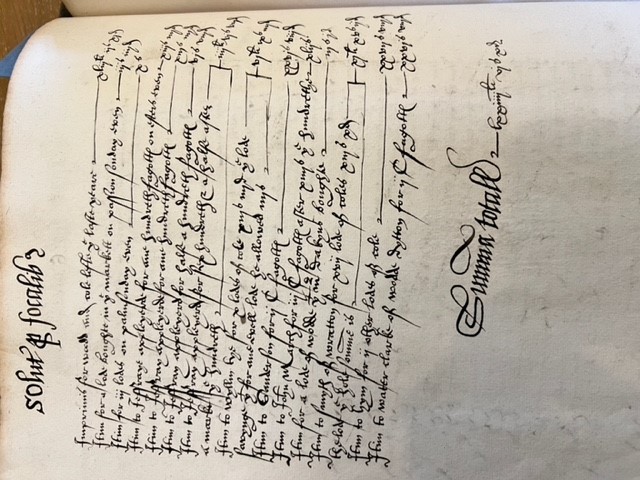

A series of account books, known as ‘rentals’, dating back to the 16th century contains regular entries for fuel needed to heat the College’s earliest buildings, including the Hall and student accommodation. In 1557, almost five decades after St John’s foundation, one of the books records £43, two shillings and sixpence spent on wood and coal. Orders included a load of wood ‘bought in the market on Passion Sunday even [evening]’ and three loads on Palm Sunday, perhaps suggesting extra investment in heating and fuel for cooking during religious festivals. Geoffrey Appleyard, who was paid ‘on Easter eve’, was one of several suppliers of wood faggots – bundles of brushwood bound together used for strengthening riverbanks or creating revetments – while a Mr Smith of Wratton provided 17 loads of coal at 13 shillings and fivepence a load.

In 1559, a sequence of entries illustrates the process by which the College acquired wood for burning. It paid £3, six shillings and eight pence for a half-acre of woodland in Weston Colville, a village 10 miles south-east of Cambridge. A further eight shillings paid for the felling of the trees and a fee for a Mr Tye who managed the work, with 14 shillings more to have the trunks chopped into faggots and logs.

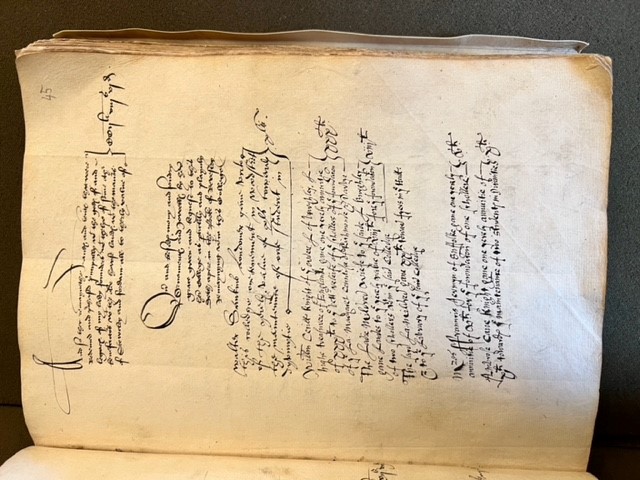

In the depths of winter, the draughty College buildings would still have proved chilly for long-suffering students. Benefactors sometimes took pity on the freezing scholars: a Register of Inventories from the 1580s kept in the archives reveals that Lady Burghley – Mildred Cecil, wife of Sir William Cecil, Lord High Treasurer of England – donated £20 for ‘fires in the Hall’ from November to February.

During the bitter winters of the 17th century, in the midst of the ‘little ice age’, rooms in the student accommodation were seldom easy to heat

Wood was not the only fuel used at St John’s – coal fires warmed the College right up until the 1940s. During the bitter winters of the 17th century, in the midst of the ‘little ice age’ that gripped northern Europe for 200 years, rooms in the student accommodation known as the labyrinth and even in the main Courts were seldom easy to heat. College accounts repeatedly refer to ‘seacoal’, which was brought south by sea from Newcastle and inland along the Ouse river network. The coal was delivered in units known as ‘chalders’ – an English measure of dry volume rather than weight, derived from an obsolete spelling of the word ‘cauldron’.

Account books reveal that in 1614, the cost of maintaining fires at the College amounted to £111.17s.9d. The sum was split into just over £57 on charcoal, £34 on seacoal, and the rest on two more ancient fuels: £4 on sedge (a plant traditionally grown in the Cambridgeshire fens) and the last £15 on ‘turves’ or turf, which was kept in special turf cupboards and stores in College. The money was recouped directly from those who benefited – Fellows, Scholars and students – and, according to the official St John’s College, Cambridge: A History (edited by Dr Peter Linehan, The Boydell Press, 2011), the aim seems to have been to break even rather than profit from the arrangement.

As an undergraduate, James Wood ‘read by a candle on the stairs with his feet in straw, being too poor to afford a light or fire’

In his Portrait of a College: A History of the College of Saint John the Evangelist in Cambridge (Cambridge University Press, 1961), Edward Miller recounts the bleak experience of James Wood. Mr Wood arrived at the College as a poor sizar (an undergraduate who receives financial help from the College, in some cases in return for menial duties), but rose to be Master from 1815 to 1839. “As an undergraduate he kept in a garret called the Tub at the top of O staircase Second Court, and read by a candle on the stairs with his feet in straw, being too poor to afford a light or fire.”

