Visions of the End:

Selected Apocalypses from the Library

Introduction

This exhibition, curated in May 2021, comes after more than a year of the coronavirus pandemic, during which Special Collections staff have been working primarily from home. Our exhibitions have taken place online, and we have carried out work for enquirers remotely; readers have not used the Rare Books Reading Room, and the Upper Library has been populated by excess chairs removed, for reasons of social distancing, from the Working Library. We’ve been luckier than many, and the world has not ended; but now some cautious optimism begins to seem justified, at least locally, and the Special Collections Assistant, Adam Crothers, has been thinking about the apocalypse. Specifically he has been thinking about how the Old Library’s collections might be used to draw links between theological, poetic and science-fictional visions of the end of the world, and how the work of the Johnian authors Douglas Adams, Fred Hoyle and Hugh Sykes Davies might function as a linking thread.

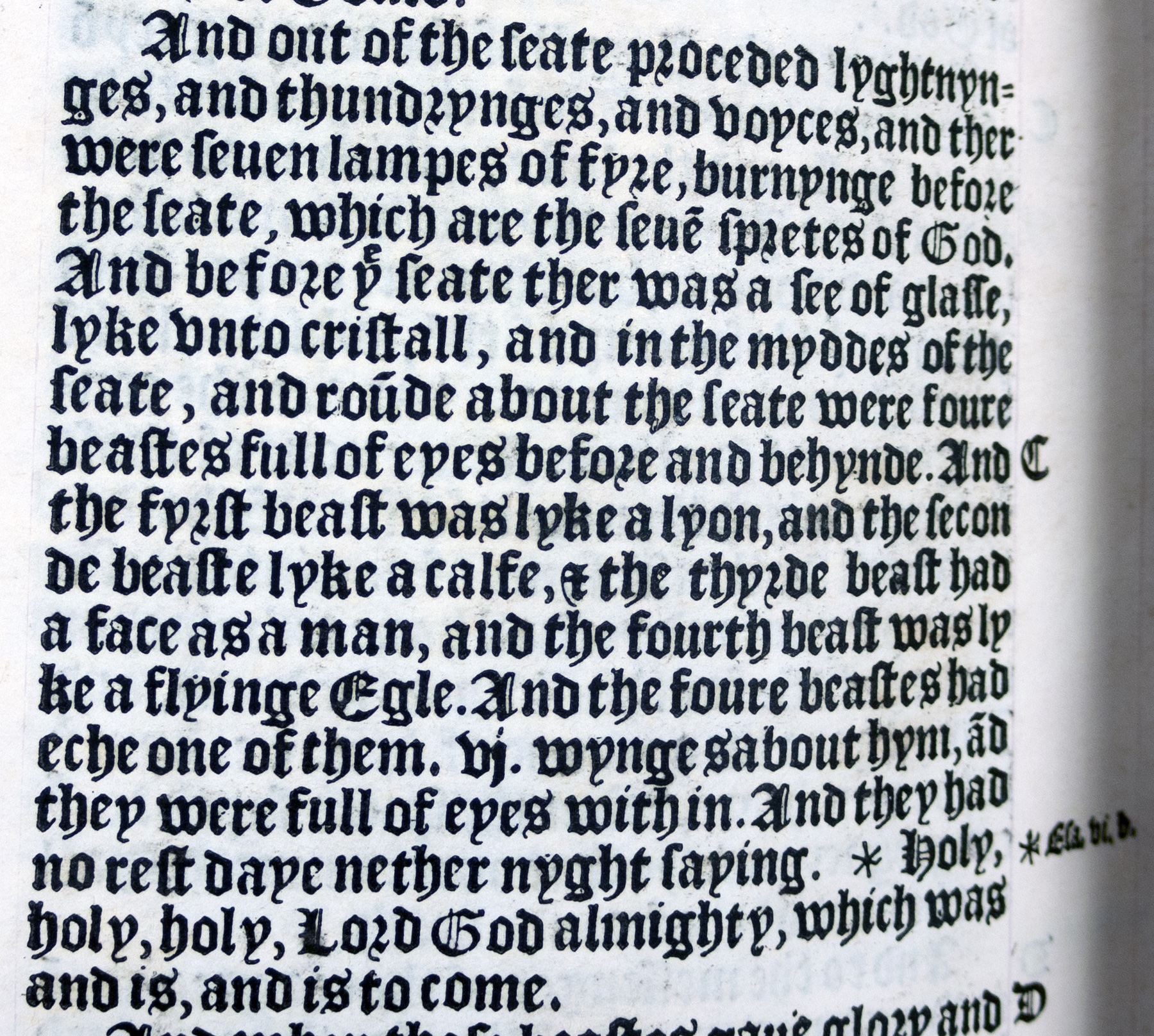

In Revelation 4:7, four creatures are described as surrounding the throne of God. The verse is pictured above as it appears in the College’s (formerly Thomas Cromwell’s) copy of the Great Bible, the first official Bible in English; it reads as follows.

And the fyrst beast was lyke a lyon, and the seconde beaste lyke a calfe, & the thyrde beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was lyke a flyinge Egle.

The eagle represents St John the Evangelist (once credited as the author of Revelation), while the lion is Matthew, the calf or ox Luke, and the man Mark. The four figures previously appeared as a group in the Old Testament book of Ezekiel, to which the Revelation passage likely alludes; this illuminated ‘E’ from a 13th-century manuscript Bible depicts Ezekiel asleep beneath the envisioned creatures.

St John is frequently depicted in the company of his eagle, including in the book of hours once owned by Lady Margaret Beaufort, founder of the College.

