Slavery and Abolition: Collections Uncovered

Introduction

This exhibition for the 2021 Cambridge Festival is a collaboration between St John’s College Library and Wisbech & Fenland Museum. It is not designed as a full history of the 18th and 19th century Atlantic slave trade, and the campaigns to abolish it; nor, even, is it quite intended as an overview. Rather, in presenting a selection of items – a number of them never previously exhibited – from the Library’s and Museum’s collections, and offering, in brief commentary, a necessarily limited version of that history, the curators hope to prompt conversation about the social dynamics of oppression and hypocrisy surrounding the slave trade, and to nod towards the continuing relevance of the issues involved. At the end of the exhibition is a video of a panel discussion responding to some of the material.

Please note that, owing to the topic, much of the material in the exhibition is likely to be distressing. Language today considered racially insensitive was deployed by white slaveowners and white abolitionists alike. And one tactic used by abolitionists was that of confronting people with the often violent realities of slavery: so, alongside the casual attitudes of slaveowners, the exhibition features abolitionists’ verbal and visual accounts of slave ships, floggings, and other abusive behaviour. The material, then, is sometimes unintentionally and sometimes deliberately shocking; the curators’ goal in presenting these primary sources, however, is not to shock.

It should also be stressed that the (sparing) use in the exhibition text of the word ‘slave’ is not intended to reduce any individual person to being defined by their enslaved status; further, references to ‘Africa’ and ‘Africans’ are not intended to homogenise.

Names and reputations

Two names recur in this exhibition. One is that of Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846), who devoted much of his life to campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade, and of slavery in its entirety.

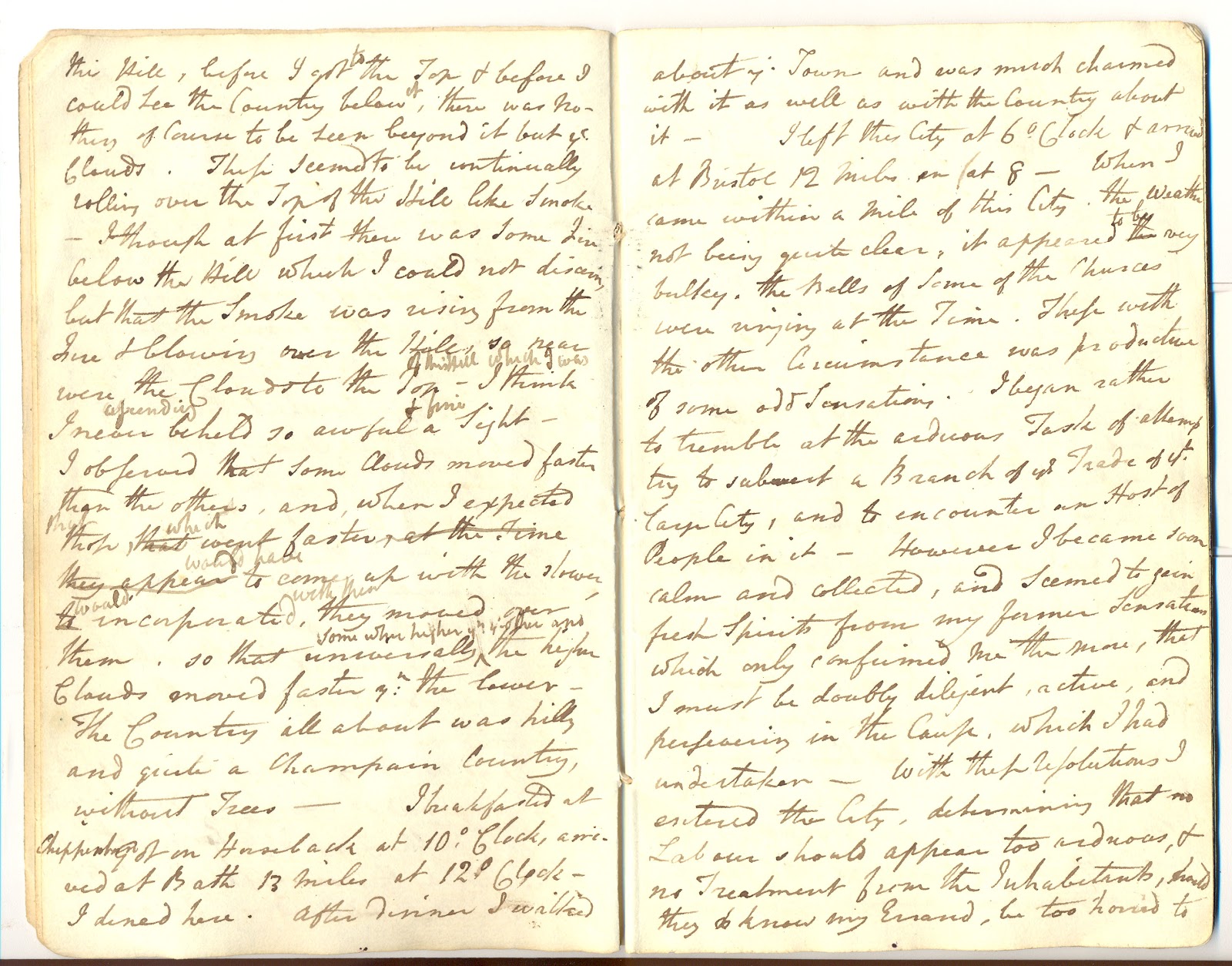

Clarkson came to St John’s College as a student in 1780, and it was in Cambridge that he began to write and publish against the practice of slavery. In 1786 he met William Wilberforce, who went on to lead the campaign for abolition in Parliament; Clarkson’s battle was on the ground, and involved him in extensive travels, for research and public addresses, around the country. He corresponded widely, and wrote twenty-three books and pamphlets, most of them on the subject of slavery. As he was opposing a societal norm – English people had been connected to the slave trade since the 1560s, and the state had officially sponsored its first trade company in 1660 – Clarkson was a controversial figure, and his travels, which through his intense commitment would have exhausted him physically and mentally anyhow, carried additional risks: for example, an attempt was once made to drown him in Liverpool. In his diary of 1787, many entries begin with him setting off yet again on horseback, on foot, or by boat.

Pictured above is an entry that mentions his arrival in Bristol, a major hub of the trade. Clarkson discovered there that sailors of all ethnicities were poorly treated, and that many had been tricked into debt bondage and forcibly recruited.

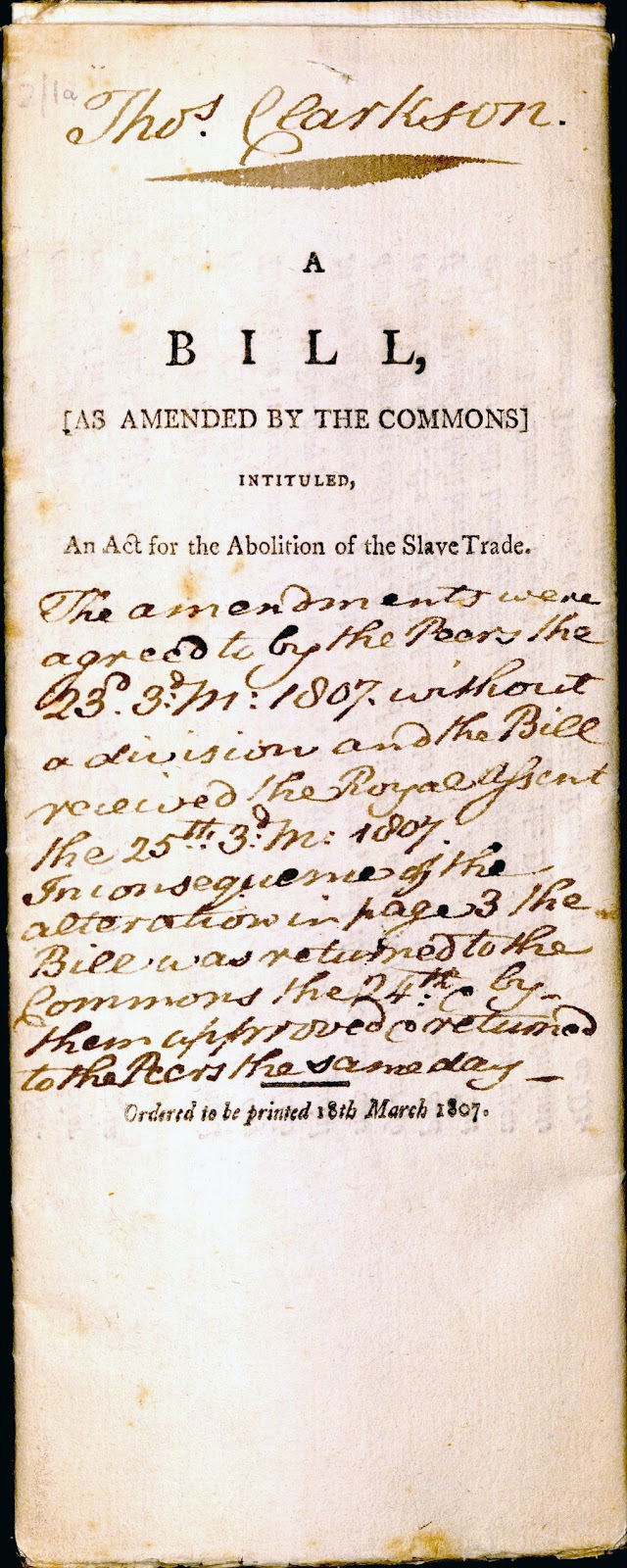

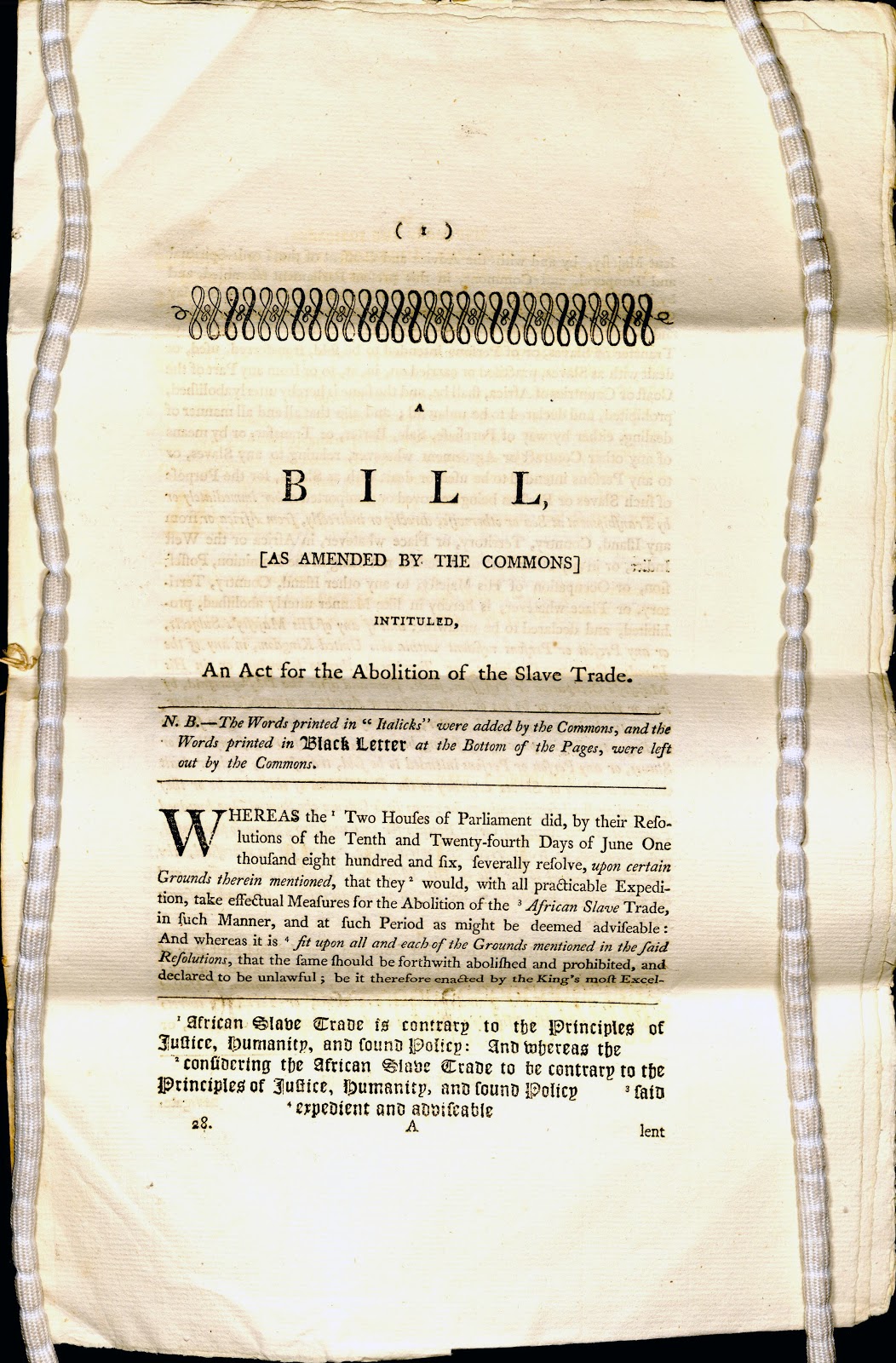

Great Britain illegalised trading in slaves in 1807, thanks in part to the work of Clarkson and other abolitionists. The collection at St John’s includes Clarkson’s annotated copy of the Bill, titled An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Another Johnian, the poet William Wordsworth, was moved to dedicate a sonnet to Clarkson. It is pictured here in an 1849 edition of Wordsworth’s poems.

Clarkson! it was an obstinate hill to climb:

How toilsome – nay. how dire – it was, by thee

Is known; by none, perhaps, so feelingly;

But thou, who, starting in thy fervent prime,

Didst first lead forth this pilgrimage sublime,

Hast heard the constant Voice its charge repeat,

Which, out of thy young heart's oracular seat,

First roused thee.—O true yoke-fellow of Time,

With unabating effort, see, the palm

Is won, and by all Nations shall be worn!

The blood-stained Writing is for ever torn,

And Thou henceforth wilt have a good man's calm,

A great man's happiness; thy zeal shall find

Repose at length, firm friend of human kind!

Wordsworth's effusiveness should be balanced with the acknowledgement that, with two centuries of retrospect, Clarkson, Wilberforce and others were not necessarily above reproach in every thought they had with respect to slavery, and to the structures that enabled it. One can look at their achievements without placing them upon pedestals.

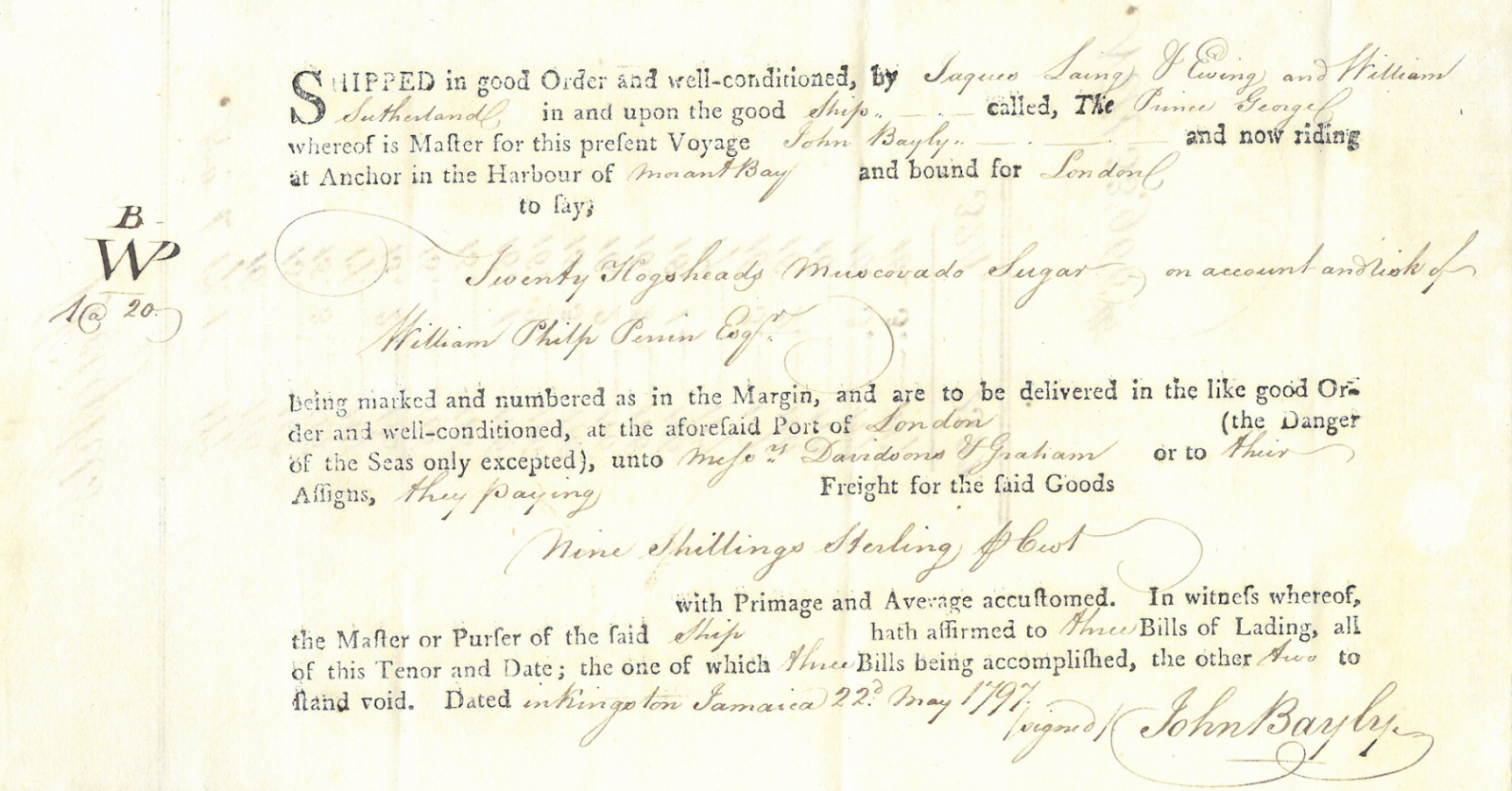

Another key name is a less famous one: William Philp Perrin (1742-1820). Perrin lived in England and inherited his father’s Jamaican sugar plantations; as was then standard, these plantations were laboured on by enslaved Africans, and thus Perrin became a slaveowner. The Old Library of St John’s has acquired a few batches of Perrin’s correspondence, the bulk of it in the last couple of years. While there is little material by Perrin himself, the nearly two hundred letters from attorneys, importers and property managers reveal much about the day-to-day economics, over several decades, of the plantations. And amid much talk of finances, the quality of produce, the weather, and shipping details – several (duplicate) bills of lading, such as that pictured below, are included, having been sent to Perrin for his records – there are a great many references to slaves and the attitudes taken towards them, both before and after the trade’s abolition in 1807.

