When solemn dictates fail

There is nothing, in reality, where people are so very wrong as in the education of children, though there is nothing in which they ought to be more absolutely certain of being right: If we seriously reflect upon the customary method in which children are brought up, we must almost imagine, that the generality of parents inculcate principles of religion into their offspring, for the mere satisfaction of bringing both religion and virtue into contempt; and paint the precepts of morality in the most engaging colours, to show, by their practice, how much these precepts are to be despised.

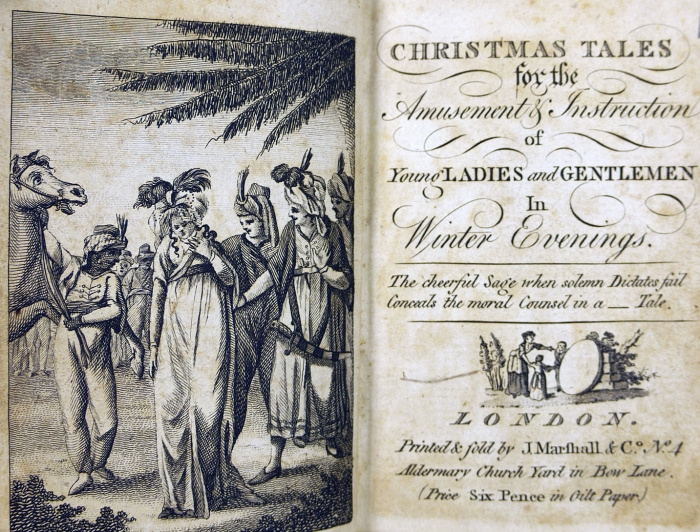

Thus begins Christmas Tales for the Amusement & Instruction of Young Ladies and Gentlemen in Winter Evenings (circa 1785) by Solomon Sobersides, the first item in a multi-text volume once owned by John Couch Adams.

The book contains thirteen tales, and begins with one concerning a man who, having been corrupted into ingratitude by money, is sufficiently chastised by his young son, 'little Tommy', to change his ways; in the second, a man who barely talks reveals, when being exhorted to speak ill of people, that his policy is one of only speaking when he has something positive to say. So far, so vaguely Dickensian; but this book is pre-Dickens, pre-Victorian, and therefore pre-Christmas as many in the West now know it. The stories’ shift towards themes of mystical goings-on in the Middle East might feel distinctly unseasonal, then, at least until one recalls that the Christmas story that gave the season its name is concerned with precisely that sort of activity. Festive traditions pertaining to snow, ghosts and not hacking one’s thieving servant into pieces in order to make a point are relatively recent inventions.

The longer tales give the impression of having been made up in the telling, and in a confused rather than an inspired fashion that leaves one wanting instruction and indeed amusement: witness that of the boy who steals in various ways from a dervish, only to be beaten up by ghosts that emerge from an enchanted candlestick, when all he wanted was for them to turn into diamonds. In comparison to the pithier fables against ingratitude and impatience, the convolution of this particular narrative is such that its moral lesson can only be taken as: don’t in the first place steal from a dervish, and if you do insist upon trying to exploit his enchanted candlestick for financial gain, make sure you hold your staff in the correct hand when you hit the ghosts. Which is not of zero real-world application, but the situation comes up only rarely. On the other hand, there is interest to be found in the extent to which the 'principles of religion' do not always take Christianity as their foundation: most strikingly, one story features a Muslim man whose faith compels him to shelter, and provide safe passage to, the Christian who has murdered his son.

Yet the tidier moral teachings can comes across as variously misjudged and lacking in nuance. Another story is set in Lapland, and follows King Hacho, who, after consuming wild honey out of necessity, becomes accustomed to delicacies and comfort rather than to war. This initially seems rather more in keeping with the peaceful and merry-making aspects of post-A Christmas Carol Christmas. But then Hacho is killed by the King of Norway and wishes as he dies that he had remained bellicose, and blames the temptations of honey for his downfall: if the reader learns a lesson about responsibilities and resolve, it is not a heartwarming one. Still, while the moral of the final story, set in China – that it is better to show kindness to one person than to have thousands of people subjected to your will – might seem comically broad and obvious, 2017 has not been a year in which humankind demonstrated its commitment to that ideal. So the book might still be worth a read.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 1 December 2017 by Adam Crothers, Special Collections Assistant.