St John's, reasonably enough, does not explicitly associate itself with the end of the world very often. But the connection is there, and is anyway less tenuous than some of those drawn below.

Douglas Adams and apocalyptic beasts

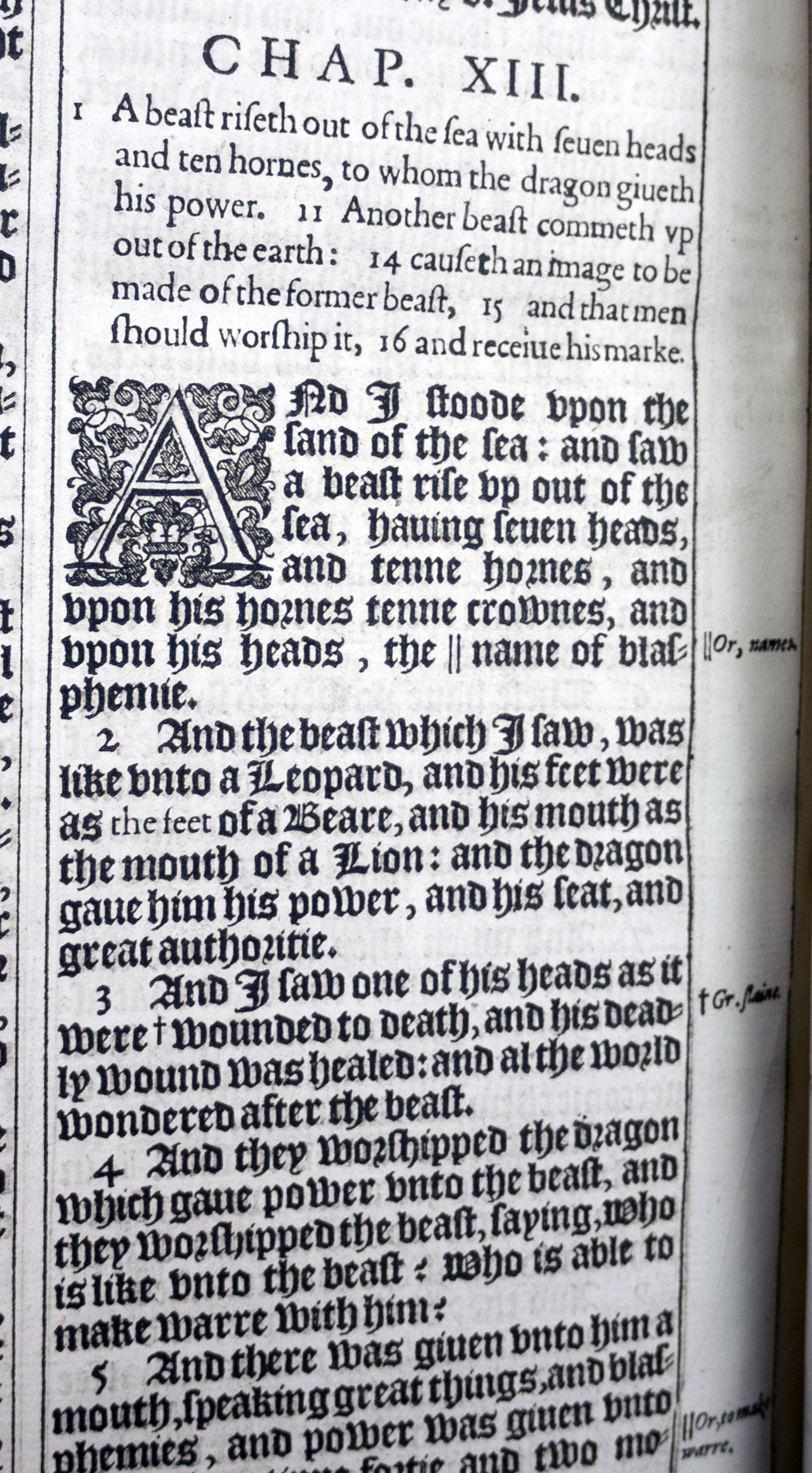

Other beasts feature in the visions of Revelation, among them a beast of the earth and, as described in Revelation 13:1-2, a beast of the sea.

This image is from the Library's copy of the 1611 King James Version of the Bible.

And I stoode upon the land of the sea: and saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having seven heads, and tenne hornes, and upon his hornes tenne crownes, and upon his heads, the name of blasphemie. And the beaste which I saw, was like unto a Leopard, and his feet were as the feet of a Beare, and his mouth as the mouth of a Lion: and the Dragon gave him his power, and his seat, and great authoritie.

This beast makes appearances in the Library's medieval manuscripts, as below.

St John and his eagle appear in the second of the above images.

Douglas Adams associated a different sort of beast with the end of all things in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (whose opening sequence, in its various incarnations as a radio serial, a novel sequence, a television series and a feature film, culminates in Earth being destroyed to make way for a hyperspace bypass). The second Hitchhiker’s novel is titled The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, the restaurant in question being Milliways. Here, diners can travel from various points in time to witness the Gnab Gib: the Big Bang in reverse; the universe’s final moments. And the beast the characters encounter might not be on a Biblical scale of terror, but it is a disconcerting presence nonetheless.

The Ameglian Major Cow, the Dish of the Day, is a living creature that is very keen on being eaten, and happily offers parts of itself to the uncomfortable diners. Among the artifacts included in the Douglas Adams collection is a model of the Cow by Susan Moore, a designer who worked on the Hitchhiker’s television series.