Perrin’s nephew, Sir Henry Fitzherbert, inherited the estates in turn in 1820. It is important that St John’s acknowledge that Fitzherbert was a Johnian as much as were the more sympathetic figures named earlier (although we have found no record of the family donating money to the College) . A thread that runs through the exhibition is that of the quotidian nature of the slave trade and slave ownership: this was not some esoteric evil happening off to the side, but an everyday part of life for a great many people who certainly did not consider themselves evil or even unusual. Plantations such as Perrin’s shipped sugar and rum to Bristol, to London and elsewhere; people paid money to consume these products, and so there was a cultural mandate to maintain the systems of production. The task faced by the abolitionists was the task faced by social justice campaigners today: not merely to object to specific practices, but to alter the prejudices and blind spots from which such practices arose and arise.

Confronting the facts

In 1785, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, Peter Peckard, set a topic for the Members’ Prize for a Latin Essay. Peckard had preached a sermon against slavery in the University church, Great St Mary’s, and the question he set for the Prize was ‘Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare?’: ‘Is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?’ Clarkson won the Prize, and his entry was published in English in 1788 as An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. This established the course of his life’s work.

Another 1788 Clarkson publication was his Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade. More will be said later about this work, which inspired Wilberforce’s speech to Parliament on 13 May 1789.

Speaking for three and a half hours at the commencement of an eighteen-year campaign against the slave trade, Wilberforce concluded with twelve resolutions. His focus was upon the trade, not upon slavery per se, but there might have been some wisdom in breaking up a seemingly impossible end goal into more achievable aims.

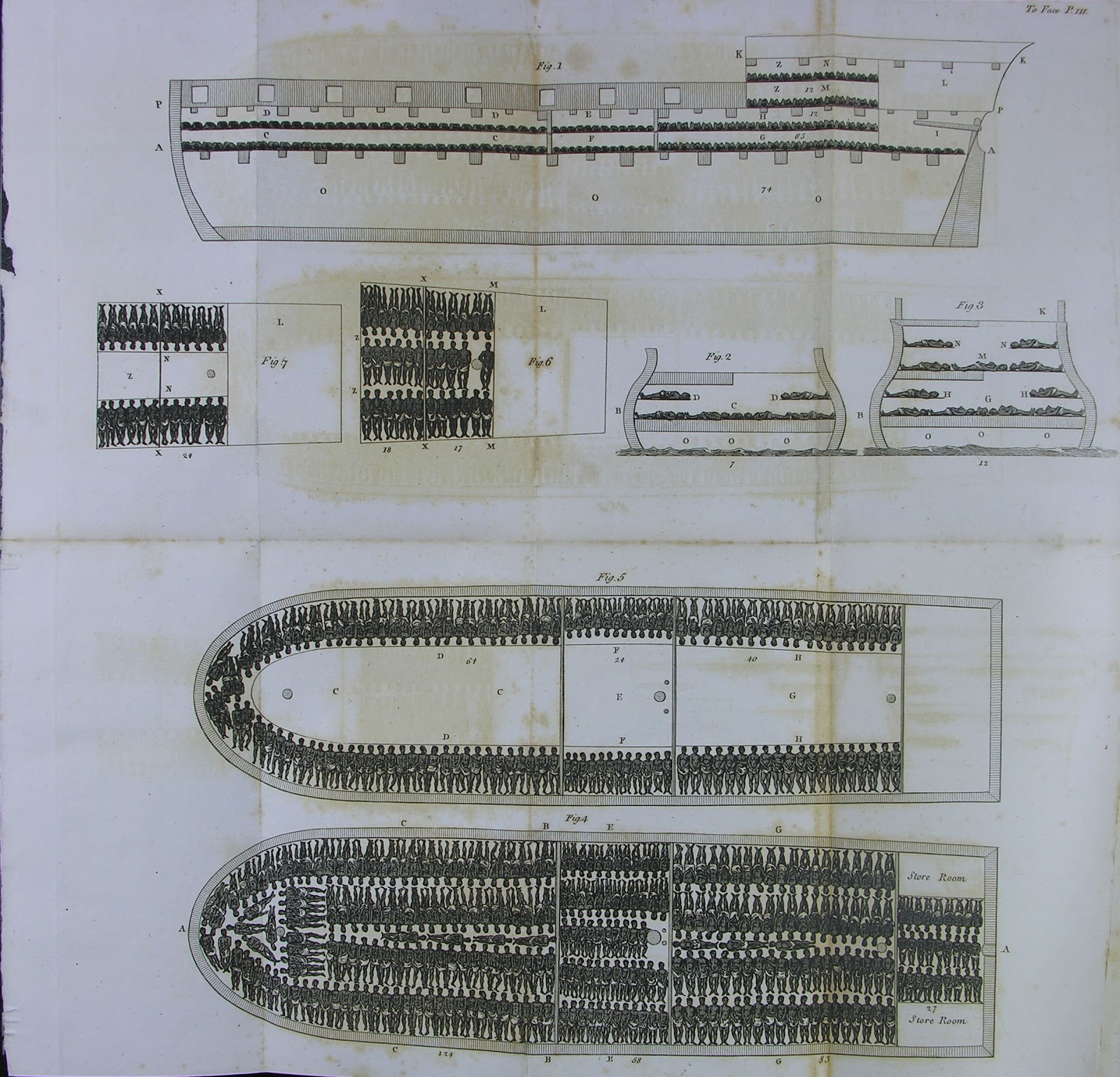

And the abolition of the trade must have seemed a worthy aspiration in itself. In The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament (1808), Clarkson includes cross-section images of a slave ship. This exemplifies one way in which abolitionists forced people to admit to the immorality of the trade: removing it from the distantly, abstractly philosophical, and putting it in terms of objective fact.

Those transported on such ships were shackled in tight, cramped conditions for weeks or months; they were unable even to stand upright, the deck being only a few feet overhead.

Clarkson also commissioned two scale models of the Brookes, a slave ship, one of which Wilberforce showed in Parliament. Pictured above is a 2007 reproduction.

In Clarkson’s Letters on the Slave-Trade (1791), the selection of his correspondence is accompanied by illustrations, including depictions of the methods used in the binding of enslaved people for transportation on land.

Of course, the end of an enslaved person's transportation did not mean the conclusion of their suffering. And when the trade was abolished, campaigners in Great Britain widened their focus to include slavery proper.

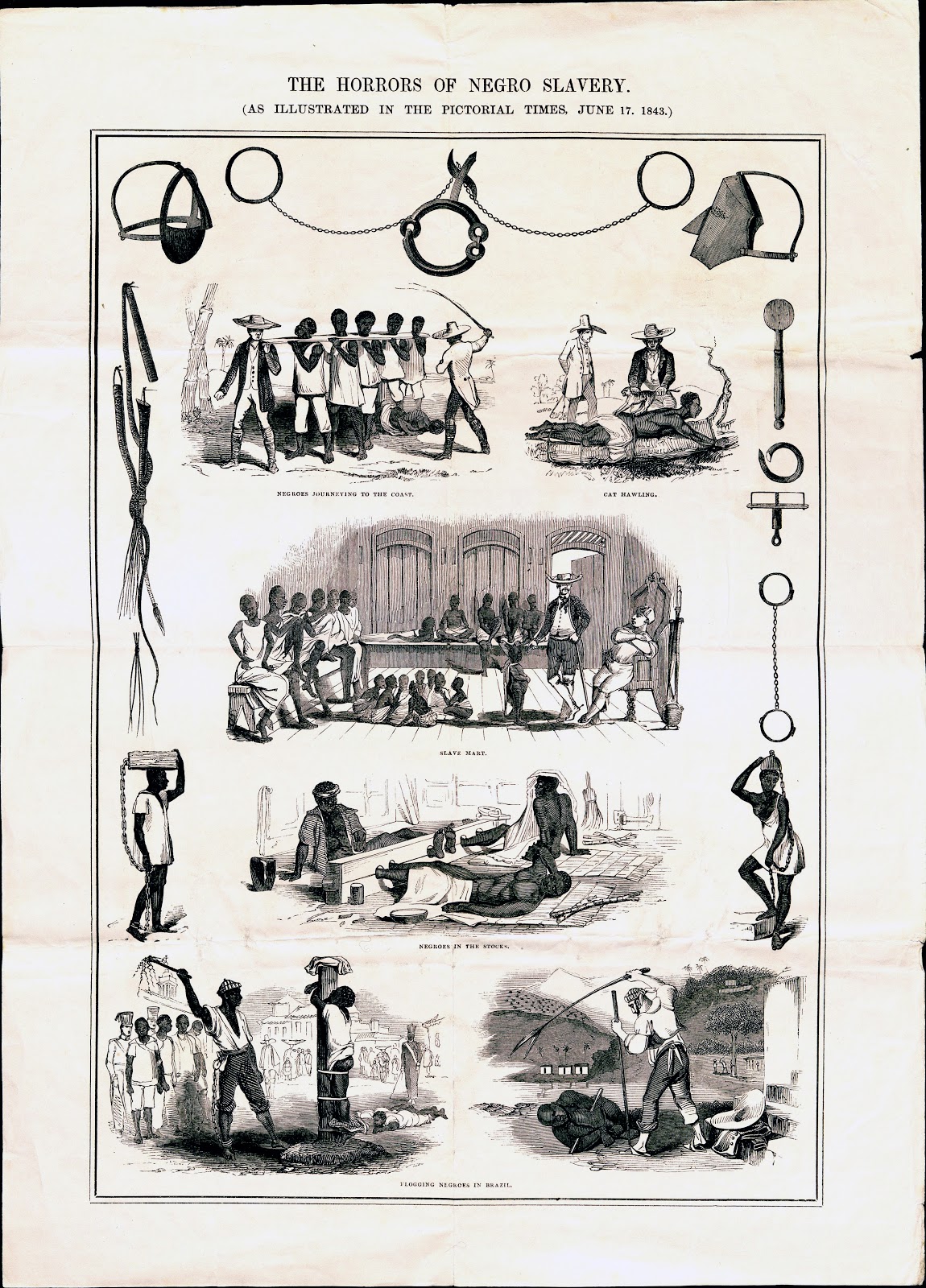

The Pictorial Times’s depiction of ‘The Horrors of Negro Slavery’ (17 June 1843) is an example of the uncompromising visuals employed in the service of the cause, and includes an image of flogging in Brazil, where slavery continued until 1888.

James Montgomery’s four-part poem The Abolition of the Slave Trade (1814) – featuring engravings of pictures by Robert Smirke – deploys, as seen below, the persuasively memorable clinching of rhyming couplets in its appeal to the reader’s sympathies.

And Henry Whiteley’s Three Months in Jamaica in 1832 offers the author’s harrowing eyewitness accounts of the cruel treatment of plantation workers.

In the following passage, Whiteley describes in disturbing detail a pen-keeper’s punishment for letting a mule go astray.

At the command of the overseer he proceeded to strip off part of his clothes, and laid himself flat on his belly, his back and buttocks being uncovered. One of the drivers then commenced flogging him with the cart-whip. This whip is about ten feet long, with a short stout handle, and is an instrument of terrible power. It is whirled by the operator round his head, and then brought down with a rapid motion of the arm upon the recumbent victim, causing the blood to spring at every stroke. When I saw this spectacle, now for the first time exhibited before my eyes, with all its revolting accompaniments, and saw the degraded and mangled victim writhing and groaning under the infliction, I felt horror-struck. I trembled, and turned sick: but being determined to see the whole to an end, I kept my station at the window. The sufferer, writhing like a wounded worm, every time the lash cut across his body, cried out 'Lord! Lord! Lord!' When he had received about twenty lashes, the driver stopped to pull up the poor man’s shirt (or rather smock frock), which had worked down upon his galled posterior. The sufferer then cried, 'Think me no man? think me no man?' By that exclamation I understood him to say, 'Think you I have not the feelings of a man?' The flogging was instantly recommenced and continued; the negro continuing to cry 'Lord! Lord! Lord!' till thirty-nine lashes had been inflicted. When the man rose up from the ground, I perceived the blood oozing out from the lacerated and tumified parts where he had been flogged; and he appeared greatly exhausted. But he was instantly ordered off to his usual occupation.

Whiteley notes later that thirty-nine lashes was the legal maximum, and that he once witnessed fifty being delivered to a woman accused of stealing a hen. Somebody else is punished for visiting a Methodist chapel.

He also has the opportunity to interview enslaved people about their treatment, and the pamphlet is valuable for containing such testimony.

On putting the question to an aged negro, who had formerly been employed to take care of the sheep, but was now in the stable, he said he had been flogged many a time. 'And what were you flogged for?' I enquired. 'When sheep go stray – when sheep sick – when sheep die – then,' said he, 'Busha put me down and flog me till me bleed.' 'And how many lashes,' I asked, 'did Busha ever give you?' 'Ah! Massa,' said the poor old man, 'when me down na ground, and dey flog me till me bleed, me someting else to do den for count de lashes.' This same man, as he was saddling my horse on the day I finally left the estate, made a remark that struck me. 'Now, Massa,' said he, 'you see how poor negro be ’pressed (oppressed). We no mind de work – but dey ’press us too too bad.'

It is little wonder that enslaved Africans often rebelled. The most successful of these attempts was the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), in which enslaved people in Haiti overturned French rule and gained independence. But the Perrin papers occasionally make reference to attempted, failed uprisings in Jamaica, and Wisbech & Fenland Museum have recorded sixty-three rebellions and conspiracies that occurred across plantations between 1789 and 1815. Even when not achieving their aims outright, these rebellions were significant in making slavery a difficult system to maintain.

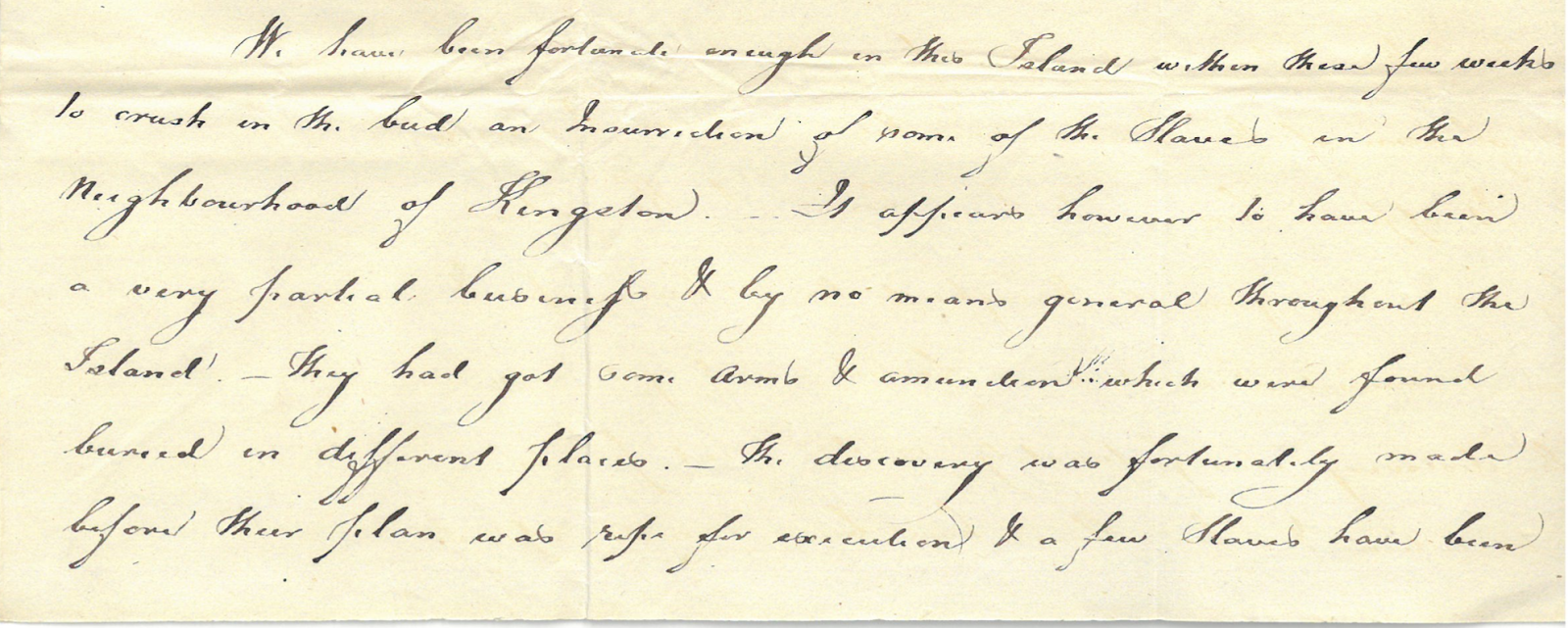

In a letter of 29 June 1803 (Slavery/8/98), property manager William Sutherland (after giving updates on the estates’ output) refers to recent unrest, but suggests that official accounts might be inaccurate.

