Self-isolation blogs: Matthew Seah

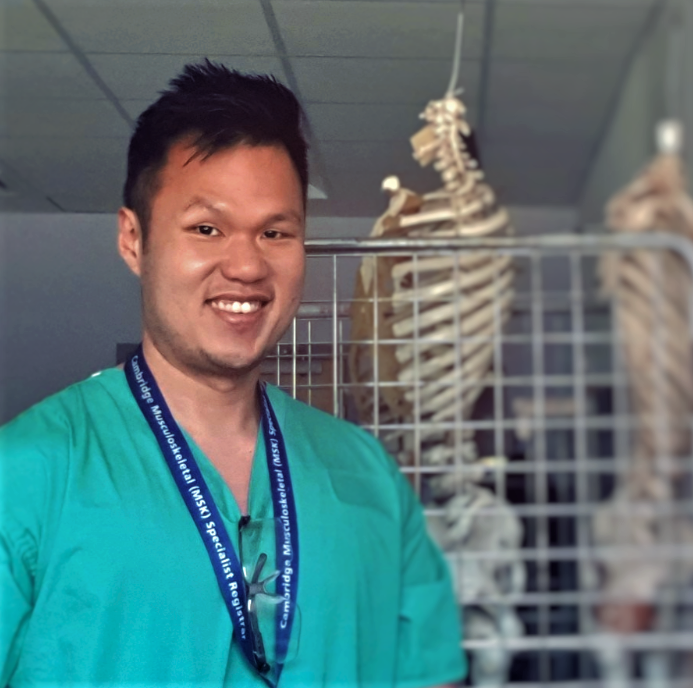

Matthew Seah

This is part of a series of self-isolation blogs, written by students, staff and Fellows during the coronavirus pandemic so we can learn about their experiences.

To view other blog entries, take a look at our main self-isolation blog page.

The posts below are from Matthew Seah, an orthopaedic surgeon who worked at Addenbrooke's Hospital for a few years before starting his PhD at John's, where he is currently in his 2nd year. He is now pausing his studies temporarily to help with the Addenbrooke's Covid19 efforts.

Week 6

I do hope I've not become completely socially inept with all this isolation.

It might seem like I have a way with words (not really), but I open my mouth to change feet with some degree of frequency. That is to say, sometimes I'm a big idiot. Most of my little gaffes are innocuous enough and some occasionally provoke a reaction from strangers who are seated next to me at Hall. But every now and then my mouth moves much faster than my brain can process what comes out of it.

What throws me off more than anything else is seeing someone out of context. It generates one of those "Where do I know you from?" moments from which it is very difficult for me to recover.

I was in a supermarket recently when an attractive lady with a big smile approached me. She looked somehow familiar, and I knew I knew her, but I couldn't for the life of me figure out how. I immediately challenged my brain to figure it out, but my brain was just not up to the task.

We started chatting, and my brain continued doing cart-wheels trying to figure out just who she was. Finally, she mentioned the hospital and at last a synapse made a connection in my head. 'She's a theatre nurse! You work with her - that's it!'

I was so used to seeing her in her scrubs that I hadn't recognised her out of context in her street clothes. The feeling of utter relief at my brain's triumph was overwhelming. So overwhelming that my brain temporarily (but completely) shut down while I continued to speak.

"Oh, so this is what you look like with clothes on!"

Dead silence.

I'm not sure who blushed more furiously - me or her. I then started laughing, one of those nervous, "What did I just say?" kind of laughs. Thankfully she saw the funny side of it too, but I'm not sure I can say the same about the others in the supermarket!

27 April 2020

Week 5

It’s 6.05 am. The hospital is just starting to wake up from its slumber, stretching arms and blinking eyes. I’m still a couple of hours away from the end of another night shift.