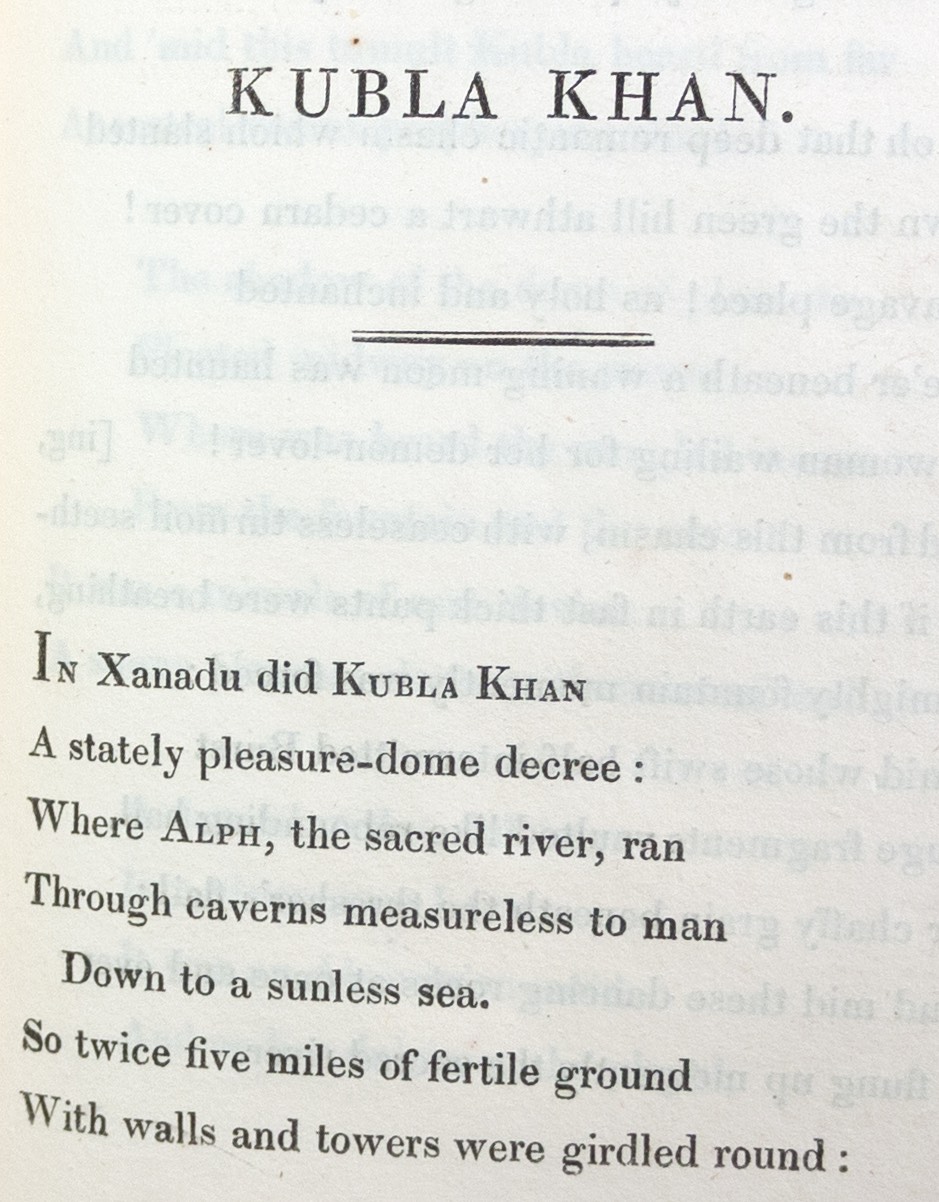

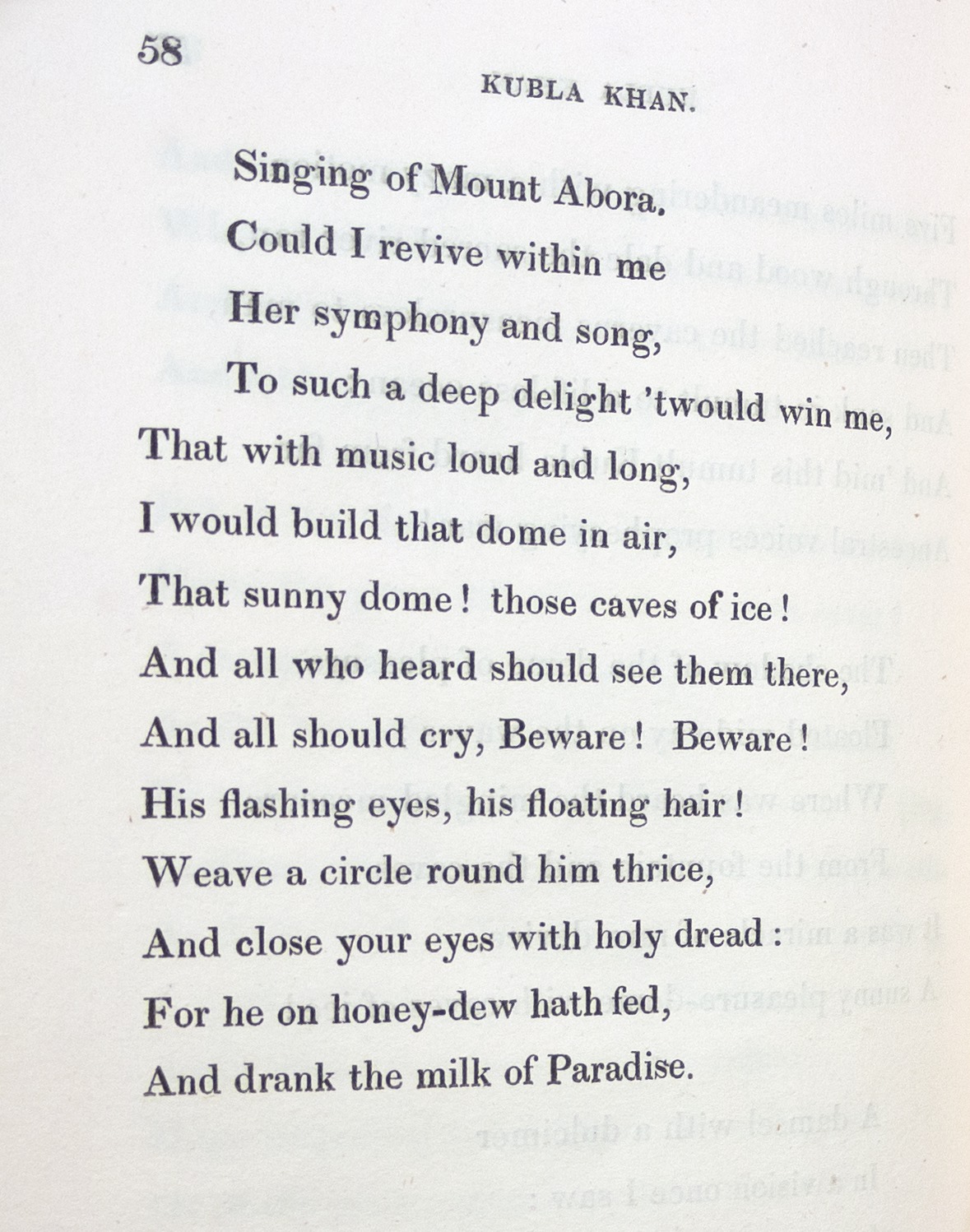

The end of the world – or rather the undoing of the origins of life on Earth – is also the subject of Adams's Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, and spoiler-averse readers who are unfamiliar with that tightly plotted novel might wish to skip to the next section of the exhibition at this point. Adams makes use of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem ‘Kubla Khan’: Coleridge claimed that the composition of the poem, subtitled ‘Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment’, was interrupted by a visitor from Porlock, such that his ‘vision’ was never completed. Here are the beginning and ending of the poem, from an 1816 first-edition printing.

In the world of Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Coleridge was not interrupted, and therefore wrote a longer poem. But: the vision was placed in the poet’s mind by an alien ghost seeking to undo the mistake that initiated life on Earth; in order to save humanity, Dirk Gently and associates engage in some light time travel in order to interrupt the poet and prevent ‘Kubla Khan’ being completed. (It all makes more sense at novel length.) The fictional ‘complete’ version of Coleridge’s poem is read early in the novel at a dinner at St Cedd’s College, Cambridge, which Adams modelled in part on St John’s; included in Adams’s papers is his extension of ‘Kubla Khan’, credited to ‘Samuel Taylor Coleridge-ish. 1797-1987’. A couple of excerpts follow.

