Möchten Sie Deutsch lernen…?

Learning a foreign language, and having the resources to do so, is something we now take for granted. The variety of ‘teach yourself’ books and audio-visual materials is so vast that it can be difficult to know where to start. But inevitably there must have been a starting point, and for speakers of English wishing to learn German it can be traced to The High Dutch Minerva, published in 1680. (The term High Dutch was historically used to refer to High German as opposed to Low German or Dutch, which had undergone the Second Sound Shift.)

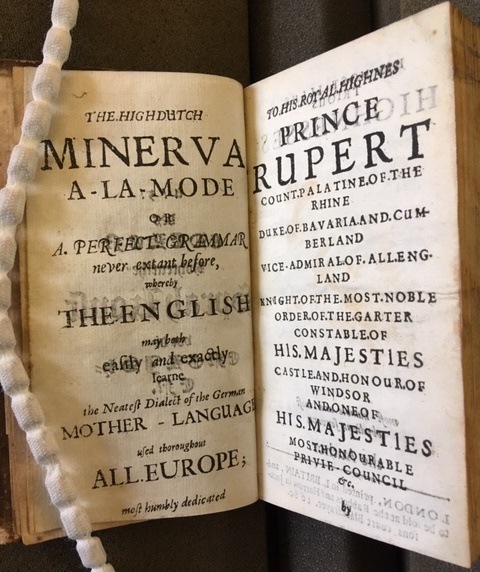

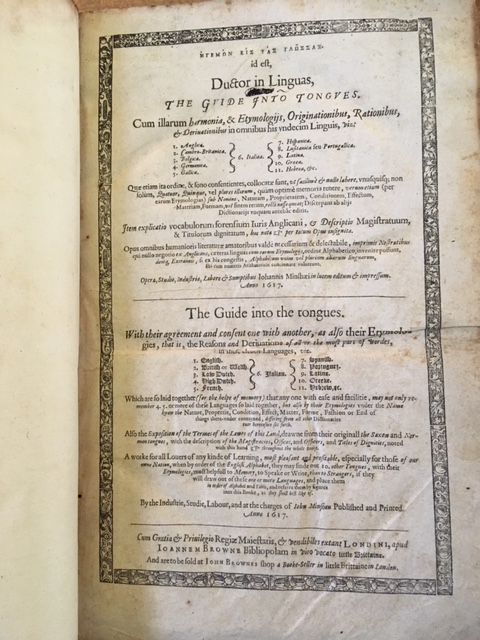

The book was first published under the full title of: The High Dutch Minerva A-La-Mode, Or, A Perfect Grammar Never Extant Before, Whereby the English May Both Easily and Exactly Learne the Neatest Dialect of the German Mother-language Used Thoroughout All Europe. Although published anonymously, it has been established that the author was in fact Martin Aedler, a German scholar and linguist who later taught Hebrew at the University of Cambridge. Aedler moved to England in 1677 and remained there until his death in 1724. Prior to the publication of the High Dutch Minerva, interest in learning the German language in England had been minimal, with other European languages and Latin taking priority. In 1617 John Minsheu’s The Guide into Tongues was published, in which German was included alongside ten other languages. However, although substantial in size, this work was essentially a dictionary containing translations of single words, and so its function as a language-learning aid was limited.

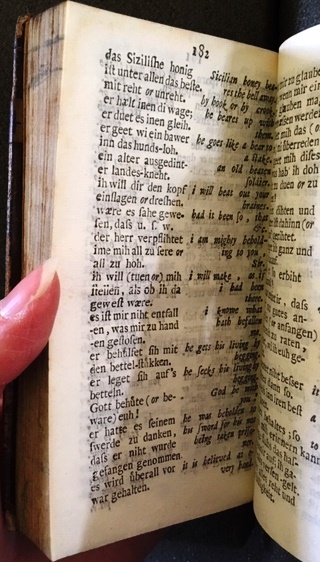

The content of the High Dutch Minerva is divided into three sections: ‘Grammatologia’ (‘handling of letters and symbols’), ‘Etymologia’ (‘words considered by themselves without construction’), and ‘Orthologia and Idiomatologia’ (‘the Art how to connect Words in writing of speaking good and true Sense’). Aedler was of the opinion that the underlying grammatical principles of language were innate, so a section containing dialogue would be superfluous to the learned reader familiar with English and possibly Latin. This theory was unusual at the time, but can now be identified as the concept of ‘universal grammar’ (a concept generally credited to Noam Chomsky).

Perhaps the most interesting section of the work is ‘Idiomatologia’, as it contains seemingly random phrases selected by Aedler which a reader might not be able to infer from prior knowledge. This includes phrases such as ‘ih will dir den kopf einslagen or dreshen / i will beat out your braines’, followed shortly by ‘der herr verpflihtet ime mih all zu sere or all zu hoh / i am mighty beholding to you, Sir’ – not something that was necessarily useful to everyone using the book for travel in Germany…

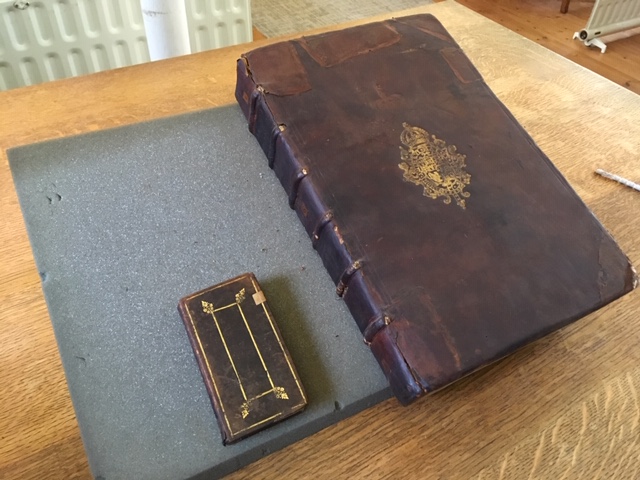

Unfortunately the High Dutch Minerva did not sell well, and Aedler was not able to repay the loan he had taken out to fund its publication. Some copies of the original print run were reissued in 1685 with the revised title Minerva: The High-Dutch Grammer – possibly as an attempt to make the title less cryptic and therefore broaden its readership. Despite this, the fact that a handful of copies have been preserved and have not been forgotten over 330 years later indicates a certain level of achievement. Indeed, the fact that it is now be considered a pioneering work in the field of German language learning in itself renders the work a success.

Further reading:

McLelland, N. (2015). German Through English Eyes : A History of Language Teaching and Learning in Britain 1500-2000. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. Fremdsprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Band 15.

Van der Lubbe, F. (2007). Martin Aedler and the High Dutch Minerva. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Land GmbH. Duisberg Papers on Research in Language and Culture, Volume 68.

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed by Catherine Ascough, Library Assistant, on 1 April 2019.