We have been fortunate enough on this Island within these few weeks to crush in the bud an Insurrection of some of the Slaves in the Neighbourhood of Kingston. It appears however to have been a very partial business & by no means general throughout the Island. They had got some arms & ammunition which were found buried in different places. The discovery was fortunately made before their plan was ripe for execution & a few Slaves have been taken up tryed & executed so that we have no doubt but the business is completely crushed. As matters of this sort are generally much exaggerated I have therefore just mentioned it to you as it really is.

Is Sutherland being entirely honest, or is he understating matters in order to put Perrin’s mind at ease? The latter might not have been necessary: there is little indication in the correspondence that Perrin’s slaves were particularly rebellious. On the other hand, property managers would have had an interest in not reporting every item of bad news.

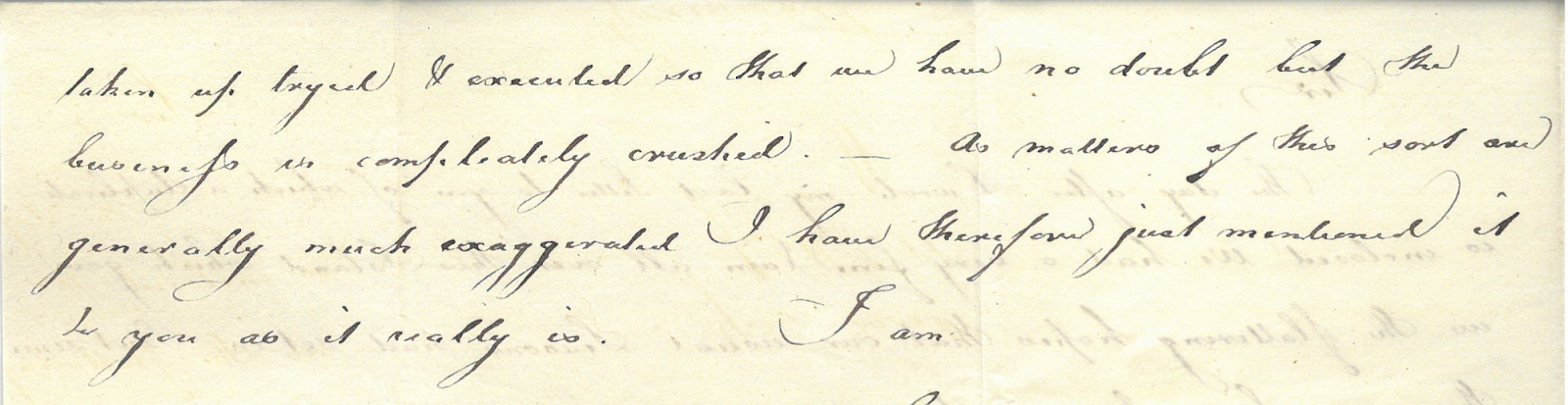

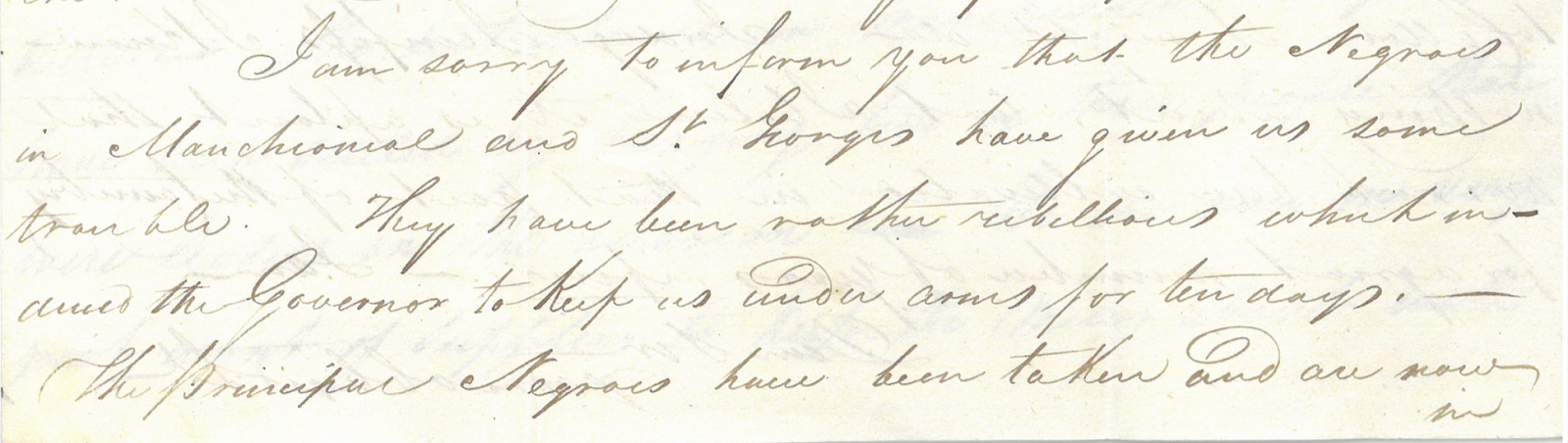

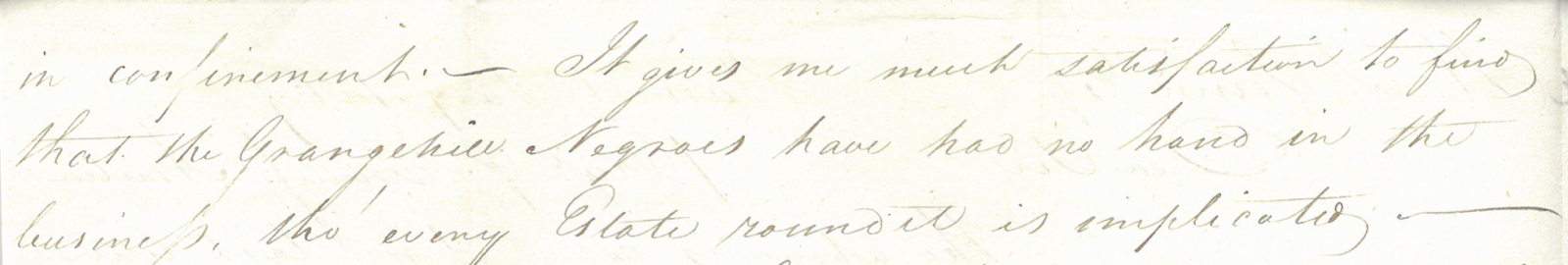

The apparent belief was that enslaved people on Perrin’s estates were treated better than they were elsewhere; one might imagine that Perrin’s paid employees took, therefore, a dim view of the managers of other estates whose treatment of slaves encouraged unrest. Writing on 10 January 1807 (Slavery/8/123), Sutherland’s successor Francis Graham appears to take some pride in the fact that nobody from Perrin’s estates was involved in a recent uprising.

I am sorry to inform you that the Negroes in Manchioneal and St Georges have given us some trouble. They have been rather rebellious which induced the Governor to keep us under arms for ten days. The principal Negroes have been taken and are now in confinement. It gives me much satisfaction to find that the Grangehill Negroes have had no hand in the business, tho’ every Estate round it is implicated.

It was, of course, in the interest of the plantations to discourage such ‘business’ one way or another, by making rebellion seem more trouble than it was worth. Evidently, however, neither the enslaved nor those campaigning on their behalf could be entirely dissuaded.

An economic reality

When an act is abhorrent, it is tempting to think of the person who commits that act as similarly abhorrent, gratuitously and consciously: being fully informed as to the horrors of what they are doing, they do it anyway. This is often not quite the case. The banal fact is that the slave trade was not randomised sadism (although it contained plenty, as has been seen) or a cruelly eccentric pastime, but a huge commercial operation. Plantation owners deployed slave labour not as a matter of personal preference but because they were running businesses and that was how such businesses were run, and how livings were earned. The triangular trade system employed manufacturers, ship crews, insurers and bankers; profits were made on the import and sale of sugar, tobacco and rum. The abolitionists' challenge was to the fundamentals of a socio-economic system.

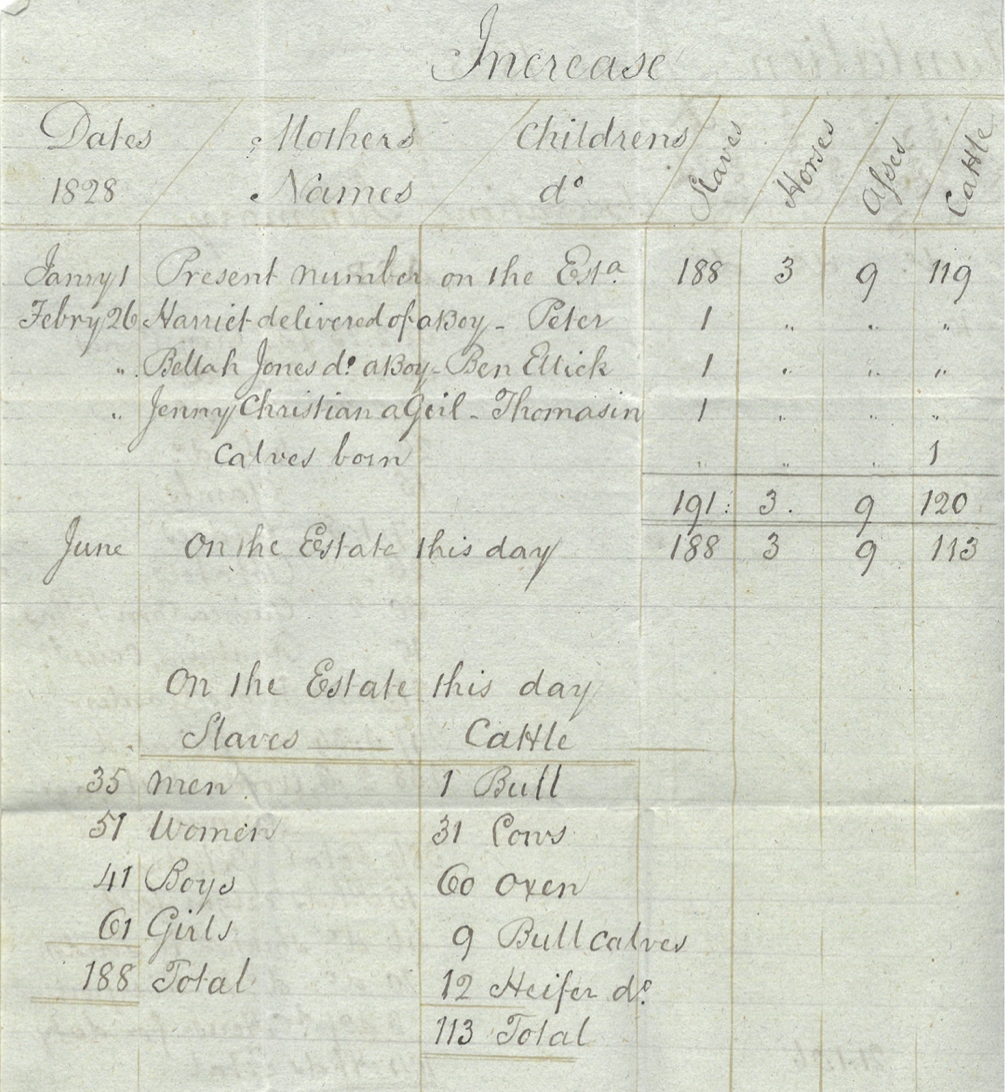

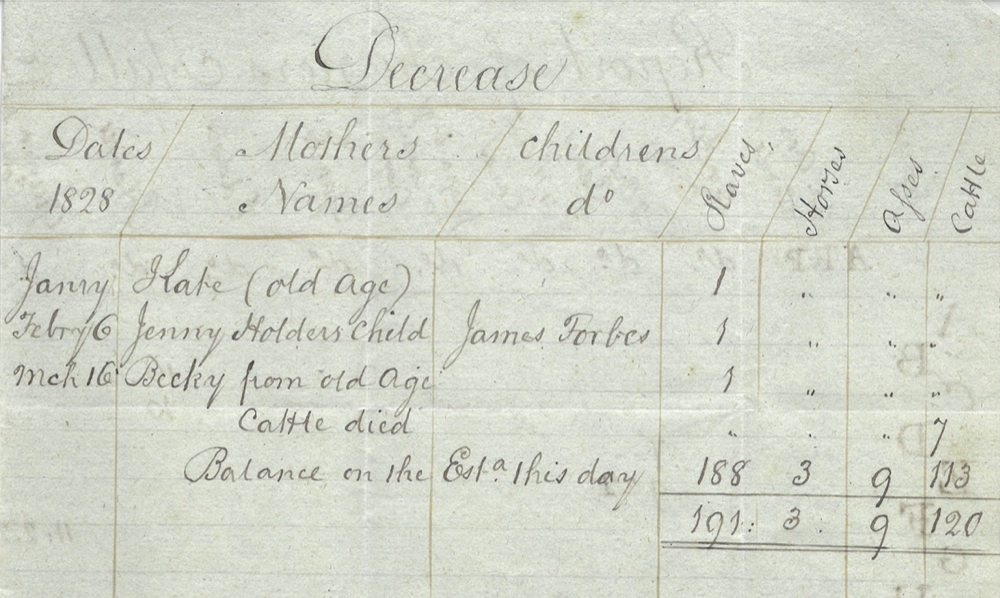

In the above images from a June 1828 account of the Turner’s Hall plantation, slaves are listed alongside livestock as components of the running of a plantation. The increase and decrease in the different populations are recorded.

This is the title page, and the facing fold-out map, from a 1705 edition of Willem Bosman’s A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, originally written in Dutch. Slavery was at the time of publication relatively uncontroversial among white Europeans: trading in slaves was as ordinary as trading in gold or in ivory (perceptions of which have also changed in the centuries since).