It is war that brings about this great loss, in Adams's version: 'He watched his people die like cattle | Amidst the slaughter of the battle', and these are not cattle that want to be killed. Much of Adams's comedy is underpinned by a tragic sensibility, one that laments humanity's gratuitous wreaking of destruction upon itself.

Fred Hoyle and heavenly bodies

The main protagonist of the Hitchhiker’s books is named Arthur Dent. While Adams denied that this was conscious, it has been suggested that the name is borrowed from the author of the 1601 religious text The Plaine Mans Path-way to Heaven. While the Library of St John’s sadly does not hold a copy of Dent’s book, there are a number of depictions of heaven, one of the most compelling and complex being offered in Edward Benlowes’s devotional epic Theophila.

Here Abraham, David, and Daniel stand,

Luke, Judah, Moses, in whose Hand

The Law is held; The Virgins see,

Martyrs, Apostles, Hierarchy:

An Angell tends with Message down:

By Triangle, part drawn, is shown

The TRINITY, whose mysteries

No Mortalls Knowledge can comprise.

God is a precise geometric abstraction among the more naturalistic depictions of humans and angels; and through being 'part drawn' the shape is obscured, kept at a remove from human understanding.

The Johnian astrophysicist Fred Hoyle deployed similar alienation in depicting the titular entity of his novel The Black Cloud. The sentient cloud enters the solar system and causes chaos and suffering when it passes between the sun and Earth; on realising that the planet is inhabited by sentient beings, the cloud lets light through, and engages in communication with humanity.