In 1898, for the first time in its history, the College was unable to let all its rooms – partly because of a fall in undergraduate numbers but also because of the dilapidated state of the accommodation, much of it lined with dark and gloomy panelling. According to the Dr Linehan’s College History: “Many of the sets were bitterly cold, especially those in high ceilinged New Court, where condensation dripped down the walls in winter. There was therefore an increasing tendency for local students to live with their parents, and for others to live out of College, where they might take baths and read by electric light.”

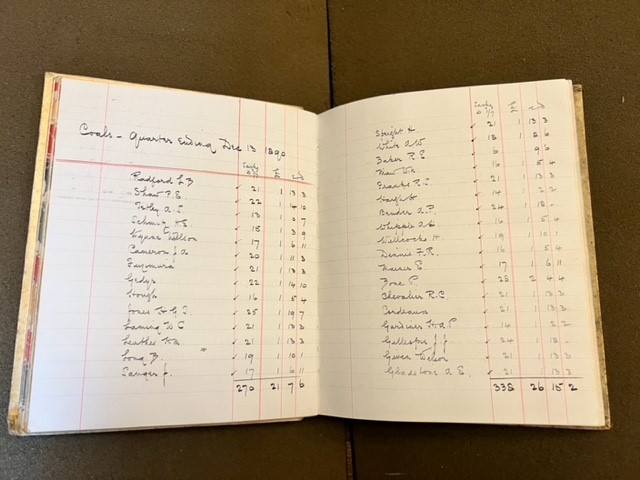

Those students unable to move out paid for their own fuel. Coal ledgers in the archives, dating from 1860 to 1905, record the number of sacks of coal pupils used and the bills paid each quarter. The kitchen stoves were still coal-fired in 1914, when Alf Sadler, who would go on to be kitchen manager, began work as an apprentice. Mr Sadler recalled how men playing football would come to the kitchens and buy buckets of hot water for washing. Hip baths were used in student rooms and gyps (male College servants) took up hot water for Fellows.

The turn of the 19th century brought a landmark change in energy supply at St John’s: the introduction of electric lighting. Where once candles, lanterns and – later – gas lamps had served to illuminate the buildings (the Great Gate was lit by ‘a lanterne’ even in the 17th century during the darker months), the fiercer brightness of electric bulbs now banished shadows from the College. The exception to the rule is in the Combination Room, which to this day still does not have electricity.

“An Old Johnian, revisiting the College, will no longer fumble for his sport keyhole in the dark recesses of his ancient haunts, for he will find a brilliant and unexpected light on the stairs he knows so well”

In 1892, some 12 years after the invention of the incandescent light bulb and just a year after the introduction of electric lighting in the city of Cambridge using a turbine generator designed by Johnian engineer Sir Charles Parsons, the College Council agree to wire the Hall, Chapel and Undergraduates’ Reading Room for light. In 1908 the then-Master Sir Robert Forsyth Scott added the Master’s Lodge to the list.

However, it was not until 1912 that student rooms were finally wired for electric light, making St John’s one of the last Colleges to adopt the technology. The delay, an article in the 1911/12 edition of The Eagle insisted, had enabled it to take advantage of ‘many advances in electrical engineering’, adding boldly: “It is not too much to say that no installation could exceed ours as regards both efficiency and safety.”

The installation, by which electrical current was brought to a ‘Transformer House’ in Kitchen Lane near the old bridge and then ‘delivered to the several Courts at a pressure of 205 volts’, was a significant operation, costing some £4,000. Three-quarters of a mile of underground cable was laid, together with no fewer than 17 miles of room wiring. Each staircase was wired like a separate house, with cut-out switches and fuse-boxes ensuring a failure in an individual room or staircase would not affect its neighbours, and current was supplied to each room at 100 volts. Each undergraduate set received one pendant-lamp of 25 watts, giving a light equivalent to 22 candles, a reading-lamp of 17 watts, or 14 candles, and a bedroom-lamp of 17 watts, ‘all of Osram make’. Although the College covered the costs of wiring Fellows’ rooms, it was up to the individual Fellows to pay for the fixtures.

Lecture rooms were also lit by electricity, ‘which is certainly a wholesome improvement on the old gas system’, an observer wrote in The Eagle. Nevertheless, although the article remarked that ‘the convenience and comfort of the light have already been appreciated by everyone’, electrification created a dramatic change in atmosphere within the Courts, with four centuries of flickering shadows gone forever: “The small paraffin lamps which have lighted the staircases of the old Courts for so many years have at last disappeared, and an Old Johnian, revisiting the College, will no longer fumble for his sport keyhole in the dark recesses of his ancient haunts, for he will find a brilliant and unexpected light on the stairs he knows so well.”

Today, brightness and warmth at the College are taken for granted, yet change and innovation in the use of energy never stops. St John’s sustainability strategy aims to decarbonise College heating by shifting from gas to green electricity, generated from ground source heat pumps or even – potentially – the heat of the River Cam.

Read more about modern-day advances in Energy at St John’s

Published 25/5/2023