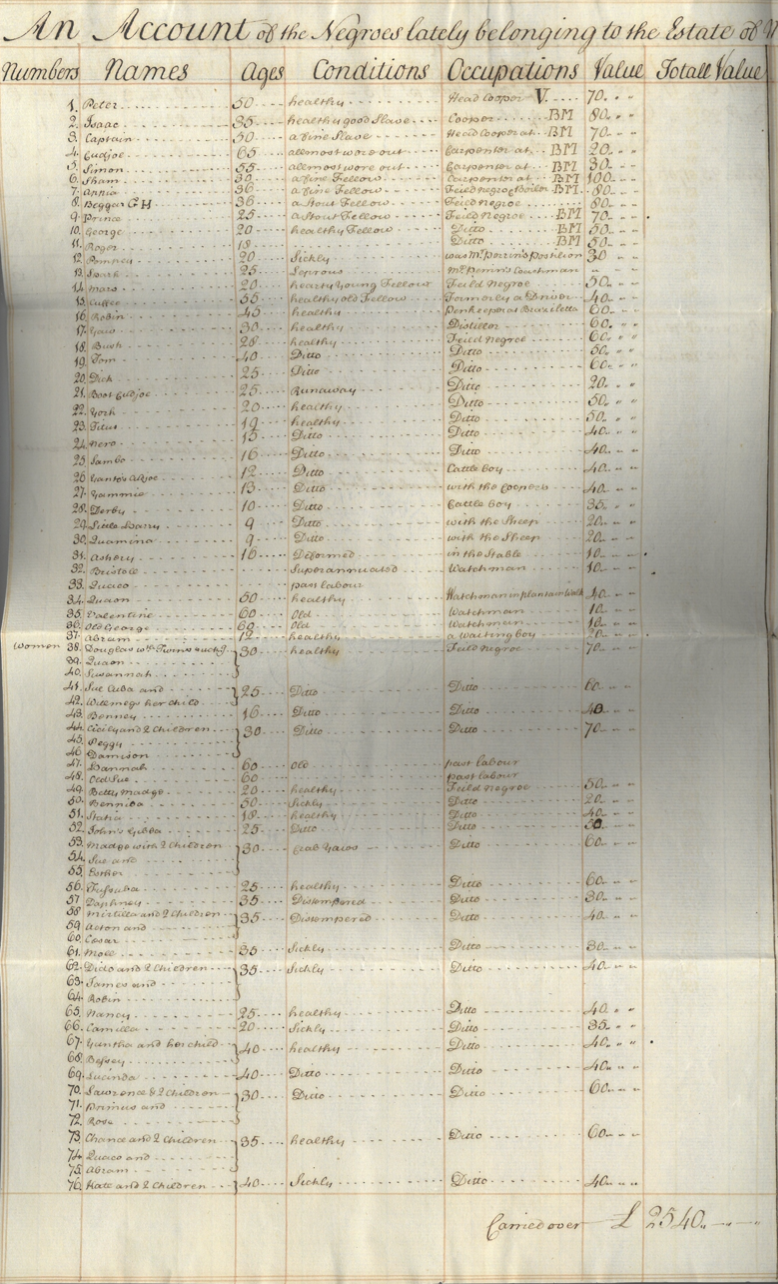

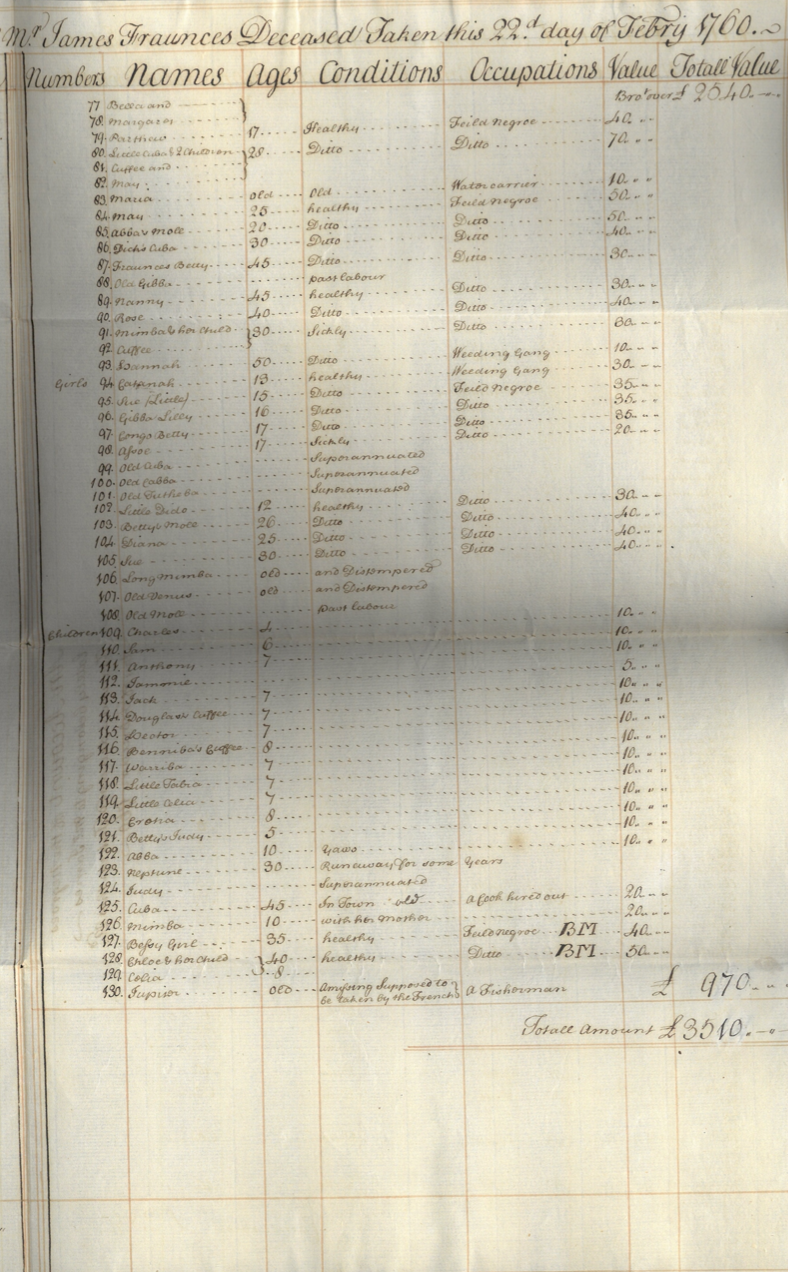

The following list from 22 February 1760 of the slaves of ‘Mr James Fraunces, deceased’ gives the names and roles of one hundred and thirty people, along with a valuation of each. The total value is £3510, whose equivalent in 2021 would be a little shy of £360,000.

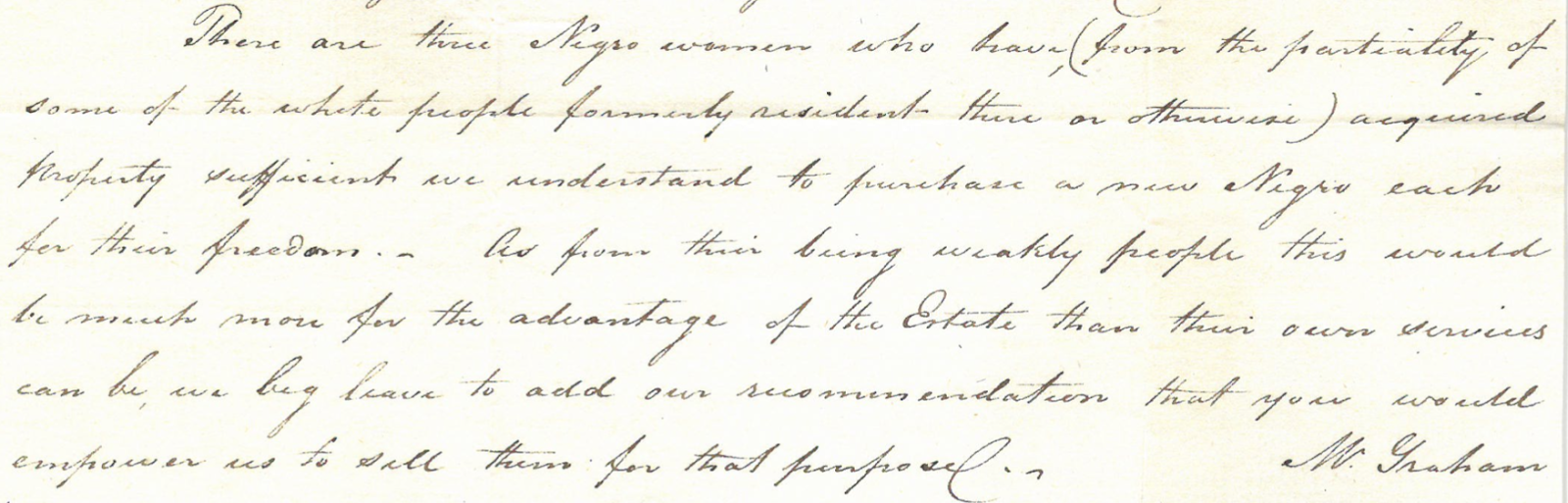

The firm of Jaques, Laing & Ewing, and permutations thereof, handled many of Perrin’s affairs in Jamaica. Included in their letter of 31 August 1805 is the sort of cost-benefit analysis that was involved even with regard to small numbers of the enslaved workforce.

There are three Negro women who have (from the partiality of some of the white people formerly resident there or otherwise) acquired property sufficient we understand to purchase a new Negro each for their freedom. As from their being weakly people this would be much more for the advantage of the Estate than their own services can be, we beg leave to add our recommendation that you would empower us to sell them for that purpose.

The freeing of specific slaves was acceptable, if the price was right.

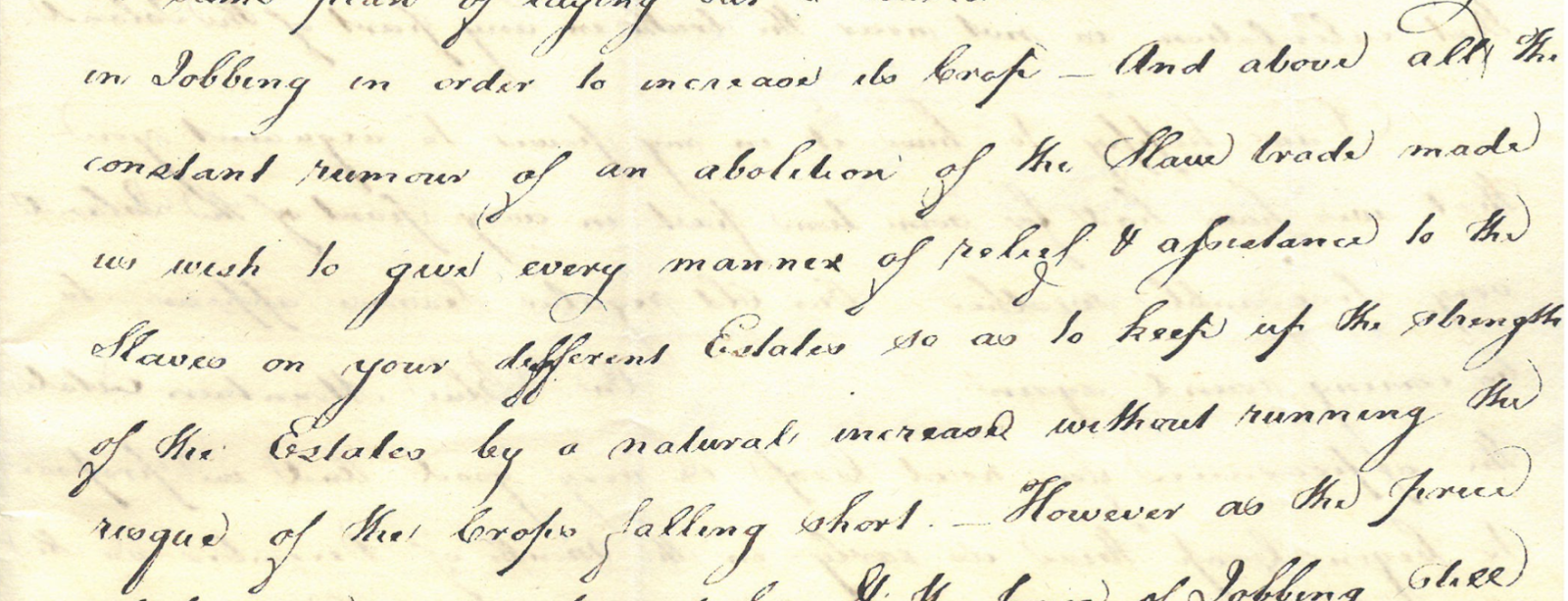

As the abolition of the Atlantic trade approached, Perrin’s managers found themselves in the position not of having to reassess their ethical stance, but of having to think about how to keep the estates running effectively when slave labour became harder to come by. In a letter of 18 October 1800, William Sutherland explains why so much additional money has lately been spent on estate infrastructure; citing first the high prices being fetched by sugar and rum, and competition with other businesses that are engaging in similar investments, he adds the following.

And above all the constant rumour of an abolition of the Slave trade made us wish to give every manner of relief & assistance to the Slaves on your different Estates so as to keep up the strength of the Estates by a natural increase without running the risque of the Crops falling short.

Sutherland perceives that encouraging slaves to have children will become, with abolition, a necessity. Much as one would with livestock, he talks about keeping the slaves healthy so that they will have healthy offspring, marked for slavery in their turn.

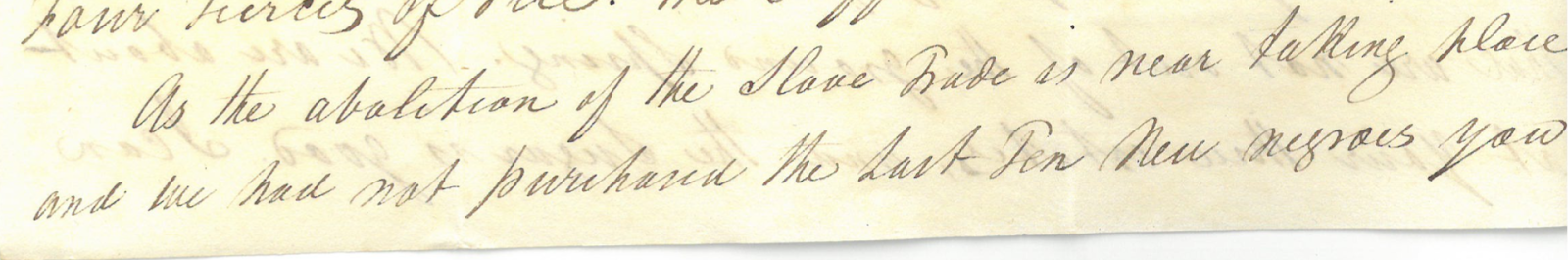

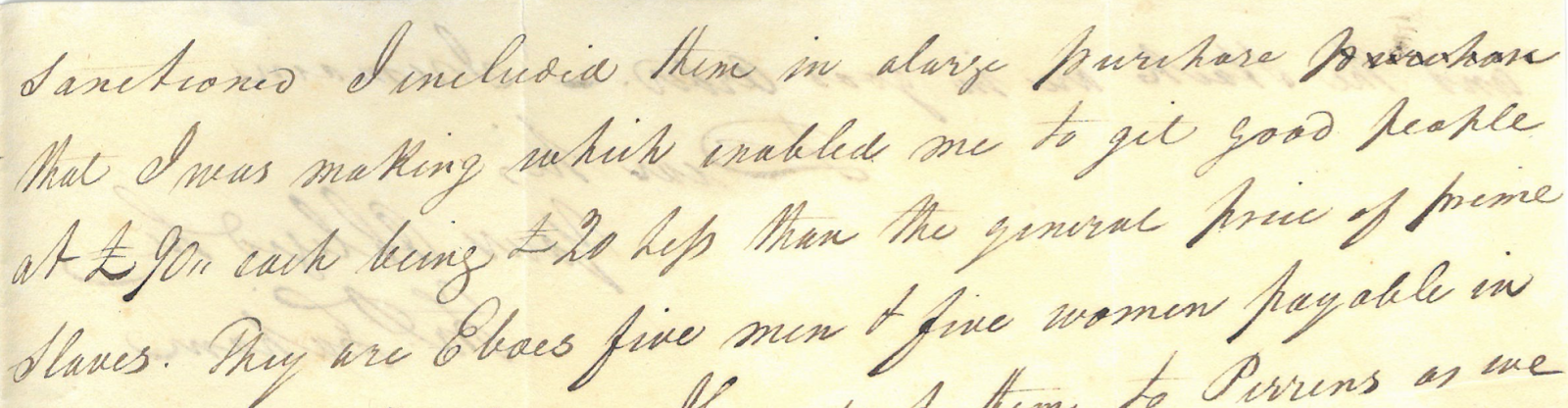

Great Britain made trade in slaves illegal on 1 May 1807, although trade amongst British concerns within the Caribbean continued regardless for four years or so. In a letter of 10 December 1807, Francis Graham takes an entirely practical approach to the impact of the change in the law, having found the opportunity for a bulk purchase and discount.

As the abolition of the Slave Trade is near taking place and we had not purchased the last Ten New negroes you sanctioned I included them in a large purchase that I was making which enabled me to git good people at £90 each being £20 less than the general price of prime Slaves.

Once those enslaved in the West Indies were emancipated in 1833, there began the process of compensating their former owners financially. In 1836, Perrin’s heir Henry Fitzherbert – whose workforce of 981 enslaved Africans was spread across four plantations in Jamaica and one in Barbados – received compensation totalling the equivalent of almost £2.3 million.

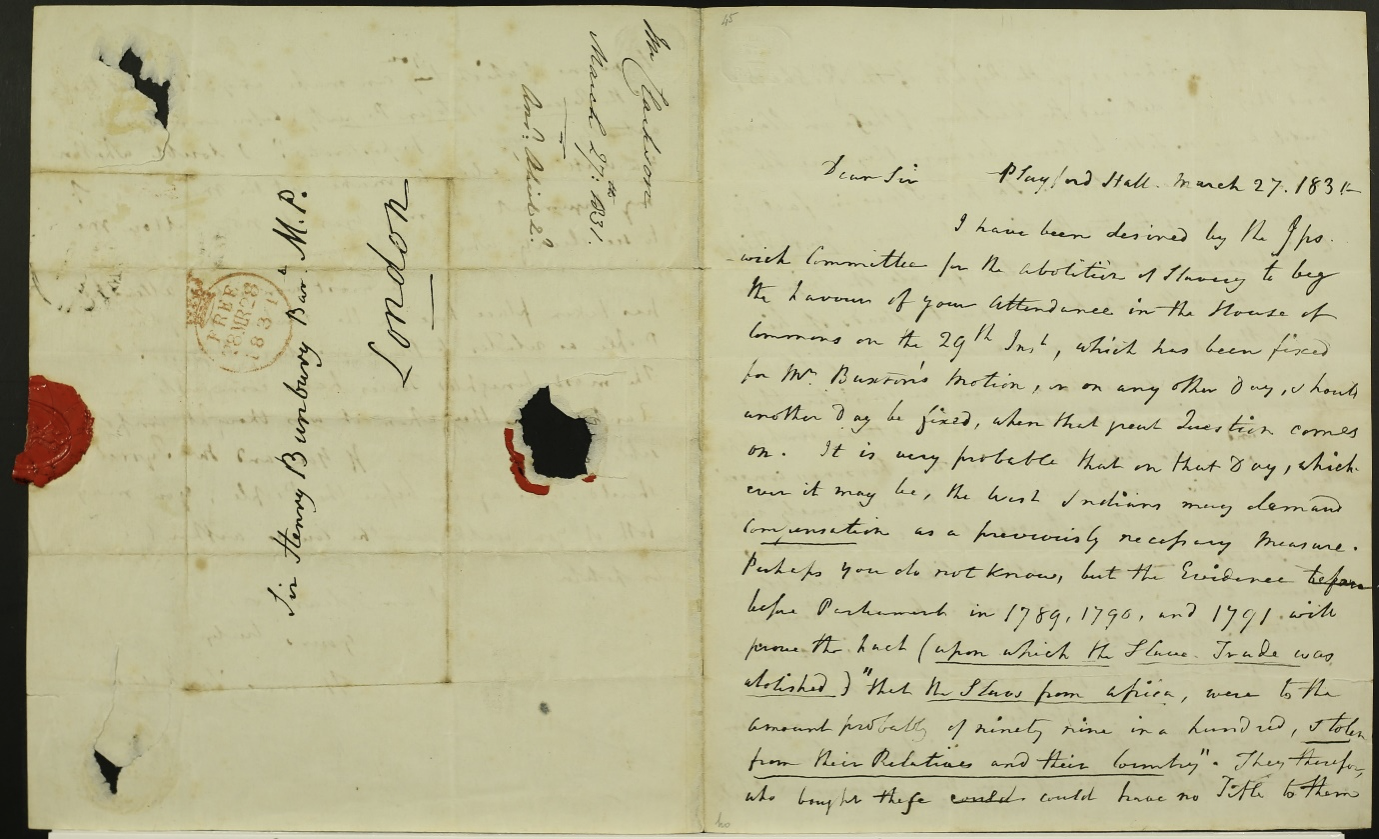

On 27 March 1831, Clarkson wrote the above letter to his MP, Sir Henry Bunbury, lobbying against this system of compensation before it came into effect.

