From Pulp to Fictions: Fellow’s new book uncovers England’s cultural history of paper

"The moment Medieval people found ways of making paper, they found new ways of using it"

A St John’s academic is rewriting the story of how paper transformed Medieval England.

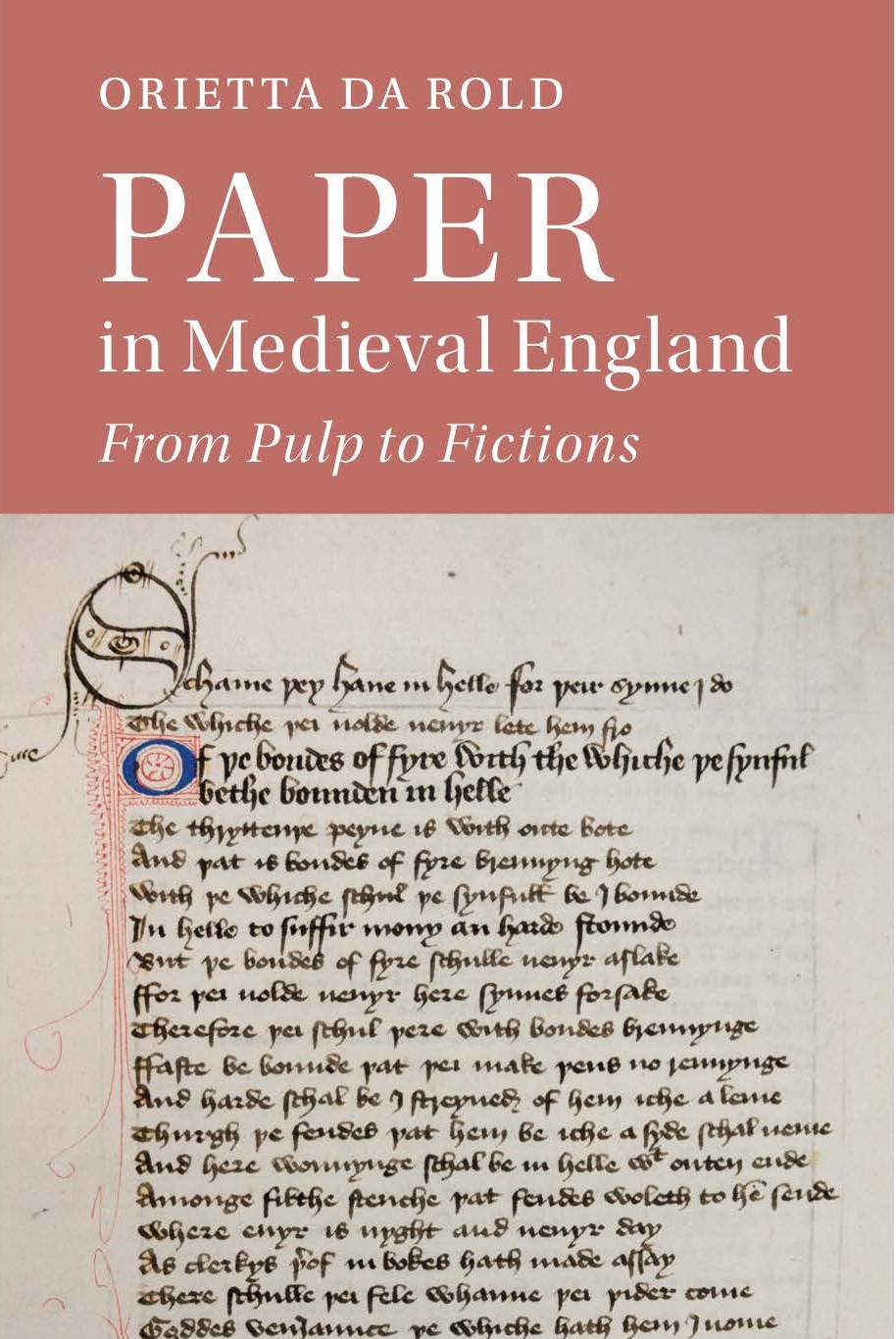

Dr Orietta Da Rold, an expert in Medieval literature and manuscripts, has examined the coming of paper to England during the Middle Ages, and its influence on the culture and society of the period, in her new book, Paper in Medieval England: From Pulp to Fictions.