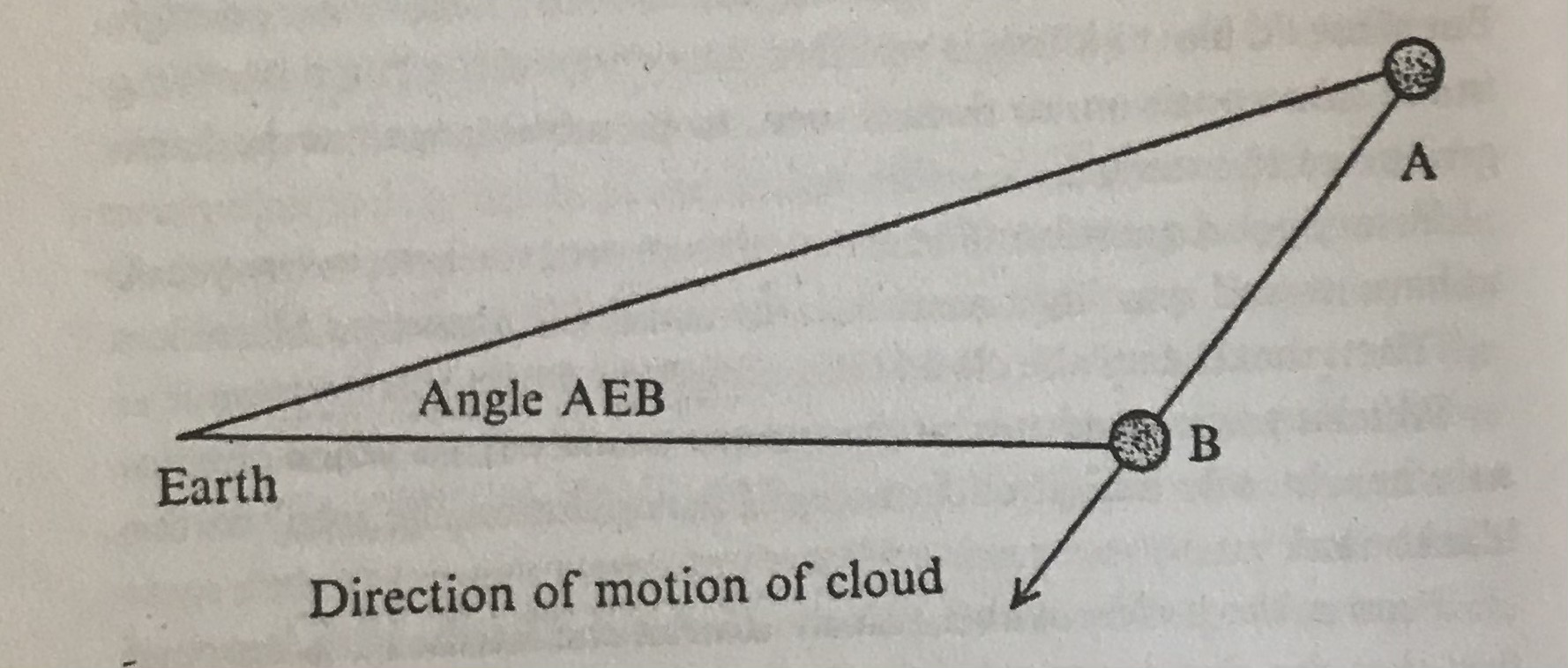

The cloud's account of having always existed seems to disprove the Big Bang (a term that Hoyle, famously, coined for a theory that he did not support); and its godlike relationship to humans is subtly reinforced by one of the diagrams with which the book's scientists conduct their investigations.

And late in the novel the following exchange occurs.

'You know in a way this is remarkably like some of the ideas of the Greeks. They thought of Jupiter as travelling in a black cloud and hurling thunderbolts. Really that's pretty much what we've got.

'It's a bit odd, isn't it? As long as it doesn't end in a Greek tragedy for us.'

The tragedy was nearer than anyone supposed, however.

By virtue of obscuring, clouds hold the promise of revelation, and below are two images from one of the College's medieval manuscripts in which God, in different forms, emerges from a cloud.

In the first of these, God presents a mirror, those looking to the heavens being asked to reflect upon themselves; in Hoyle's novel, nuclear weapons fired at the cloud are rebuffed, and redirected to precisely their points of origin. And in the second image, a depiction of Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends as a dove: a symbol with connotations of the Old Testament flood, an apocalyptic trial run.