The poor Slave in fact is the only one of the two Parties, who has a just Right to Compensation, a Compensation for all the Injuries done to himself, and heaped upon the Heads of his Forefathers for more than one hundred and fifty years.

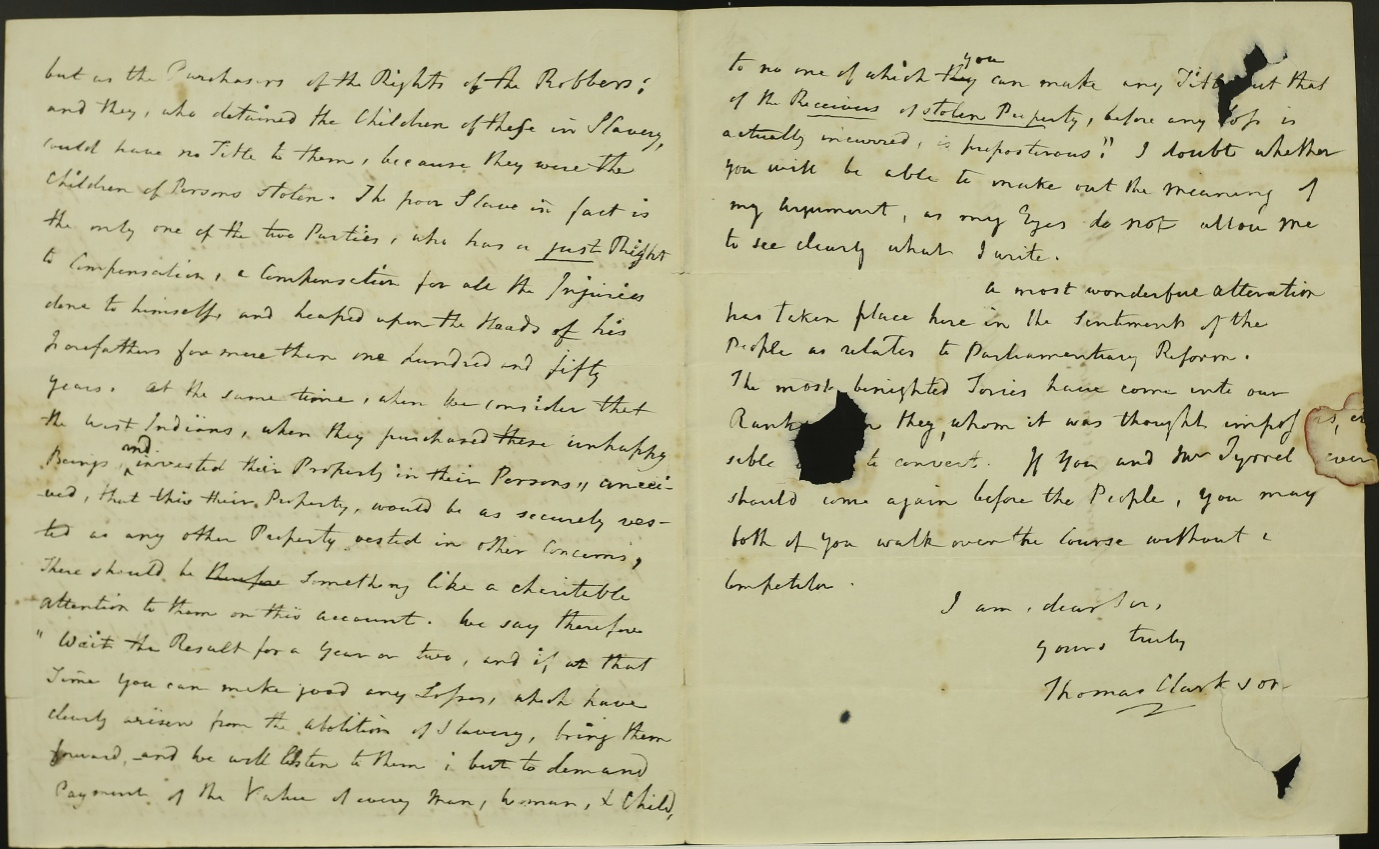

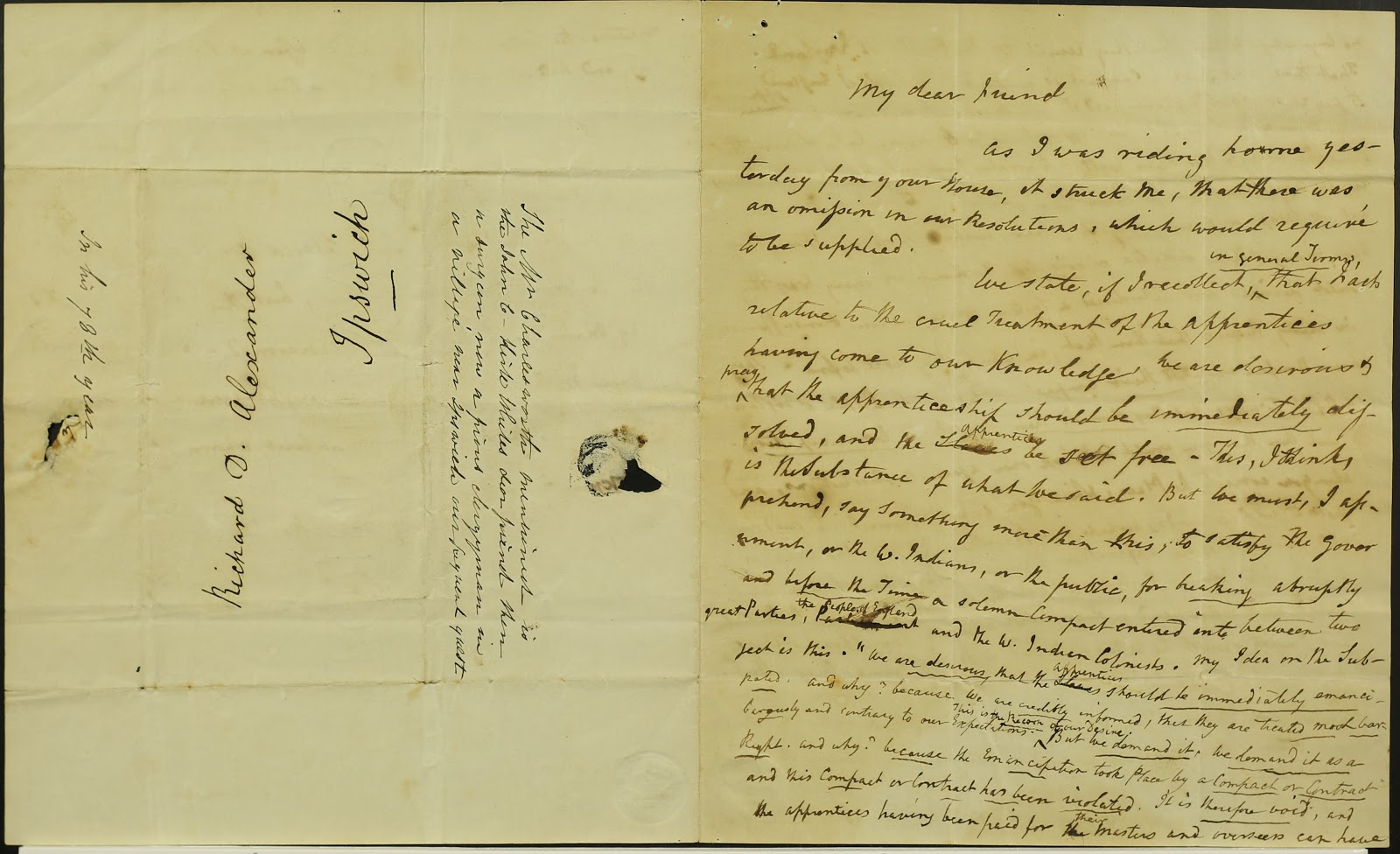

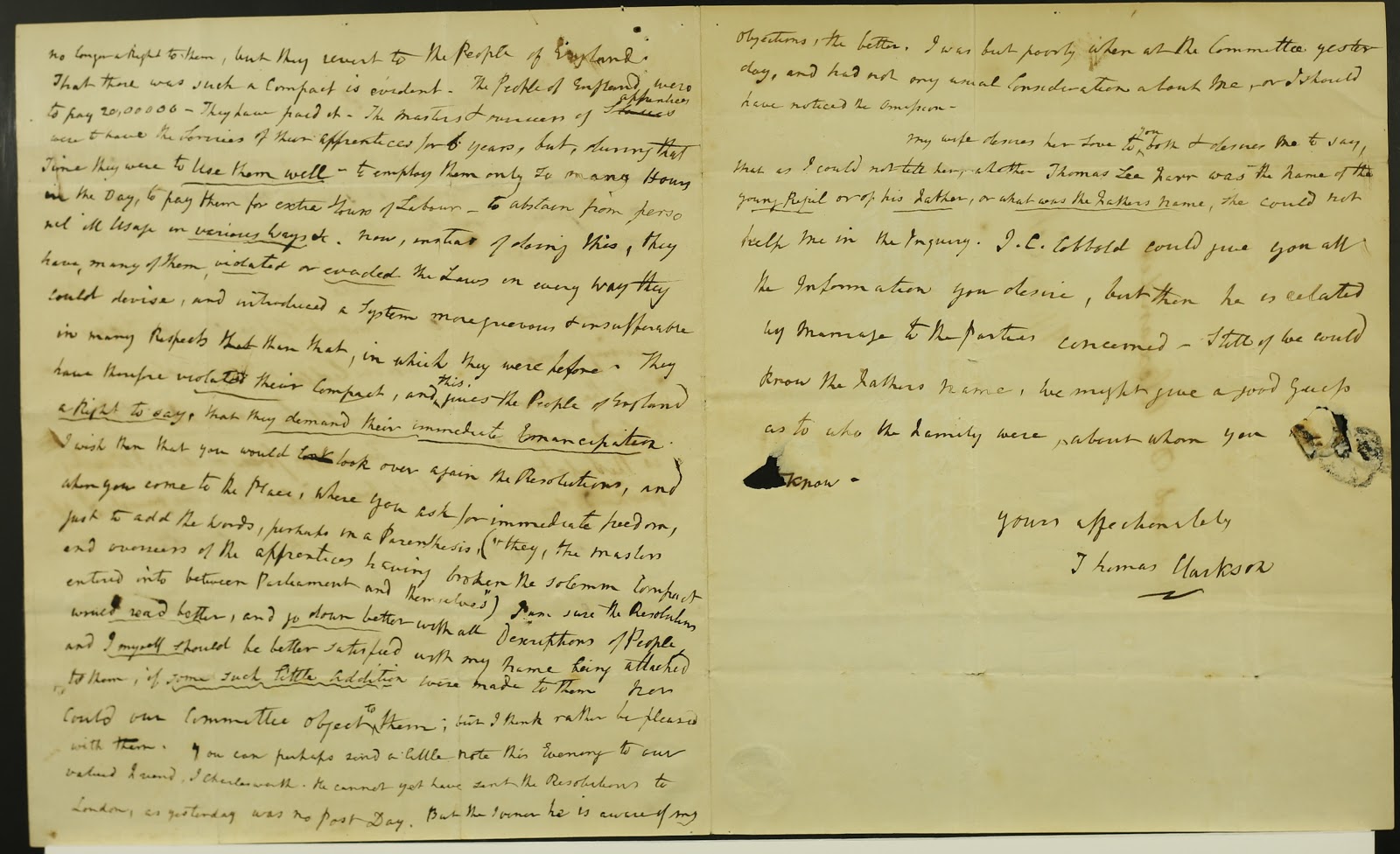

Reparations to slaveowners proceeded, and emancipation was not total: it came with the condition of ‘apprenticeship’, whereby freed slaves were expected to perform six years of further unpaid work for their masters. As recounted in the below letter of 1837-38, written to Richard Alexander, Clarkson and his fellow campaigners learned that apprentices were being treated ‘barbarously’; he insisted that the system must be ‘dissolv’d’.

And why? Because the Emancipation took place by a Compact or Contract and this Compact or Contract has been violated. It is therefore void, and the apprentices having been paid for their Masters and overseers can have no longer a Right to them,, but they revert to the People of England. The People of England were to pay [£]20,000,00[0]. They have paid it.

In today’s money, almost £2.3 billion in reparations had been paid to slaveowners. Clarkson argued that the people of England had effectively bought the enslaved people’s freedom, and must now insist that it be delivered. In 1838, the apprenticeships were brought to an early end.

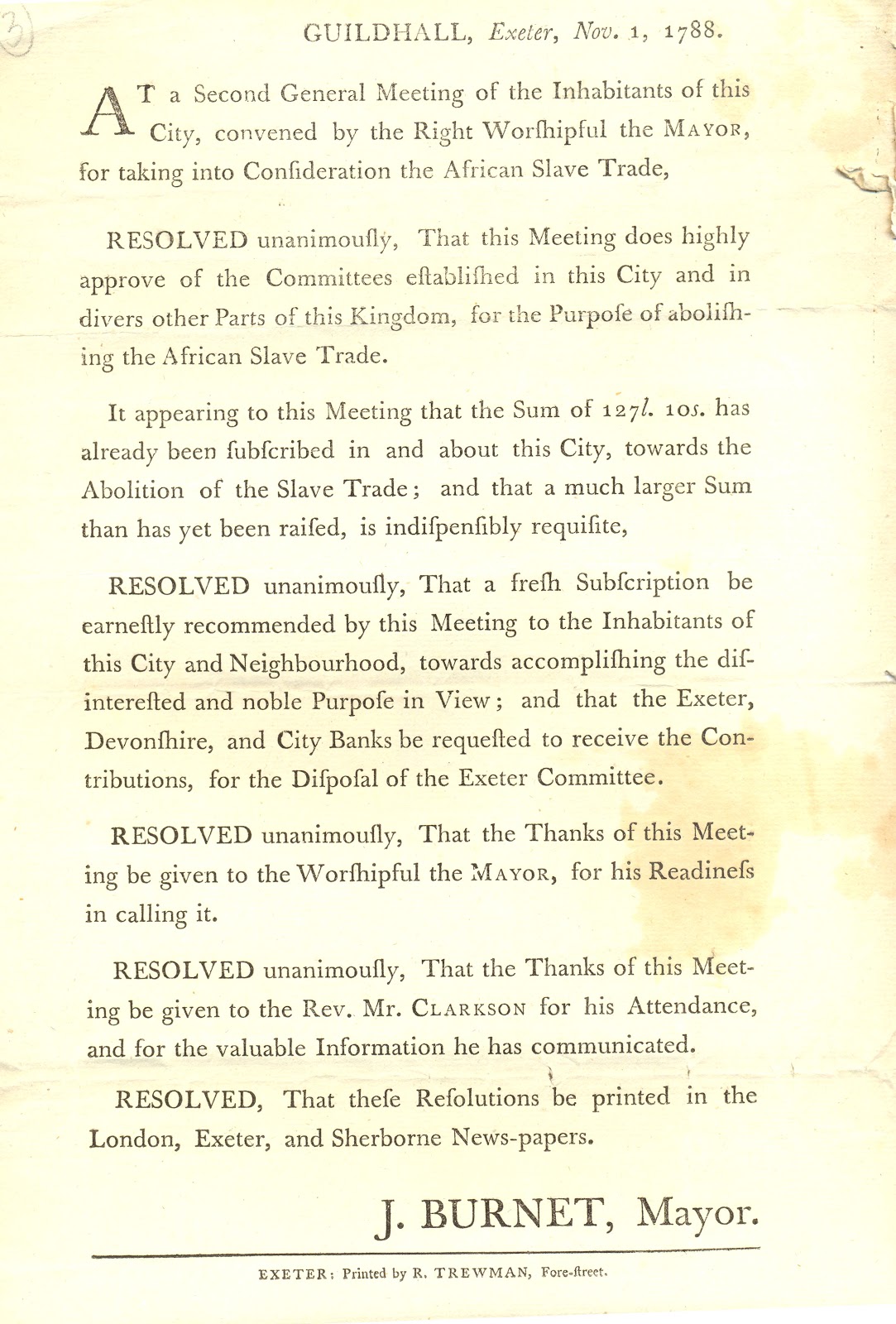

Abolitionists, of course, needed money too. Campaigning required travel, printed material, and time. This handbill from 1788 describes the resolutions of the ‘Second General Meeting of the Inhabitants of Exeter’, called by the city’s mayor for ‘taking into Consideration the African Slave Trade’.