In the book, she explores the early uses of paper and its success as a technology. Dr Da Rold, College Lecturer in English, University Lecturer in Medieval Literature and the Material Text, 1100-1500, and a Fellow of St John’s, said her findings call into question perceived knowledge about Medieval paper and shed light on the pre-modern, pre-printing period, revealing a multi-layered cultural history.

Before the arrival of paper in England, most writing was on parchment, made from animal skin. Paper is often seen as a revolutionary technology but, although it was quickly adopted by the English, its domination took time, according to Dr Da Rold. She said: “When people talk about the invention of paper, they talk about revolution. In reality, it wasn’t so much a revolution as an evolution, although even that isn’t the right term. Something new was invented and slowly it began to be used in all sorts of environments, because people started trying it out, then improving it and adapting it for their own needs.”

Paper made from pulped rags originated in China and was introduced to the West from the Arab world in the 11th century, before being brought to England via mainland Europe towards the 13th century. By the end of the 14th century, this new material was being used in a large variety of ways, for writing letters and producing books, to dressing wounds. In her research, Dr Da Rold noted that different qualities of paper were produced – the top quality being ‘royal’ paper made and imported in smaller quantities. Larger quantities of small format paper were imported for writing and keeping accounts, but paper was also sought out for wrapping goods, such as foodstuffs and even gifts.

“The main paper really circulating in England during this period was lesser quality paper that could be used for wrapping goods, or for shredding or storing things,” explained Dr Da Rold. “We know that in the later centuries this is the case, but it just didn’t click with me before that this was happening much earlier.

“As book historians we always look at paper for writing, so it was a surprise to find out there were all these other types of paper used for different purposes, just as we use it today: from paper for printing and beautiful handmade paper, to toilet paper. This is one of the arguments in my book, that when we talk about paper in the Medieval period, we need to talk about the immense varieties of paper, different sizes and colours, and purposes. All these variations actually started with the production of this technology and people chose what was best for their needs; it is the affordances of this technology that is so surprising rather than the affordability.”

The availability of paper created all sorts of possibilities, especially at retail level. “We have accounts of a butcher using paper to wrap salami, and of people buying clean white paper to wrap sweets made with roses, and even to whiten their teeth. It was extremely versatile. The moment Medieval people found ways of making paper, they found new ways of using it,” said Dr Da Rold.

"It is just human to keep on improving things, it’s in our DNA"

Paper was adopted very quickly in everyday life in England and, for a long time, parchment continued to be used alongside it. Sometimes the two materials were combined and together they contributed to the increase in demand in writing materials, and the subsequent explosion in the sharing of ideas, knowledge, and literature. Paper was a concept as well as a tool. “If you think about the mobile phones of the Eighties and Nineties, they were like a brick compared to the smartphones we have now. It is just human to keep on improving things, it’s in our DNA. At any moment in time invention can be seen as a revolution. But the term ‘revolution’ is difficult because it implies belligerence, two technologies fighting each other, and I don’t see evidence of that,” said Dr Da Rold.

“Effectively the main scholarly discourse on the reason why Medieval people chose paper over anything else is because it was cheap and it was of lower status – that’s the starting point of any academic book. I just thought that it didn’t make any sense, we don’t use an iPhone because it’s cheap. What I really wanted to demonstrate in my book is that the choice of material and written technology was down to social preferences, it’s not so much about status and cost, it’s about culture.”

In 2014 Dr Da Rold led a project called Mapping Paper in Medieval England, and in 2015 she and her team trawled archives across the country in search of manuscripts in a bid to establish how paper use spread across England between 1300 and 1475, when William Caxton set up the first printing press. A British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship enabled Dr Da Rold to write her new book and she is now working on a follow-up, Paper in Time and Space.

- Paper in Medieval England: From Pulp to Fictions is published in hardback and as an eBook by Cambridge University Press. In addition, The Cambridge Companion to Medieval British Manuscripts edited by Dr Da Rold and Professor Elaine Treharne (Stanford University) is due out this month in paperback.

Published: 14/12/20