Night shifts are curious creatures. They are a part of the fabric of hospital life — one of the oft-hated aspects of our jobs. They steal us away from our ‘regular’ lives, cutting short bedtime and gym time so we may await other people and their needs. Night shifts throw off the easy rhythm of days, forcing us to hide in dark rooms as we chase sleep and miss the sunlight. There are many ways to try to fit nights into life, and none of them work well. No matter how I toss and turn it, I trade missed days for bleary-eyed short tempers and a vague feeling of nausea.

The hospital is weirdly bright and quiet at night. There is activity, but it’s hidden behind doors and curtains and shushed for the neighbours. You wander the halls in search of a source of caffeine, slinking down corridors filled with people you plucked from their lives and installed into your healthcare assembly line. Monitors beep. And alarms occasionally go off. They shatter that tiny bit of sleep you’d started to catch in your chair. Muffled clicks of computers and quiet conversations tease your ears, co-worker confessions brought out by the intimacy of a night shift.

Through it all, patients come. As each one checks in, I bristle slightly. Why aren’t you asleep? Get back to bed! The Emergency Department shift is always an adventure but in the night, there are common visitors. Babies who won’t stop crying. Adults who won’t stop drinking. There is often a helpless victim of assault. Just like your mum said, nothing good happens after midnight.

Danger indeed lurks in the early dawn light. Our relative inner calm is interrupted by the ambulance crew alerting the resuscitation room to say they are bringing Patient X (not their real name) in after a gunshot injury.

Have you noticed how people on screen die immediately after getting shot or stabbed? Or they have their last few gasps before divulging the name of their killer or something equally (melo)dramatic? And the people who don’t die immediately after getting shot just need to have the bullet removed so that everything is OK. They can go to a back-street doctor or anyone with a pair of rusty pliers, and as soon as the shrapnel is extracted - "He'll be ok!"

Unfortunately TV and movies are NOT reality. Which shouldn't come as a shock to you, but it does to everyone else.

You see, we don’t routinely remove bullets from people who have been shot. After the bullet stops moving (if it's still inside you), it doesn't do anything. It just sits there. If it’s not in the way of anything, there are simply very few reasons to remove it. Digging around for it can damage the surrounding tissues and cause more harm than good. In any case, I haven’t yet got a police request for the bullet to be retrieved from a victim to help find the shooter.

"YOU AREN'T GOING TO REMOVE THE BULLET??"

No, I'm not.

"WHY NOT??!"

I try to explain what I just said above, but the patient still looks at me like I’m crazy.

But don’t get me started now on the TV medical dramas and all the mistaken expectations they foster. That’s a rant for another time.

20 April 2020

Week 4

As a surgeon of the orthopaedic variety, I can safely say that I have not had the need to use a stethoscope much in my usual clinical practice (apart from using it when I can't find a hammer to elicit certain reflexes from patients – unlicensed use). Due to the COVID19 crisis, a lot of us have been deployed to different areas in the hospital (such as the Emergency Department) so I have had to reacquaint myself with the proper use of a stethoscope again. Thankfully I am not alone because in the Emergency Department, I find myself working next to doctors and surgeons of various grades and specialties, and we are all trying to renew our skill sets to deal with the onslaught of patients needing medical care.

The notion that teams are the basic building-blocks of organisations is not new. Recruitment ads routinely call for "team players". Business schools grade their students in part on their performance in group projects. Office managers knock down walls to encourage team building. Teams are as old as civilisation, of course: even Jesus had 12 co-workers.

There is a slightly collegiate feel to the Emergency Department these days. While Addenbrooke's lacks the opulence of St John's, I've swapped casual conversations with my friends from various academic disciplines for conversations of a different kind as physicians and surgeons and the not-very-medical (*cough* dermatologists) share anecdotes and engage each other with our work and our lives. Keeping up with the latest in COVID19 research whilst refreshing our core medical skills, it's helpful to revisit the things we learn early on with the benefit of experience. The challenging cases we see are of course punctuated with the more esoteric ones, such as the patients who present with Objects Inserted and Ingested in Places They Shouldn't Be.