Clarkson spoke at this event; he and other campaigners made appearances at similar meetings around the country, encouraging the establishment of committees and the payment of subscriptions to the cause.

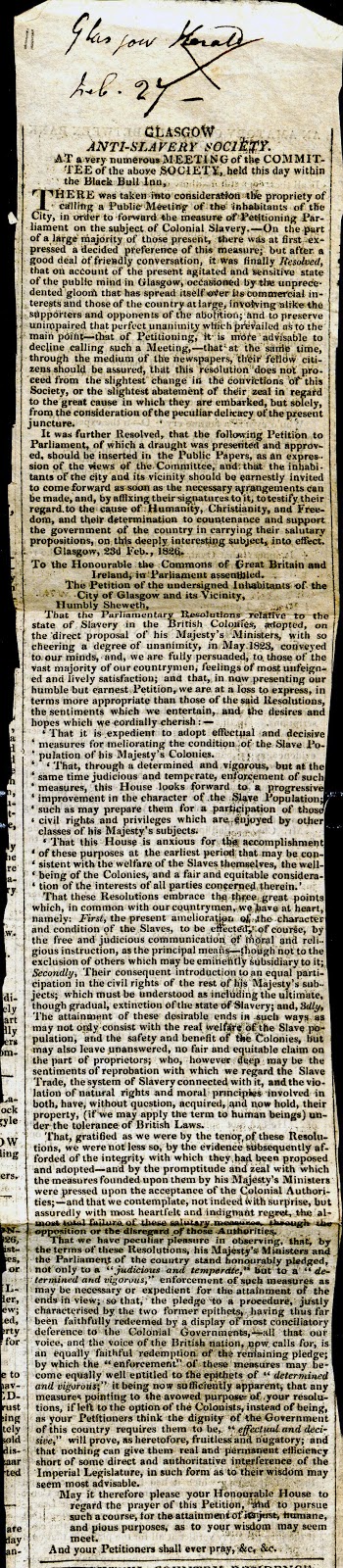

Newspaper reports, such as the one below from the Glasgow Herald of 27 February 1826, provided further publicity.

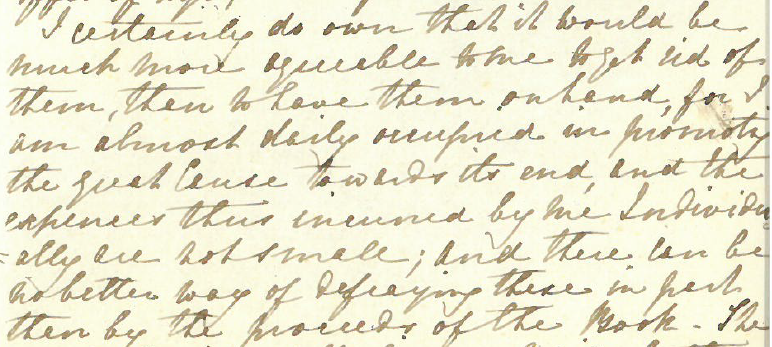

And sales from Clarkson’s books could raise money along with awareness: in a 10 February 1813 letter to John Wadkin, Clarkson discusses his Memoirs of the Life of William Penn (the founder of Pennsylvania), sets of which Wadkin is endeavouring to sell.

I certainly do own that it would be much more agreeable to me to get rid of them, than to have them on hand, for I am almost daily occupied in promoting the great Cause towards its end, and the expenses thus incurred by me Individually are not small; and there can be no better way of defraying these in part than by the proceeds of the Book.

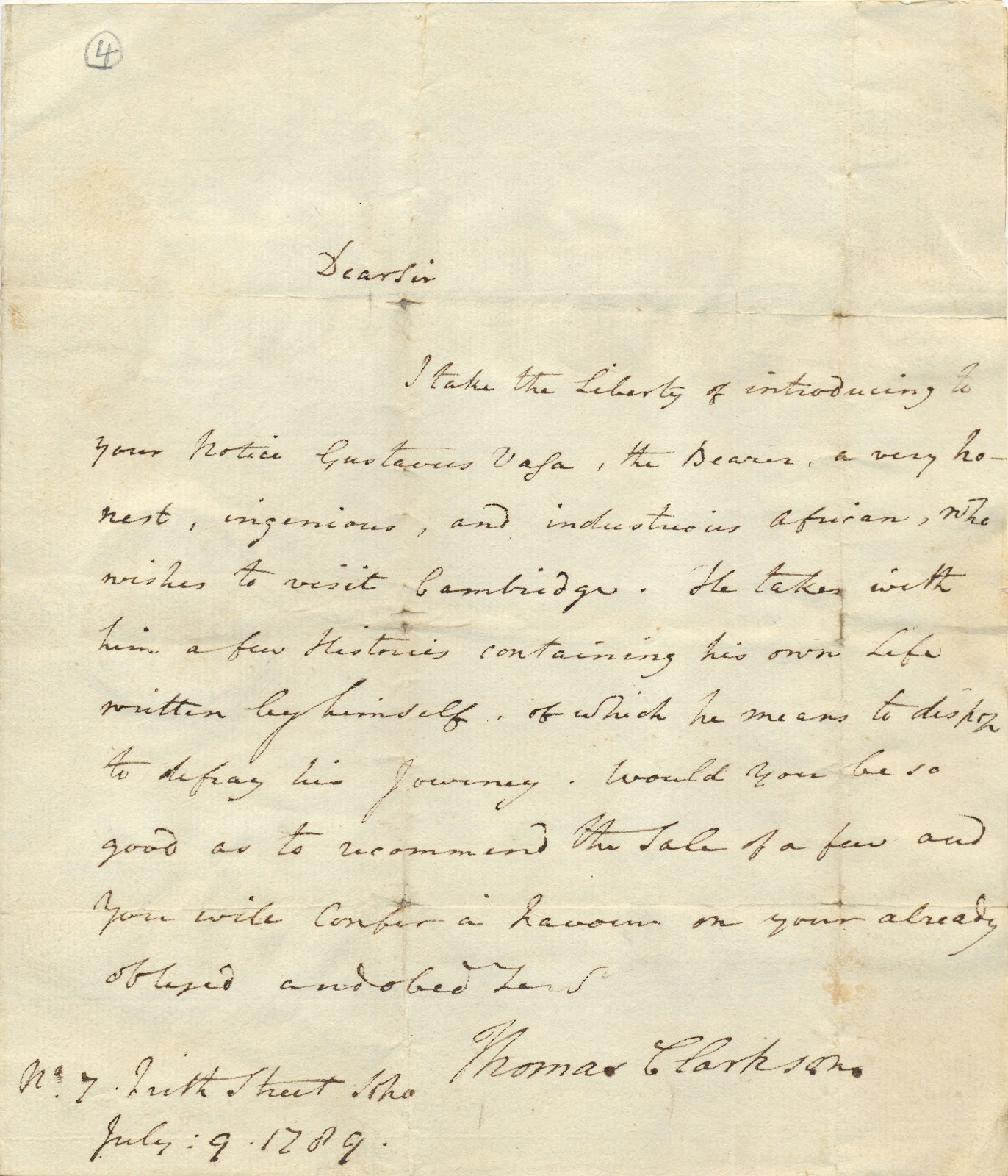

Of course, Clarkson was far from the only campaigner to fund himself, in part, through writing. In the below letter of 9 July 1789, Clarkson writes to the Reverend Dr Jones of Trinity College, Cambridge, to bring to his notice Gustavus Vasa, ‘a very honest, ingenious, and industrious African, who wishes to visit Cambridge.’

‘Gustavus Vasa’ was a name adopted by Olaudah Equiano, originally from the Kingdom of Benin (in modern Nigeria), who was enslaved as a child but purchased his freedom in 1766, in his early twenties. He became part of the British abolitionist movement, and a member of a London-based Black campaigning group, the Sons of Africa. At the time of Clarkson’s letter, Equiano/Vasa had just published an autobiography, copies of which ‘he means to dispose [of], to defray his journey’; Clarkson asks if Jones will ‘recommend the Sale of a few’.

Could Clarkson also mount an economic argument against the slave trade? In An Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade, he argues that there are desirable woods, dyes, foodstuffs, medicines and other products that could usefully be bought from African countries, and that the focus on slavery is a hindrance to a more constructive economic relationship.

This account [...] will give the reader an additional proof of the riches to be found in the African soil. He will see the great advantages, which would result from a trade in these alone. But he will never be able to estimate the loss which we sustain by the trade in slaves, which hinders the country from being farther explored, and those inexhaustible treasures from coming forth, which are now buried and concealed.

One might take issue with the broad conception of a multifaceted continent as ‘the country’, and with the dangerous hyperbole of ‘inexhaustible’. But Clarkson was addressing an audience that required convincing, and detailed arguments must sometimes be sold through broad gestures.

Clarkson supported his case not only with the idea of these products, but with the products themselves. Since 1870, the collection at Wisbech & Fenland Museum has included Clarkson’s campaign chest, which is currently the subject of research connected to the Articles for Change project.

The chest contains African produce – whose unknown points of origin are being investigated through close analysis – alongside instruments of restraint. Starting with textiles such as those pictured below, Clarkson collected items from the ports of London, Bristol and Liverpool, and was given others by the Swedish naturalist and abolitionist Dr Anders Sparrman.

A seed tray, gesturing at the range of the continent’s agriculture, was also included. Sugar production in Jamaica was, as the letters from William Perrin’s plantations show, a sensitive process, the quality (and therefore the price) of the sugar largely dependent upon an ideal pattern, rarely realised, of rainy and dry seasons. Importers in Great Britain might have been drawn to the possibility of a greater diversity of products, cheaper to ship because closer to home.

The textiles from the campaign chest helped to recruit Wilberforce to the cause; and the chest was part of the evidence seen by the 1788 Privy Council inquiry into the trade. Items from it were also shown to Emperor Alexander I of Russia, when Clarkson met him in Paris on 23 September 1815.

In the above print by Charles Turner, from a portrait by Alfred Edward Chalon, Clarkson is seen alongside the chest, with busts of Wilberforce and fellow abolitionist Granville Sharp also in view.

It must be recognised that a more diverse trading relationship is not necessarily a less exploitative one. There is no reason to believe that Clarkson himself was, uncharacteristically, being cynical when he suggested this different sort of dynamic between the British Empire and Africa: he was not implying that the latter’s function was to fill the pockets of the former, and indeed was making an argument for the intelligence and sophistication of Africa’s people. But others might have placed a cynical interpretation upon his arguments, if possessed of a worldview in which ‘civilised’ people can bring their version of civilisation to other cultures, with profit as the goal.

Civilisation and savagery

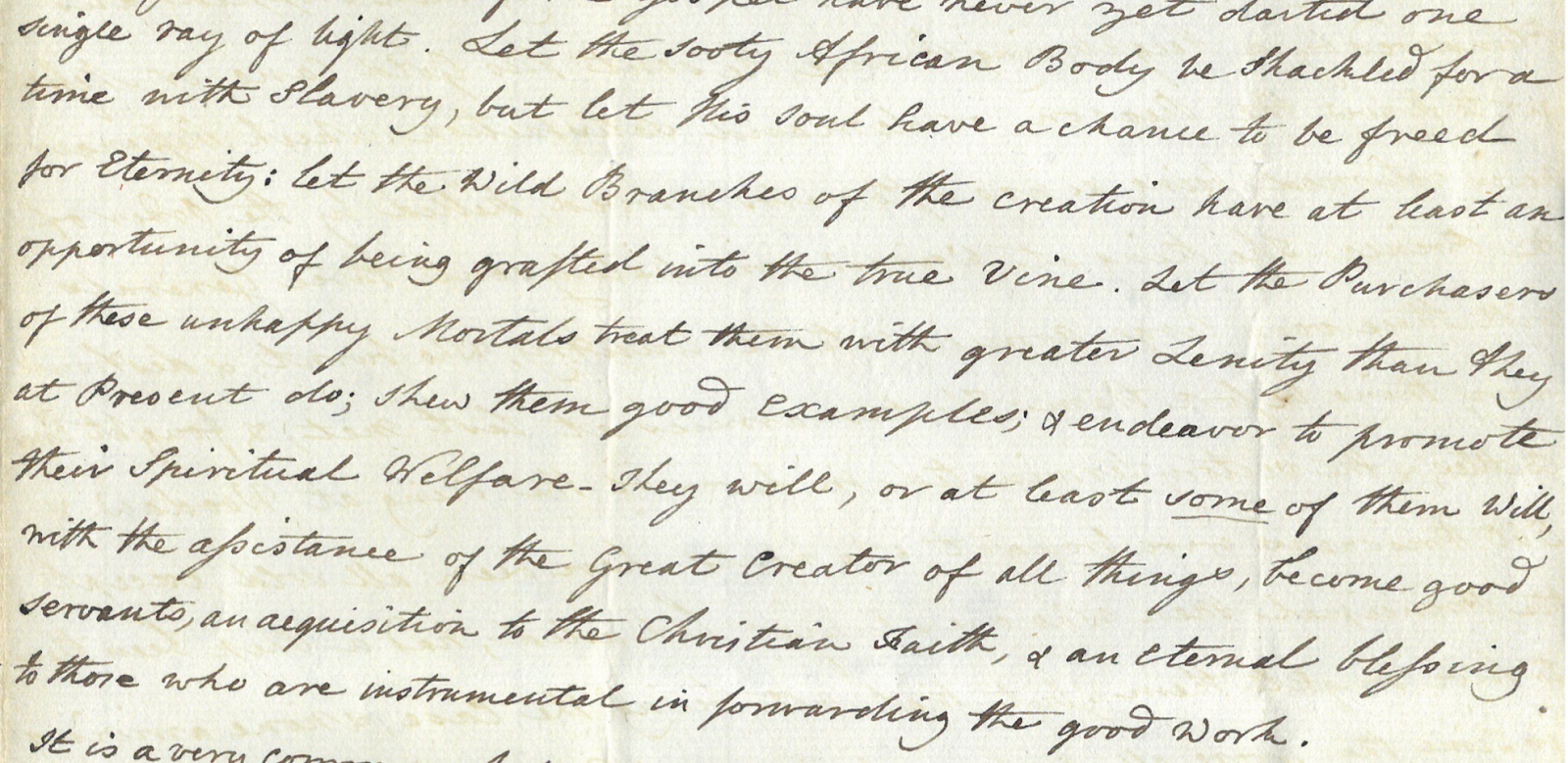

The arguments in defence of the slave trade did not always manifest as economic ones, even if money likely lay at the root. One letter of around 1800, included in the Perrin correspondence, is addressed ‘To the Printer’ and thus evidently intended for publication. Written by one ‘Africanus’ – emphatically not the Black abolitionist Ignatius Sancho, who used that pen name but died in 1780 – the letter argues the moral case in favour of the trade. The suggestion is that Africans will benefit from being removed from their native cultures and introduced to Christianity.

Let the sooty African Body be shackled for a time with Slavery, but let his soul have a chance to be freed for Eternity: let the Wild Branches of the creation have at least an opportunity of being grafted into the true Vine. Let the Purchaser of these unhappy Mortals treat them with greater Lenity than they at Present do; shew them good examples; & endeavor to promote their Spiritual Welfare. They will, or at least some of them will, with the assistance of the Great Creator of all things, become good servants, an acquisition to the Christian Faith, & an eternal blessing to those who are instrumental in forwarding the good work.

The thrust of the argument is that those sold into slavery had been captured and enslaved already: life was already hard and unhappy for them. And if slavery is a person’s lot, is it not better that they be enslaved to white Christians?

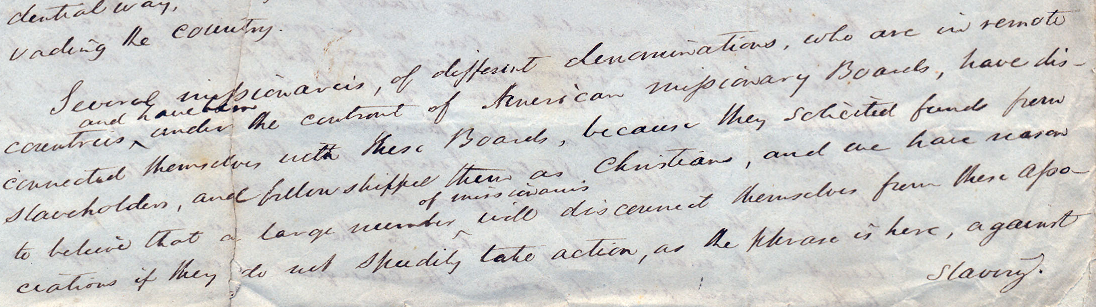

Of course, many abolitionists were people of faith, and not all Christians took the position of this ‘Africanus’. In a letter to Clarkson of 29 February 1844, Lewis Tappan writes the following from New York.