Hugh Sykes Davies and the extinction forecast

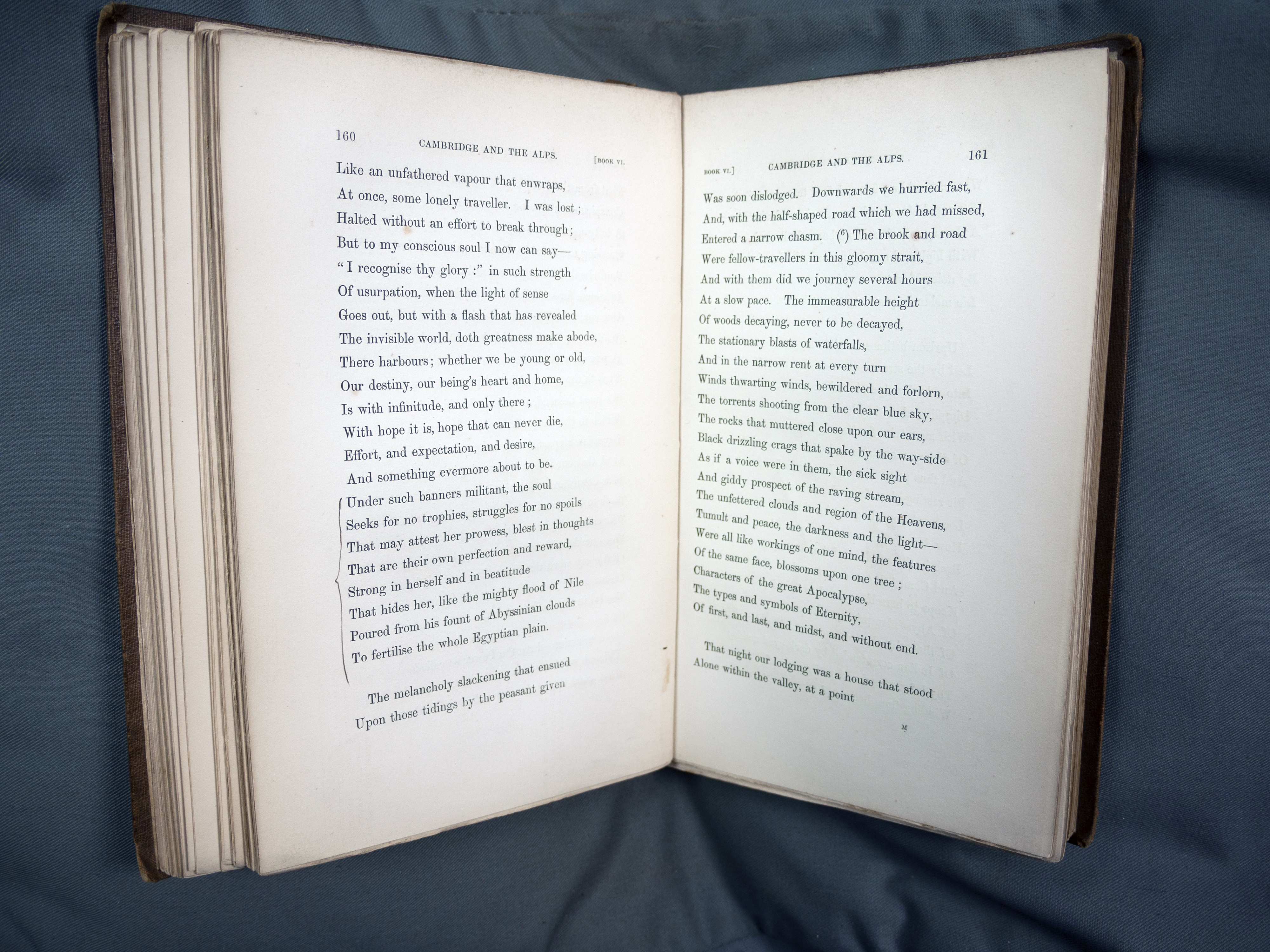

The Johnian poet William Wordsworth wandered lonely, of course, as a cloud, but clouds also have a role in a portion of his autobiographical poem The Prelude, in his description of traversing Switzerland’s Simplon Pass.

—Brook and road

Were fellow-travellers in this gloomy Pass,

And with them did we journey several hours

At a slow step. The immeasurable height

Of woods decaying, never to be decayed,

The stationary blasts of waterfalls,

And in the narrow rent, at every turn,

Winds thwarting winds bewildered and forlorn,

The torrents shooting from the clear blue sky,

The rocks that muttered close upon our ears,

Black drizzling crags that spake by the wayside

As if a voice were in them, the sick sight

And giddy prospect of the raving stream,

The unfettered clouds and region of the heavens,

Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light—

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree,

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first and last, and midst, and without end.

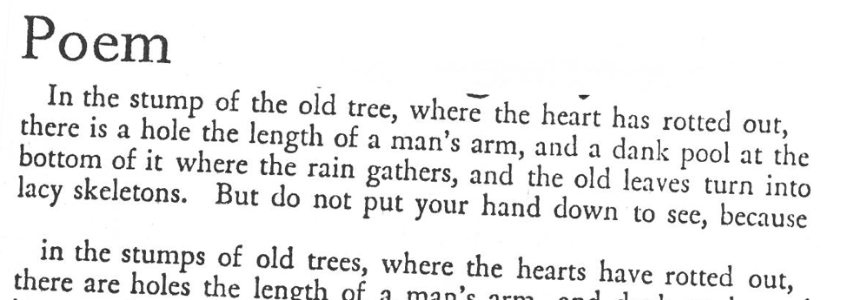

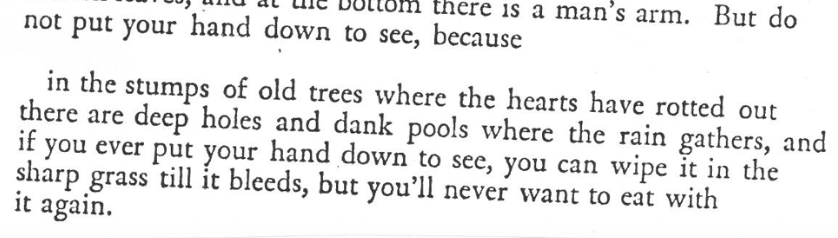

Wordsworth was the subject of Hugh Sykes Davies’s final book, published posthumously: Wordsworth and the Worth of Words. Davies was a fellow of St John’s, and as well as authoring science fiction novels (Full Fathom Five is about submarines, and The Papers of Andrew Melmoth is about rats) he was a poet, associated with the mid-20th century Apocalyptic movement. Among his significant contributions to British poetry is a 1936 poem called 'Poem'. Excerpts from the poem as it appears in Davies's papers follow; the full poem can be read via Jacket.

The initial singular 'tree' might be taken as a Genesis/Crucifixion image, but the plural 'trees' also suggest that this is not a spiritual apocalypse but an environmental one; one in which plantlife and humanity are reduced to 'stumps', and in which the consumer's bleeding hand is arguably linked with forest wasted through agriculture, trees cleared to make way for 'grass'. ('[W]here the hearts have rotted out': the hearts of the trees, or the hearts of human beings?)

The poem might be appetisingly paired with this manuscript image depicting Hercules, Theseus and Pirithous at the entrance to the underworld.

There is a tree, and a hole; and there is fire, and the underworld is something of a black cloud against the surroundings. Clouds shadow a later work by Davies: a poem called 'Scales of Disaster', which pertains to the prospect of an apocalypse he would not have envisioned in the 1930s, namely a nuclear one.

‘The Scales of Disaster’ is represented in Davies's papers by a file containing various drafts and revisions, including manuscript edits to the version published in Heckler in 1982. Inspired by the beauty its author found in the Beaufort scale (which does not pertain to Lady Margaret but to wind strength), the poem riffs on the stages of the Beaufort scale, those of the earthquake measure the Richter scale, and the increments of another scale pertaining to 'the final disasters'.