Life in the hospital goes on as usual over the Easter bank holiday, although all the chocolate in the department would shock any high street confectioner! (and elicit a raised eyebrow from the most hardened diabetes specialist doctors) At some point today, the ages of the patients in our department ranged from 2 weeks to 103 years old. The chaos and uncertainty demand an unyielding focus on core medical principles and consistent modelling of professionalism, altruism, quality, and safety. Once our egos and personality differences were put aside, there was a real camaraderie when we worked through the same difficult situations together. As the next breathless or broken patient is about to be wheeled into the resuscitation bay, I am aware that there are high-stakes decisions to be made. I look around and see my colleagues with our different backgrounds and for a moment, I wonder if we are all trying to remember our treatment algorithms and summoning the sage advice from our mentors. And the glint in our eyes shows that we are all ready for the challenge.

Everything you learn is valuable because somehow, sometime, you'll draw upon it to save a life or prevent serious permanent injury. Take care and stay safe.

14 April 2020

Week 3

"Shortcut" is one of my favourite oxymorons. If you ask my friends, they will (correctly) inform you that most of the shortcuts I've found around College/work/gym take longer to get to than most conventional routes. Yet I continue to take the so-called shortcut because somehow in my mind they are better, though not necessarily faster. Damn it, it just has to be better!

Doctors use lots of little written shortcuts and abbreviations when writing in patients' charts. These not only document how the patient is doing, but also communicate our thoughts with other members of staff, which is rather important when it comes to patient care. Like my off-road alternate routes, our shortcuts are designed to save time too, but unfortunately that isn't always the case.

.

As vital as they are, there is just one major problem with trying to read a doctor's note - they are indecipherable. Sure, everyone has heard that old stereotype of doctors and their bad handwriting. As it turns out, there's a very good reason that stereotype exists - because it is completely true. Our handwriting in general is absolutely atrocious. So why do we do it? Obviously it's to prevent lawyers from being able to read them. There are courses in medical school to teach people to write so that it looks like we are holding the pen with our feet (I kid. Sort of.)

Unlike many of my colleagues, I do my best to make sure my handwriting is legible, and about 99% of the time I'm successful. We have electronic patient records in my hospital, but we often have very unwell patients who are transferred from other hospitals in the region and land in the resuscitation room with a stack of paper notes which are basically chicken scratch. It would take the full capabilities of MI5, the CIA and Mossad to translate some of these scribblings. I sometimes can't figure out if my colleague's note says he is going to "repair the tendon" or "replace the television".

Fortunately, hospitals are cracking down on this and as electronic medical records become more widespread, this sort of problem will eventually (hopefully) vanish. Until then, I'll have to continue wondering what on earth ℑℏ℘ℴ⅄↬∯⍭ℴ is supposed to mean. I think it means either "the patient is doing well" or "meet me in the pub at 6pm", but I may have to ask a colleague to translate it for me.

7 April 2020

Week 2

I was chatting with one of my younger colleagues, and it turns out that despite the modern era of evidence-based medicine, people who work in healthcare remain a superstitious lot! I thought it might be interesting for those not in the business to read about some of our superstitions so here goes...

My favourite is the 'Q' word – 'quiet' - it truly is the kiss of death. The 'S' word - 'slow' - carries a similar jinx. Guilty parties are usually newbies who are "not superstitious" (or even worse, patients) who declare, "It's really quiet in here this morning" or "Hope you have a quiet shift!". Everyone within earshot bristles as the Q word invokes the Call Gods*, who take it upon themselves to summon a storm of Gomorrah-like proportions and rain the sickest patients on your hospital doorstep, only relenting when the shift is over.

*the Call Gods watch over all doctors on-call all over the world. They decide what patients will come into hospital, when, and for what reason. You do not mess with the Call Gods.