Several missionaries, of different denominations, who are in remote countries and have been under the control of American missionary Boards, have disconnected themselves with these Boards, because they solicited funds from slaveholders, and fellowshipped them as Christians, and we have reason to believe that a large number of missionaries will disconnect themselves from these associations if they do not speedily take action, as the phrase is here, against slavery.

Some found slavery compatible with their faith, and others did not. There seems to have been a struggle between personal and collective conscience, between individual morality and a structurally embedded interest in maintaining current systems.

A belief in the status quo could be impressed upon people at a young age. The History of Tommy, the Little Black Boy is a children’s chapbook dating, like Africanus’s letter, from around 1800. It concerns Tommy, a slave on a plantation, being taught to read. The narrative praises him for his hard work and obedience, and somewhat implausibly concludes with him being crowned king of ‘the Indians’, who are so impressed by him that they purchase his freedom: ‘Thus Tommy (though a black), by minding his book, and doing as he was bid, from being the son of a slave, is now become a king.’ The more sober reality was that reading was a specialist skill much like, say, carpentry, and a slave with such skills could be sold for higher prices.

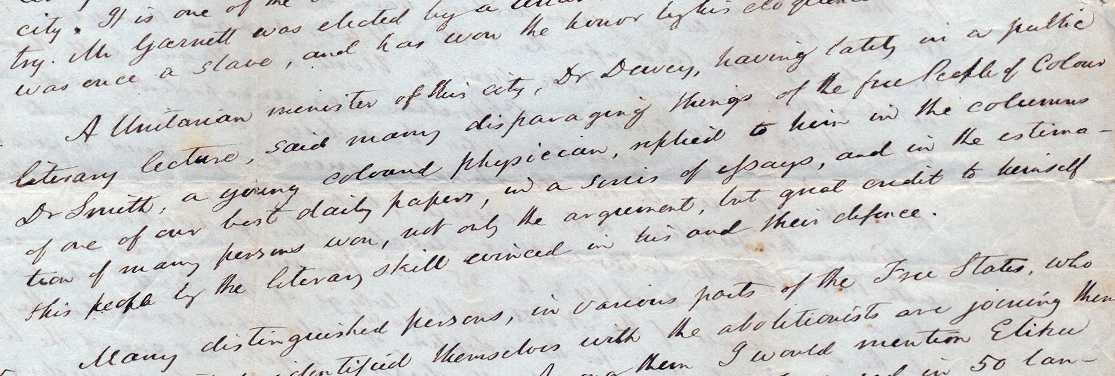

Tappan mentions literacy, indeed literariness, in a different context.

A Unitarian minister of this city [New York], Dr Davey, having lately in a public literary lecture, said many disparaging things of the free People of Colour[,] Dr Smith, a young coloured physician, replied to him in the columns of one of our best daily papers, in a series of essays, and in the estimation of many persons won, not only the argument, but great credit to himself & his people by the literary skill evinced in his and their defence.

A reevaluation of persecution should not require such a demonstration by the persecuted. But there is still something to be said for the disabling of prejudice. Tappan also mentions the election of a former slave, Henry H. Garnett, to a literary society, and nods to two fledgling newspapers (the Philadelphia Elevator and the Hartford Clarksonian) founded and edited by people of colour.

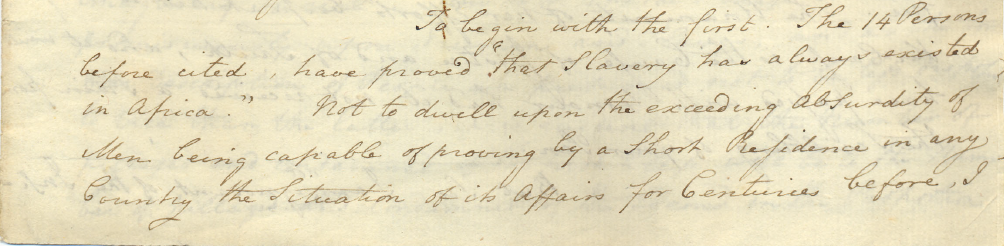

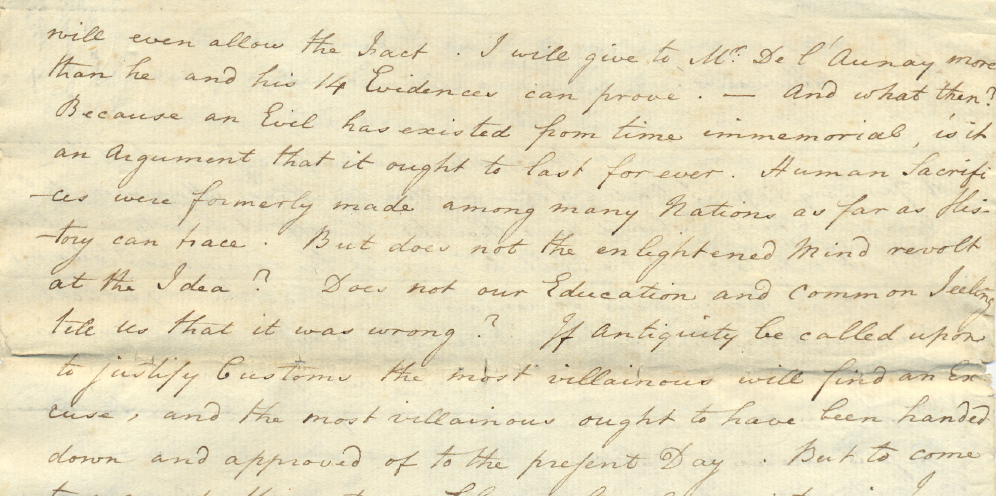

These are indications of changing values. In a draft essay of around 1790, Thomas Clarkson attacks the assertion, by those advocates of slavery who claim to understand African history, that the slave trade can be justified by precedent.

Not to dwell upon the exceeding absurdity of Men being capable of proving by a Short Residence in any Country the Situation of its Affairs for Centuries before, I will even allow the Fact. [...] And what then? Because an Evil has existed from time immemorial, is it an Argument that it ought to last for ever? Human Sacrifices were formerly made among many Nations as far as History can trace. But does not the enlightened Mind revolt at the Idea? Does not our Education and common feeling tell us that it was wrong? If Antiquity be called upon to justify Customs the most villainous will find an excuse, and the most villainous ought to have been handed down and approved of to the present Day.

On 2 March 1844, Joseph Soul wrote to Clarkson with regard to the case of a man in the United States given a death sentence for aiding an escaped slave. ‘It is a most melancholy affair’, Soul observes, ‘and one would suppose only likely to be perpetrated by a nation of Savages.’ People might condemn alleged savagery elsewhere, but, Soul implies, are unlikely to recognise it in themselves.

Cognitive dissonance

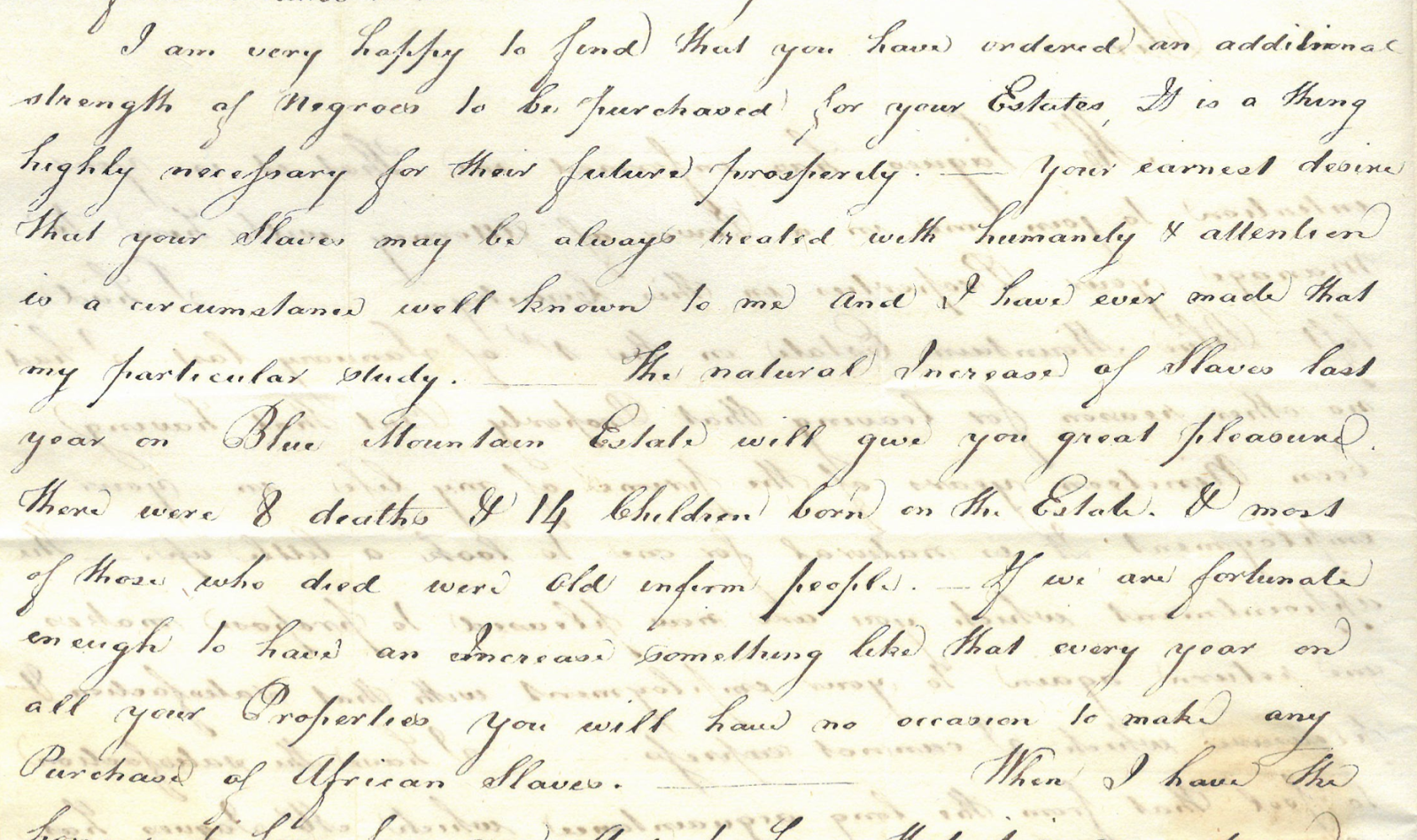

William Perrin seemingly believed, or wished to be assured, that he was not a cruel man. Referring to a recent purchase of slaves, William Sutherland mentions, in a letter written on 23 February 1794, Perrin’s ‘earnest desire that [his] Slaves may be always treated with humanity & attention’. Yet in the same paragraph he writes about death and birth rates on the estates: ‘If we are fortunate enough to have an Increase something like that every year on all your Properties you will have no occasion to make any Purchase of African Slaves.’

Did Sutherland truly believe there was ‘humanity’ in discussing the economic benefits of birth rates among enslaved people; was he strictly compartmentalising his thoughts; or was he simply writing what his employer wanted to read?

Jaques & Fisher claim, in a letter of 23 June 1791, that ‘[n]o people can be treated with greater tenderness’ than are the slaves on the Perrin estates; referring on 13 July 1796 to another purchase of slaves from one Dr Affleck, Sutherland tells Perrin that ‘all the Negroes were highly pleased & well satisfied at having been purchased for you’. It is fair to assume that this is not the full story, although it is conceivable that an estate whose owner was allegedly interested in ‘humanity’ was slightly preferable to an estate run on no such principle. One might at least expect consequences for those inclined to abuse their position: writing on 26 July 1800, Jaques, Laing & Ewing report the firing of the overseer of Perrin’s Blue Mountain estate, ‘not on account of any defect as a planter but for the harsh & we may say bordering on cruel Treatment of the Negroes particularly of the pregnant Women’.

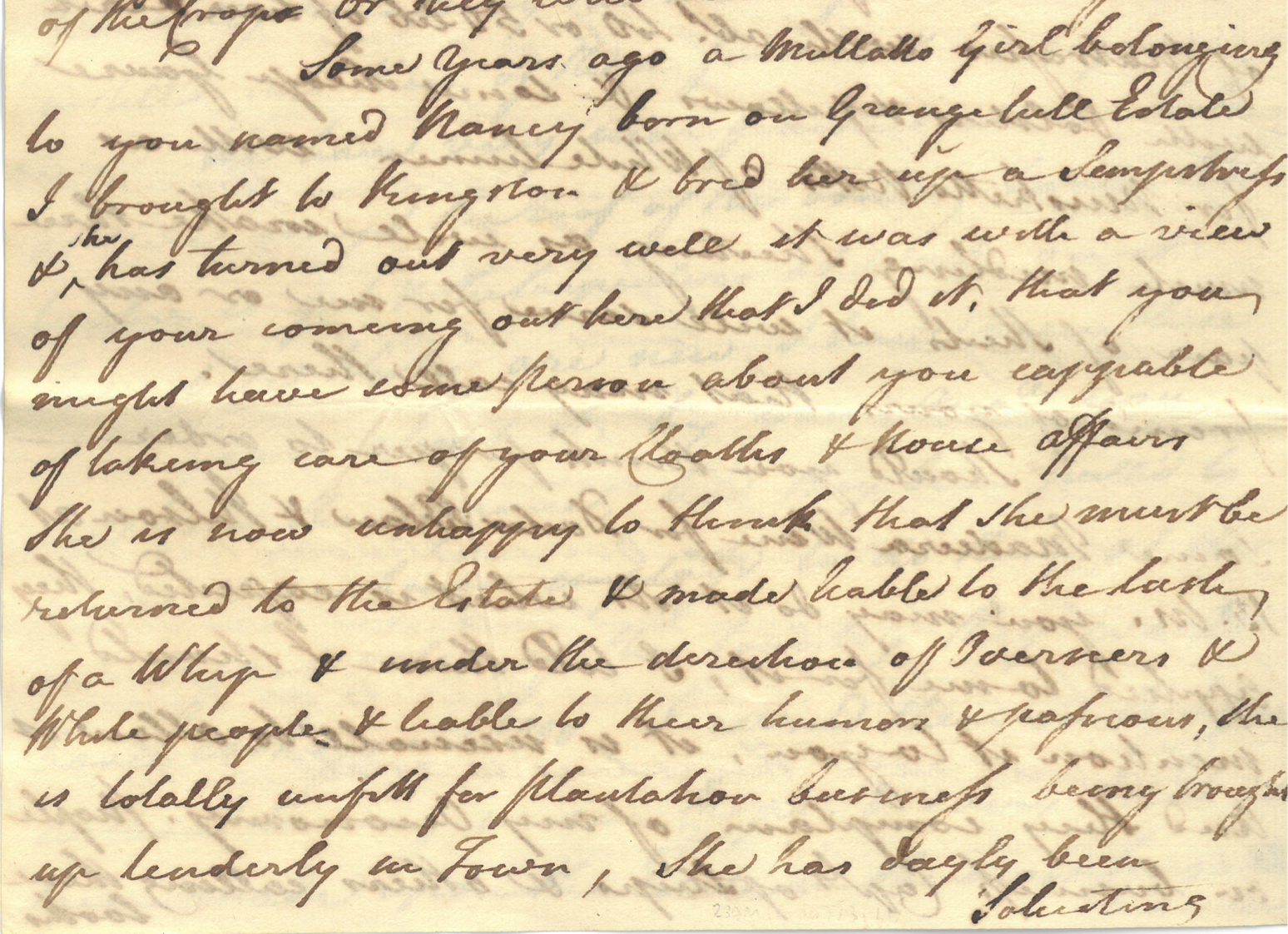

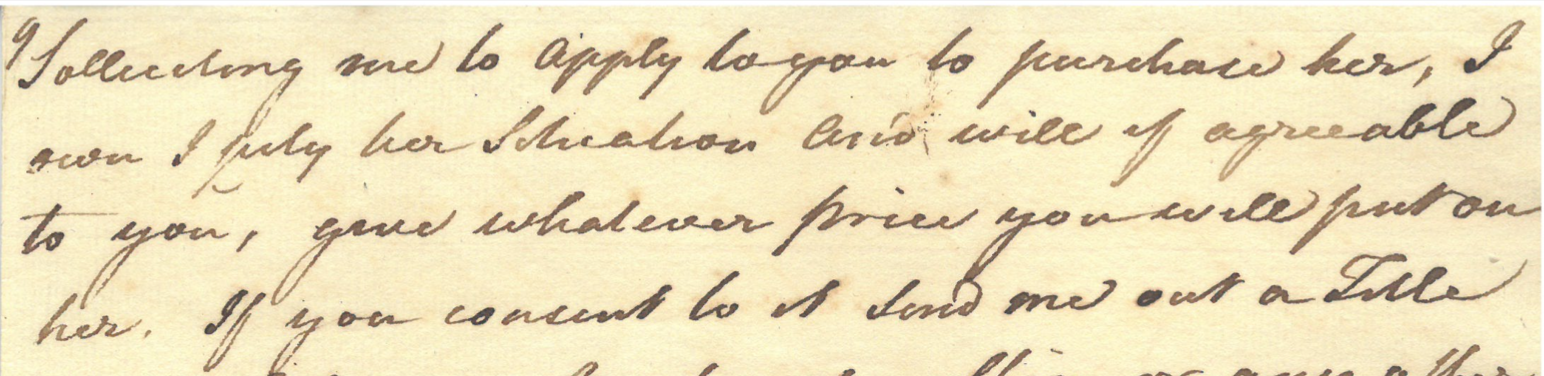

Sometimes this supposed 'tenderness', albeit directed towards people considered property, takes a more personal form. Malcolm Laing writes the following in a letter to Perrin of 25 January 1774.