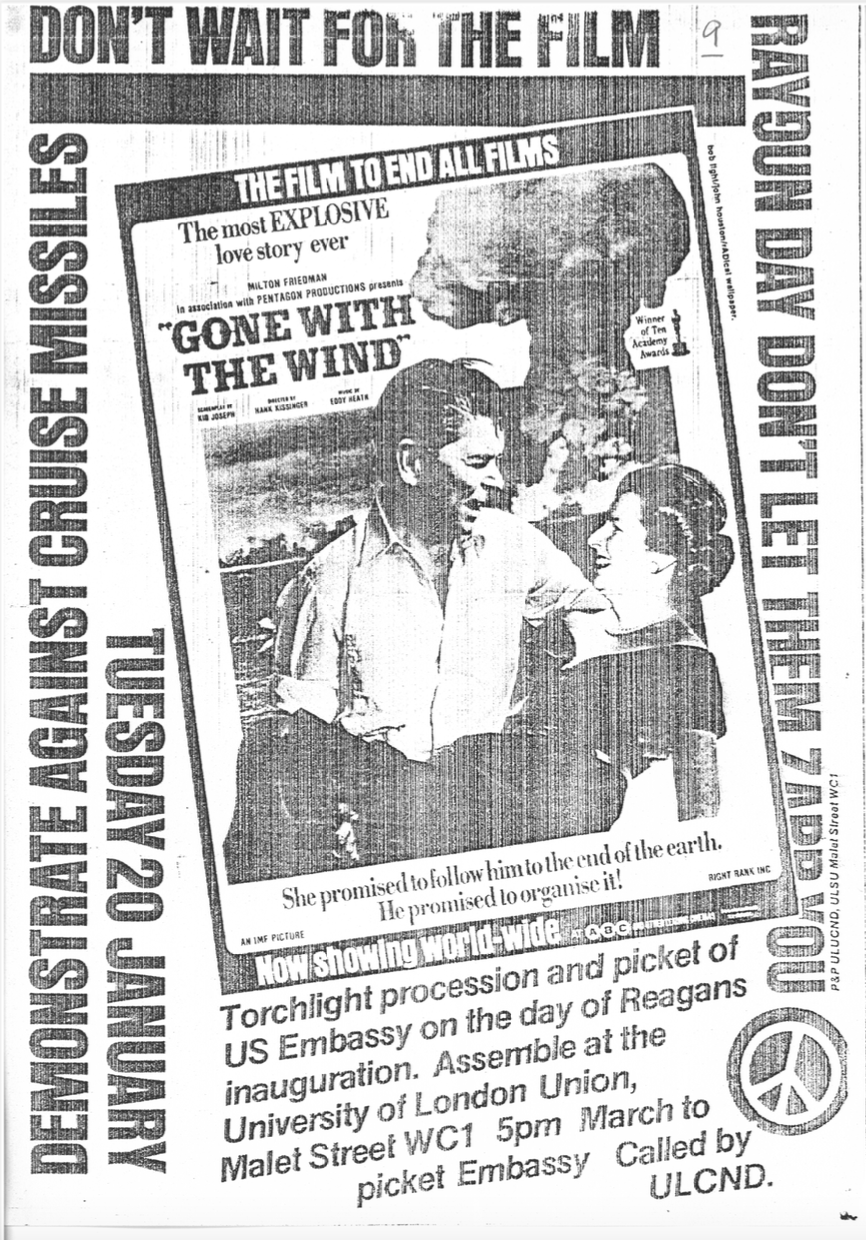

A bare-branched tree illustrates the published poem. In an introductory note, Davies says: 'I shall regret writing this if it is reduced to a merely political statement.' This is entirely reasonable, but those who are keen for evidence of the political context will note that among the documents relating to the poem is a photocopied flyer promoting a protest by the University of London wing of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

