‘Mary Wollstonecraft wasn’t a killjoy’ – says author of new book on the trailblazing writer

“She was both passionate and highly critical when she so chose, but she was also able to revise her views"

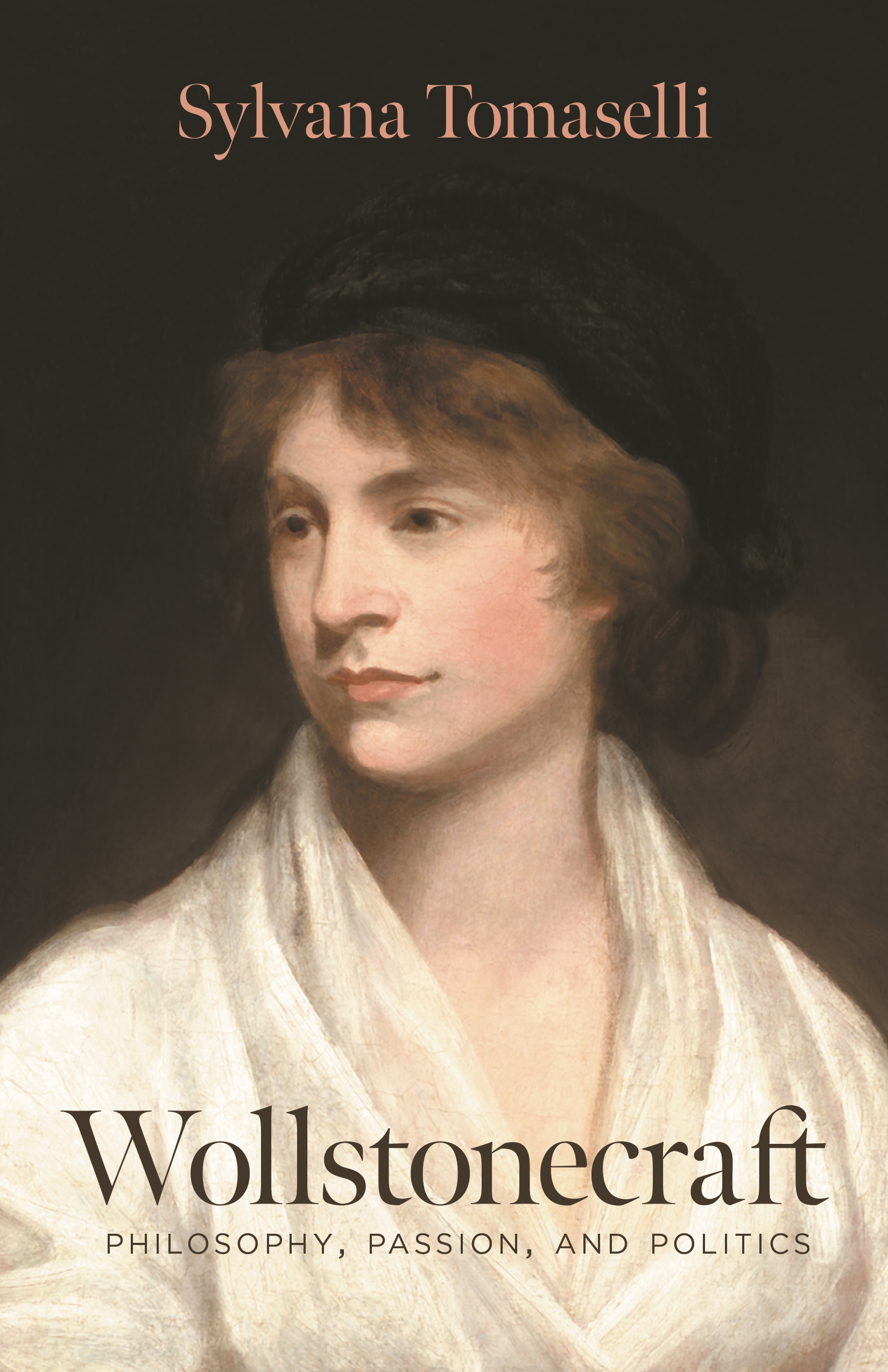

A new book by a St John’s historian paints a richly rounded picture of the writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, aiming to restore her to her rightful place as a major thinker of the 18th century.