Some years ago a Mullatto Girl belonging to you named Nancy born on Grange Hill Estate I brought to Kingston & bred her up a Sempstress & she has turned out very well it was with a view of your coming out here that I did it, that you might have some person about you cappable of taking care of your Cloaths & House affairs. She is now unhappy to think that she must be returned to the Estate & made liable to the lash of a Whip & under the derection of Overseers & White people & liable to their humors & passions, she is totally unfitt for Plantation business being brought up tenderly in Town. She has dayly been Solliciting me to apply to you to purchase her, I own I pity her Situation and will if agreeable to you, give whatever price you will put on her.

Laing’s criteria against Nancy being sent to a plantation are striking: violent treatment, and lack of capacity for hard physical labour. One might ask why these are objectionable prospects for Nancy but not for other enslaved people, and wonder if Laing's sympathies stem from Nancy's being of mixed ethnicity or from other factors.

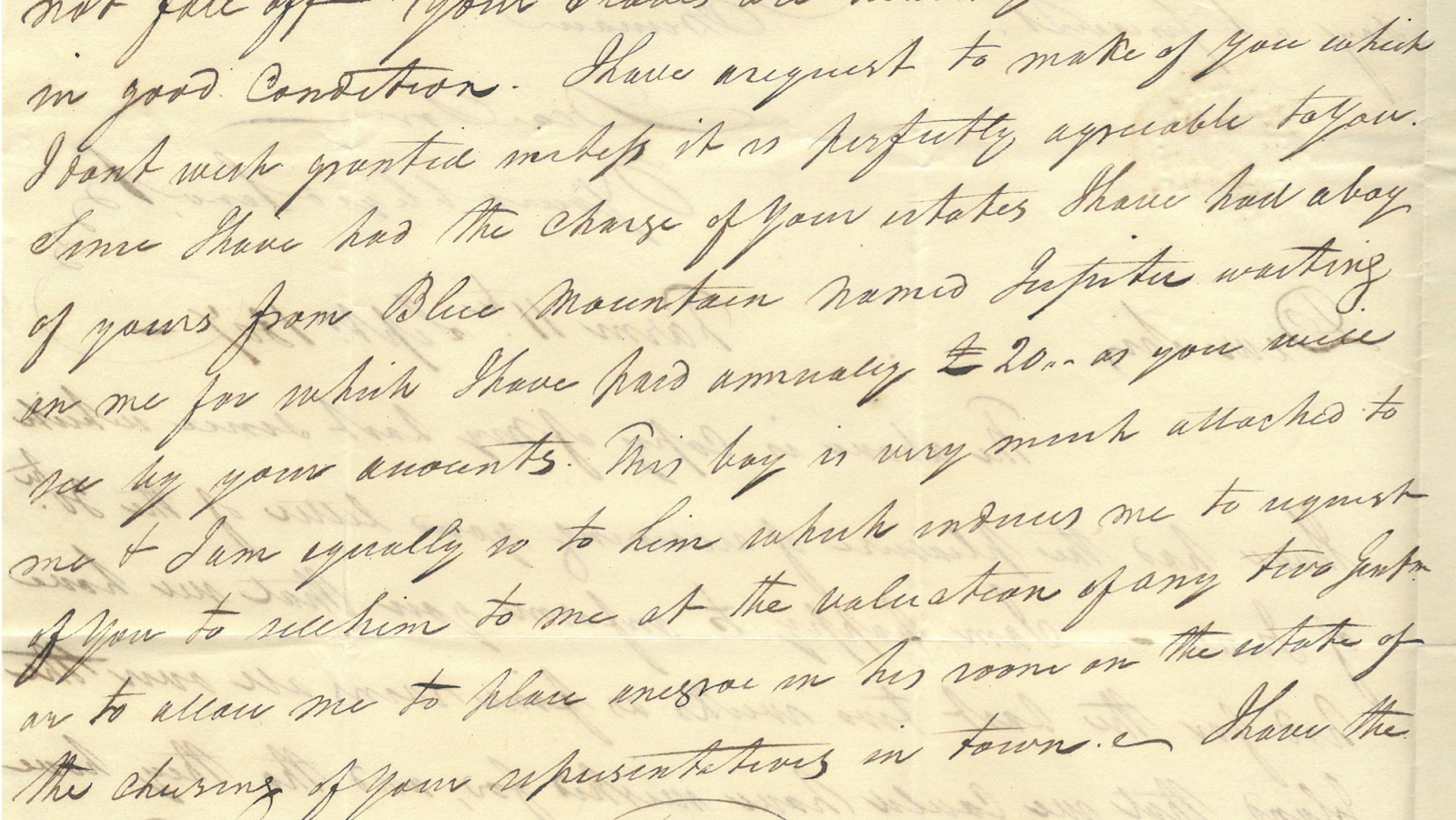

Writing to Perrin on 15 August 1807, Francis Graham offers a similar expression of fondness towards an enslaved person.

I have a request to make of you which I dont wish granted unless it is perfectly agreeable to you. Since I have had the charge of your estates I have had a boy of yours from Blue Mountain named Jupiter waiting on me for which I have paid annually £20 as you will see by your accounts. This boy is very much attached to me & I am equally so to him which induces me to request of you to sell him to me at the valuation of any two Gentlemen or to allow me to place a negroe in his room on the estate of the chusing of your representatives in town.

One can only guess at whether Graham believed he was buying a slave for himself or buying Jupiter’s freedom, and at the extent to which Jupiter did indeed reciprocate the feelings of attachment. Another letter in the collection confirms that the sale was approved.

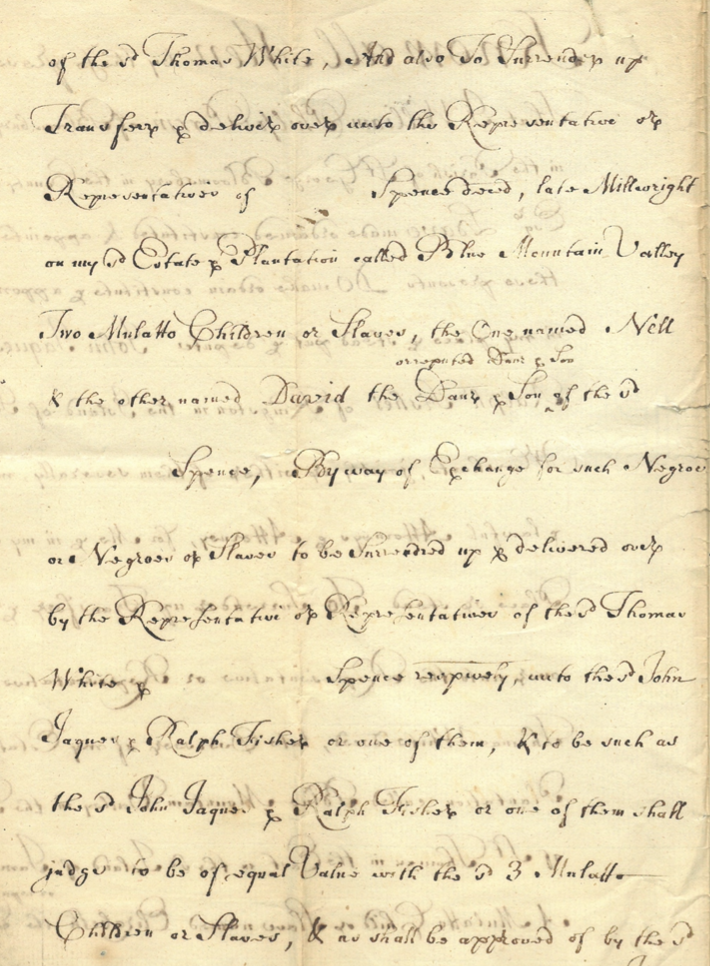

Nancy and Jupiter are rarities in the Perrin papers, being mentioned by name in a context other than detached monetary valuation. Also present is documentation (28 November 1783) relating to the sale of three children fathered on enslaved women by two of Perrin’s former employees: Elizabeth is being sold to her father, Thomas White, while a man named Spencer is the father of Nell and David. Perrin agrees in the power-of-attorney document that the children can become their fathers’ property ‘By way of Exchange for such a Negroe or Negroes or Slaves […] to be such as the said John Jaques & Ralph Fisher or one of them shall judge to be of equal Value with the said 3 Mulatto Children or Slaves’.

Any suggestion of familial warmth is underpinned by economics: love and compassion (if those are even at work here) are acceptable as long as the slaveowner is not making a loss. It might be mentioned, for context, that there is a series of letters to Perrin in which concern is expressed over the mental state, ill health and eventual death of a bull: as slaves and livestock were often thought of in similar terms, one cannot assume that, when a correspondent expresses sympathy towards an enslaved person, they are necessarily giving full recognition to that person's humanity.

Outrages upon human nature

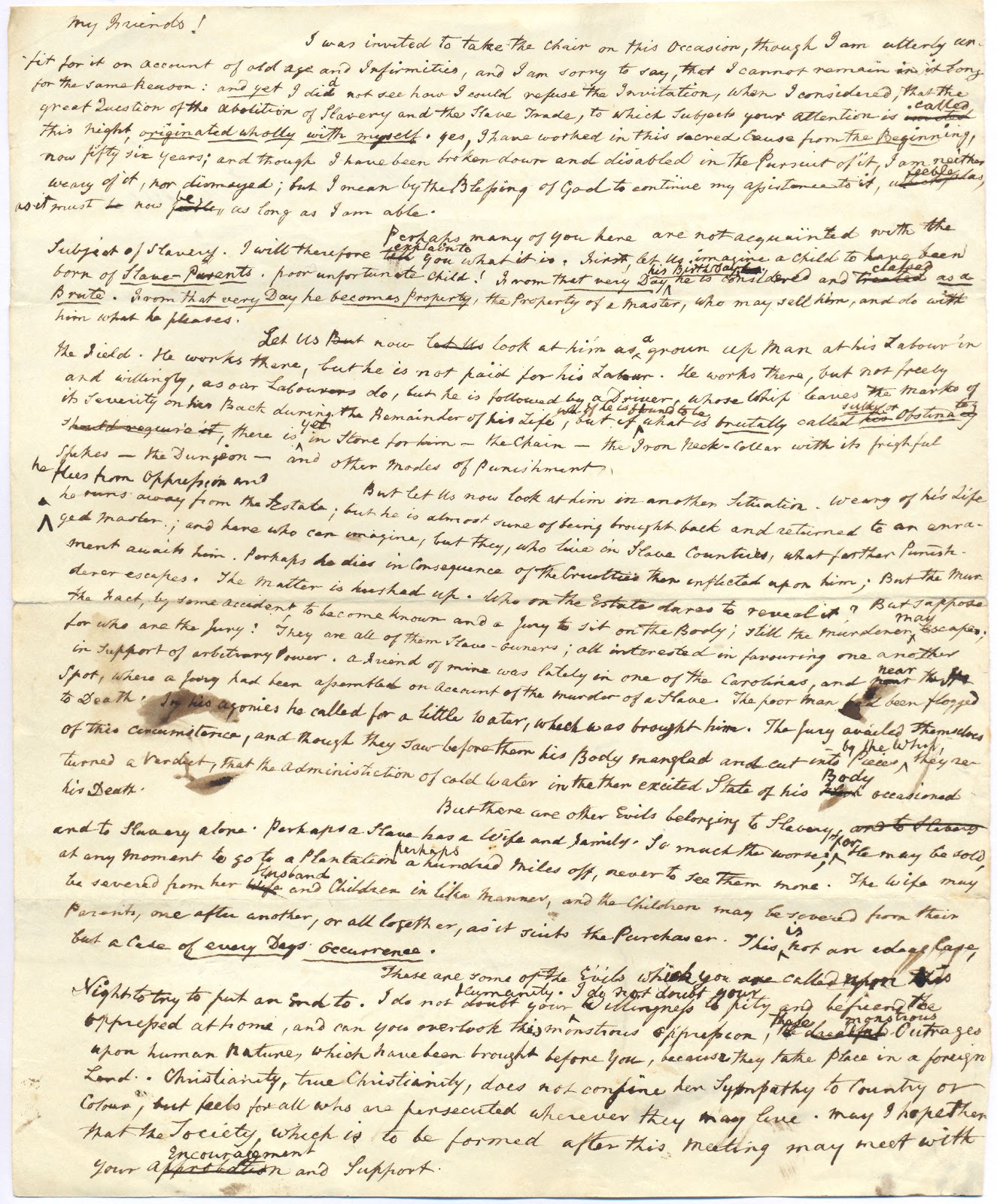

In September 1840, Clarkson, eighty years old, gave a speech in Ipswich in which he summarised his life of campaigning. The Library’s collections include a draft of the speech.

Clarkson asks his audience to consider the life of a slave as the life of a human being, and to respond as they would to any other human life in a state of misery. As can be seen in the draft, and in the transcript below, Clarkson’s argument is that persecution cannot be considered selectively: people have a responsibility to oppose injustice globally, not only where it immediately affects them.

My Friends!

I was invited to take the Chair on this occasion, though I am utterly unfit for it on account of old age and infirmities, and I am sorry to say, that I cannot remain in it long for the same reason: and yet I did not see how I could refuse the invitation, when I considered, that the great question of the abolition of slavery and the slave trade, to which subjects your attention is called this night, originated wholly with myself. Yes, I have worked in this sacred cause from the beginning, now fifty six years; and though I have been broken down and disabled in the pursuit of it, I am neither weary of it nor dismayed; but I mean by the blessing of God to continue my assistance to it, feeble as it must now be, as long as I am able.

Perhaps many of you here are not acquainted with the subject of slavery. I will therefore explain to you what it is. First let us imagine a child to have been born of slave parents. poor unfortunate child! From that very day, his birthday, he is considered and classed as a brute. From that very day he becomes property, the property of a master, who may sell him, and do with him what he pleases.

Let us now look at him as a grown up man at his labour in the field. He works there, but he is not paid for his labour. He works there, but not freely and willingly, as our labourers do, but he is followed by a driver, whose whip leaves the marks of its severity on his back during the remainder of his life, but if he is found to be what is brutally called sulky or obstinate there is yet in store for him – the chain – the iron neck-collar with its frightful spikes – the dungeon – and other modes of punishment.

But let us now look at him in another situation. Weary of his life he flees from oppression and he runs away from the estate; but he is almost sure of being brought back and returned to an enraged master; and here who can imagine, but they, who live in slave countries, what further punishment awaits him. Perhaps he dies in consequence of the cruelties then inflicted upon him; but the murderer escapes. The matter is hushed up. Who on the estate dares to reveal it? But suppose the fact, by some accident, to become known and a jury to sit on the body; still the murderer may escape for who are the jury? They are all of them slave-owners; all interested in favouring one another in support of arbitrary power. A friend of mine was lately in one of the Carolines, and near the spot, where a jury had been appointed on account of the murder of a slave. The poor man had been flogged to death. In his agonies he called for a little water, which was brought him. The jury availed themselves of this circumstance, and though they saw before them his body mangled and cut into pieces by the whip, they returned a verdict, that the administration of cold water in the then excited state of his body occasioned his death.

But there are other evils belonging to slavery, and to slavery alone. Perhaps a slave has a wife and family. So much the worse for he may be sold at any moment to go to a plantation perhaps a hundred miles off, never to see them more. The wife may be severed from her husband and children in like manner, and the children may be severed from their parents, one after another, or all together, as it suits the purchaser. This is not an ideal case, but a case of every days occurrence.

These are some of the evils which you are called upon this night to try to put an end to. I do not doubt your humanity. I do not doubt your willingness to pity and befriend the oppressed at home, and can you overlook this monstrous oppression, these monstrous outrages upon human nature which have been brought before you, because they take place in a foreign land. Christianity, true Christianity, does not confine her sympathy to country or colour, but feels for all who are persecuted wherever they may live. May I hope then that the Society which is to be formed after this meeting may meet with your encouragement and support.’

The better part of two centuries later, the observation that people's sympathies are sometimes thus ‘confine[d]’ might still ring true.

A discussion

As the pandemic made it impossible to hold the usual sort of exhibition, in which visitors can mingle around display cases and discuss the items with one another and with Library and Museum staff, we decided to arrange a panel discussion in which contributors could respond to the material and the issues raised. The video can be viewed on the St John's College YouTube channel, or below.

Hosted by Adam Crothers (Special Collections Assistant at St John's), the panel includes:

Carol Brown-Leonardi (Open University)

Sabine Cadeau (University of Cambridge)

Maaha Elahi (St John's College, Cambridge)

Rebecca Nelson (University of Hull)

Opinions are the speakers' own and do not necessarily reflect those of their institutions. The conversation was recorded over Zoom on Monday 15 March 2021, and has been edited for length and clarity. References to racial injustice, past and present, occur throughout.