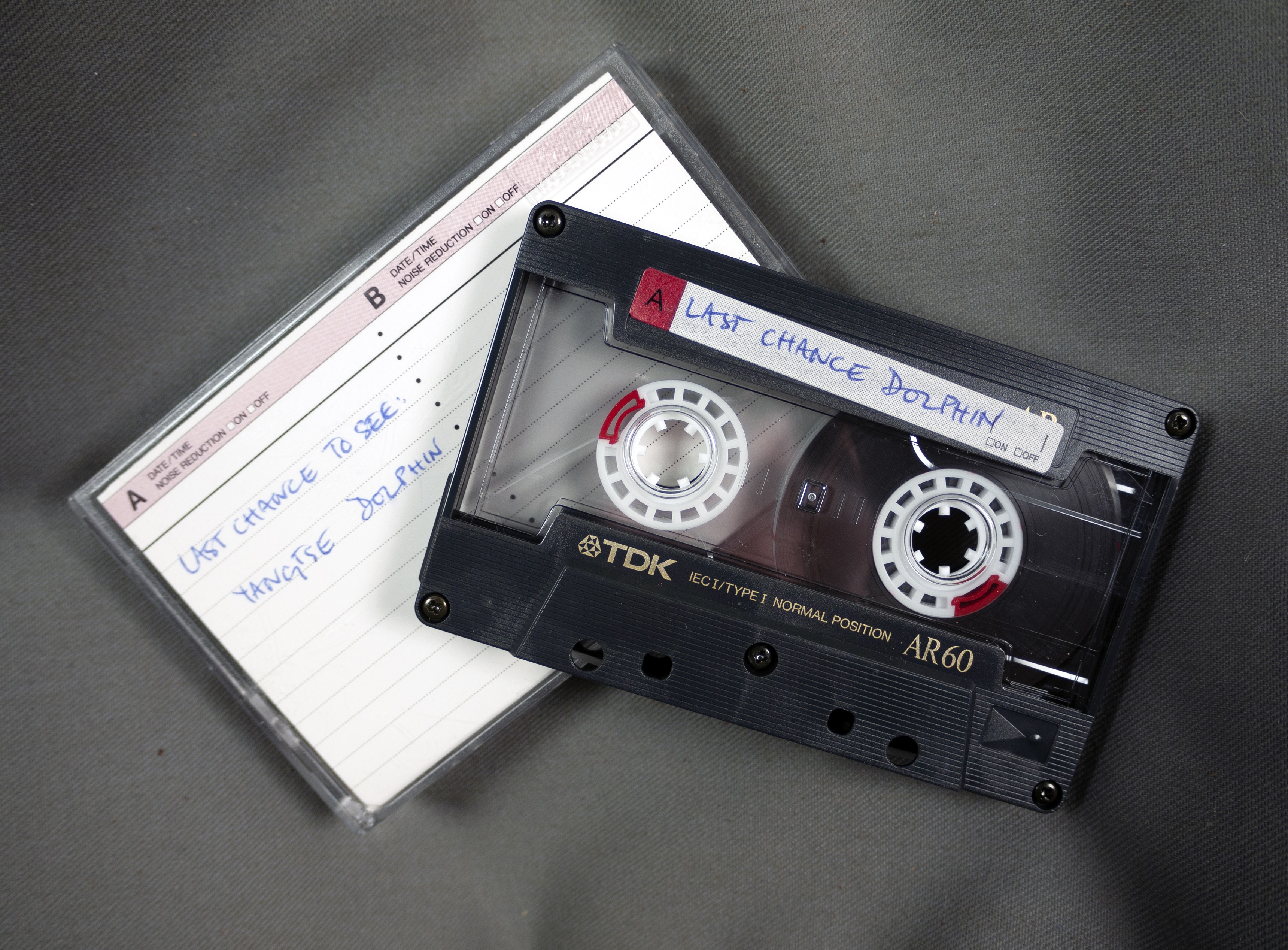

‘The Scales of Disaster’ is subtitled ‘Elegy for an Endangered Species’, which brings the exhibition back in its closing stages to Douglas Adams, whose 1990 book Last Chance to See explores various endangered species. These include the kakapo; the Komodo dragon; and the baiji, or Yangtze river dolphin, which is now believed to be extinct.

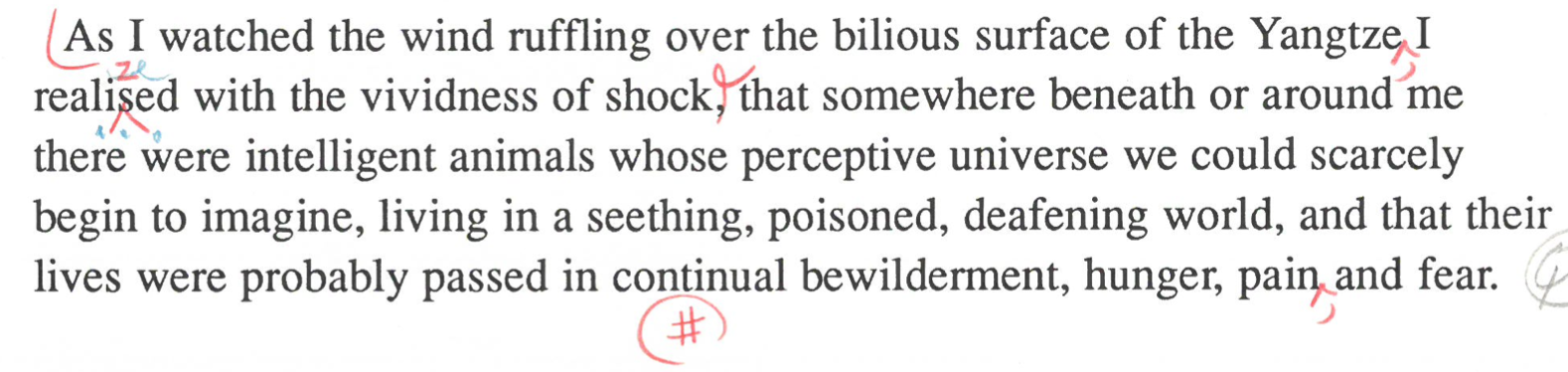

The fragility of audio cassettes means that we have yet to listen to, and determine the contents of, tapes such as that pictured above; the hope is that the audio material in the Adams collection will eventually be digitised. But for now there is something appropriate about the dolphin tape remaining silent. Adams describes how the human presence on the Yangtze has turned the dirty brown water into 'a sustained shrieking blast of pure white noise, in which nothing could be distinguished at all'. For a near-blind species dependent upon echolocation, this is, or was, a hellish situation. White noise; black clouds.

In Adams's Hitchhiker's books, dolphins are able to escape the destruction of Earth and bid goodbye to near-eradicated humanity (whom they did attempt, in vain, to warn) with a cheery 'So long, and thanks for all the fish'; but outside of fiction, the 'seething, poisoned, deafening world' humanity created for the Yangtze river dolphin aligns all too well with the surreal nuclear apocalypse envisioned by Davies, and might indeed have meant the apocalypse as far as that species was concerned. The world hasn't ended; and yet worlds end all the time, and the implications are not best ignored.