The Call Gods do not reserve their torture for unsuspecting staff who disavow all knowledge of their existence. No, they seem to enjoy paying attention to me whenever I am on duty, though they can be terribly uninspired when it comes to choosing patients to drop in my lap. For whatever reason, the Call Gods decided that one fine recent day would be Fall Day. Everyone was falling - falling down stairs, falling off ladders, falling out of trees, falling after getting hit. OK, maybe that last one technically doesn't count. Anyway, when I found out I was getting my fifth fall victim of the day, my first thought was, "Bring it on!"

As I approached the patient on the stretcher, they struggled to conceal their bewilderment (and justified scepticism) when I introduced myself as their doctor (having only regularly religiously claimed my student discount from their shop over the last year!)

If you were wondering about other superstitions, many have been studied in varying levels of detail and those worry me less. Friday 13th does not influence the severity of surgical blood loss (Schuld 2011). The full moon has no impact on Emergency Department patient volume or hospital admissions (Thompson 1996; Kamat 2014). Lunar phase also has no apparent correlation with ITU mortality, seizures, childbirth complications, agitation, or kidney stones. (Cohen-Mansfield 1989; Chapman 2000; Arliss 2005; Molaee 2011; Nadeem 2014) However, a full moon might actually be protective against intracranial aneurysm (ballooning of a vessel in the brain due to vessel wall weakness) rupture, except that this is almost certainly just the result of too many studies examining a phenomenon with no effect (Banfield 2017).

Back to you - so what superstitions, if any, do you have?

Arliss JM, Kaplan EN, Galvin SL. The effect of the lunar cycle on frequency of births and birth complications. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005; 192(5):1462-4.

Banfield JC, Abdolell M, Shankar JS. Secular pattern of aneurismal rupture with the lunar cycle and season. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2017; 23(1):60-63.

Chapman S, Morrell S. Barking mad? another lunatic hypothesis bites the dust. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2000; 321(7276):1561-3.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Werner P. Full moon: does it influence agitated nursing home residents? Journal of clinical psychology. 1989; 45(4):611-4.

Kamat S, Maniaci V, Linares MY, Lozano JM. Pediatric psychiatric emergency department visits during a full moon. Pediatric emergency care. 2014; 30(12):875-8.

Molaee Govarchin Ghalae H, Zare S, Choopanloo M, Rahimian R. The lunar cycle: effects of full moon on renal colic. Urology journal. 2011; 8(2):137-40.

Nadeem R, Nadeem A, Madbouly EM, Molnar J, Morrison JL. Effect of the full moon on mortality among patients admitted to the intensive care unit. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2014; 64(2):129-33.

Schuld J, Slotta JE, Schuld S, Kollmar O, Schilling MK, Richter S. Popular belief meets surgical reality: impact of lunar phases, Friday the 13th and zodiac signs on emergency operations and intraoperative blood loss. World journal of surgery. 2011; 35(9):1945-9.

Thompson DA, Adams SL. The full moon and ED patient volumes: unearthing a myth. The American journal of emergency medicine. 1996; 14(2):161-4.

31 March 2020

Week 1

“And there are no more surgeons, urologists, orthopedists, we are only doctors who suddenly become part of a single team…”

Dr Daniele Macchini, Bergamo, Italy (March 2020)

In Addenbrooke’s Hospital, time is of the essence. Managing some of the most unwell patients in the region 24/7 requires a massive amount of organization, dedication and teamwork. Returning to NHS shifts after a stint in PhD research is a shock to the system but I must thank the boat club for keeping me fit, so the relentless hours don’t seem so bad after all!

As COVID-19 continues to challenge healthcare systems globally, I am constantly reassured by the camaraderie of my colleagues in hospital.

But life in John’s remains a source of surprises and joy - I am always inspired by the kindness and positivity of people around me, those who come together because they like something or believe in something, those who want to create positive change, those who work to keep our community connected even in a time of social distancing – and all that helps me do what I do.

There is an overwhelming sense that we are all in this together, and no one must deal with it alone.

27 March 2020