In Mary Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics, Sylvana Tomaselli throws light on the less salient side of Wollstonecraft, known as the pioneer of English feminism – famous for her ground-breaking A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) – and mother of Frankenstein author Mary Shelley.

Sylvana Tomaselli, Sir Harry Hinsley Lecturer in History, Director of Studies in History and Human, Social and Political Sciences, and Fellow of St John’s, calls for a wider understanding of Wollstonecraft, who was an advocate for equality of men and women and a keen abolitionist of the slave trade and slavery. She was a controversial writer and fierce critic of societal norms in her own brief lifetime – she died days after childbirth, aged 38 – and the different labels attached to her today can eclipse her place in history as a leading intellectual and philosopher, argues Tomaselli. She provides a portrait of Wollstonecraft as a deep thinker and as a woman who enjoyed the pleasures of life. Having studied Wollstonecraft for many years – and edited Mary Wollstonecraft: A Vindication of the Rights of Men and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (Cambridge University Press, 2012) – Tomaselli said: “I wanted to show that she wasn’t a killjoy, always critical, which is how she can easily be seen. She liked walking, she liked nature, she liked the theatre, not least Shakespeare. I also tried to avoid labels – feminism, republicanism, liberalism, any ‘ism’ possible. These labels are an unhelpful way of approaching her life and work.”

Published in the UK on 12 January, the book echoes the format in Wollstonecraft’s collection of short essays, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. Under brief chapter titles such as ‘Painting’, ‘Music’, ‘Memory’ and ‘Property and Appearance’, Tomaselli explores not only what Wollstonecraft enjoyed and valued, but also her views on society, knowledge and the mind, human nature, and the problem of evil – and how a society based on mutual respect could fight it.

“It’s clear that she saw human beings as naturally benevolent. So I ask, if we are benevolent, what happened?” said Tomaselli. “I looked at her views about the history of society, the origins of society and what might have gone wrong such that we are in a world in which there is inequality, in which there is slavery, in which women are expected to fulfil duties for which they are singularly unprepared by society. I also provide a sketch of the world as she would have liked it to be.”

As well as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and the earlier A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), Wollstonecraft wrote a history of the French Revolution, critical reviews, translations, travel pieces, pamphlets, even novels. Tomaselli argues there has been an over-emphasis on A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in isolation from the rest of Wollstonecraft’s work. “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman doesn’t really discuss rights as much as the title might lead one to expect. Wollstonecraft came to the issue of women and their rights and their subjugation and iniquitous treatment by considering the ways in which men are treated, and very importantly, the language of slavery.”

Wollstonecraft was influential among the intellectual community in her own lifetime but, after a memoir published by her widower William Godwin – Mary Shelley’s father – revealed her unconventional lifestyle, her reputation was somewhat tarnished for nearly 200 years, until she became regarded in the 1960s as a pioneer of women’s rights and the first English feminist.

Had she lived longer, Tomaselli said, it is likely Wollstonecraft would have penned a second volume of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. “From the notes we have, it would have had less to do with rights and much more to do with philosophical issues, with the idea of beauty, the sublime, the nature of the imagination and ethics. I think that's what she would have written about, because that's what interested her – how we come to have the ideas we have, how we should think about ourselves, who we should be; these were the kinds of existential questions that preoccupied her.”

Tomaselli admires Wollstonecraft’s ‘intellectual honesty’. “There’s an openness, a self-awareness. She's both passionate and highly critical when she so chooses, but she's also able to revise her views.”

Students, readers and fans of Wollstonecraft are invited to do the same.

- Mary Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics (Princeton University Press, released 12 January 2021 in the UK) is available in hardback (RRP £25) and ebook format.

Published: 12/1/21

Back to College news