LOOKBOOK

Before the age of mass-produced paperbacks, each book that was made was a unique object. Scribes, printers, and bookbinders decorated their wares in the latest styles, while book-owners used their personal libraries to showcase their learning, their refined taste, or simply their wealth. Books were luxury goods – they were a fashion statement.

Come take a look through some truly designer books: from fine materials and decoration, to bold political statements, to the inevitable fads and knock-offs. Let’s see what’s on the runway…

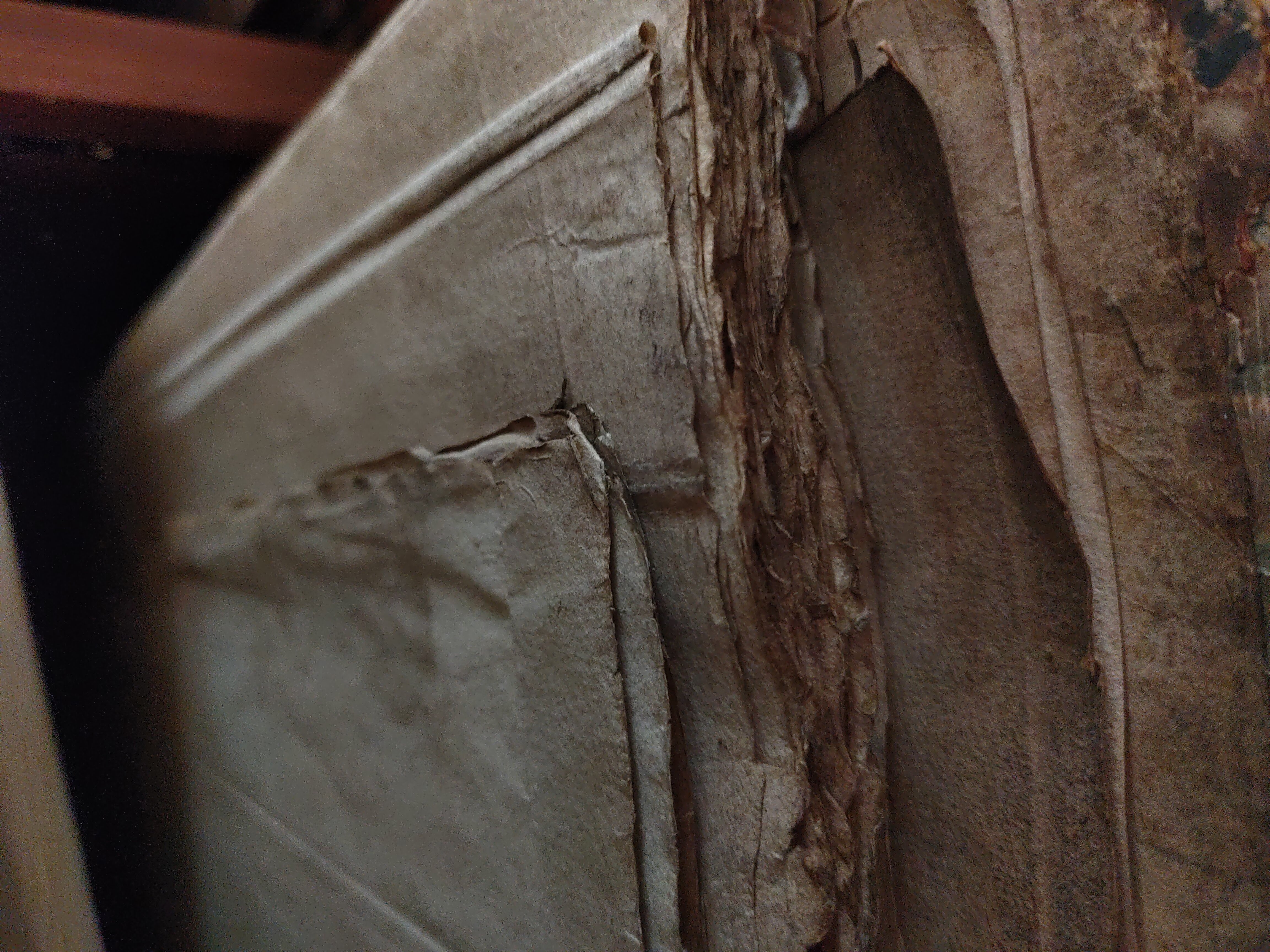

The Fabric Of A Book

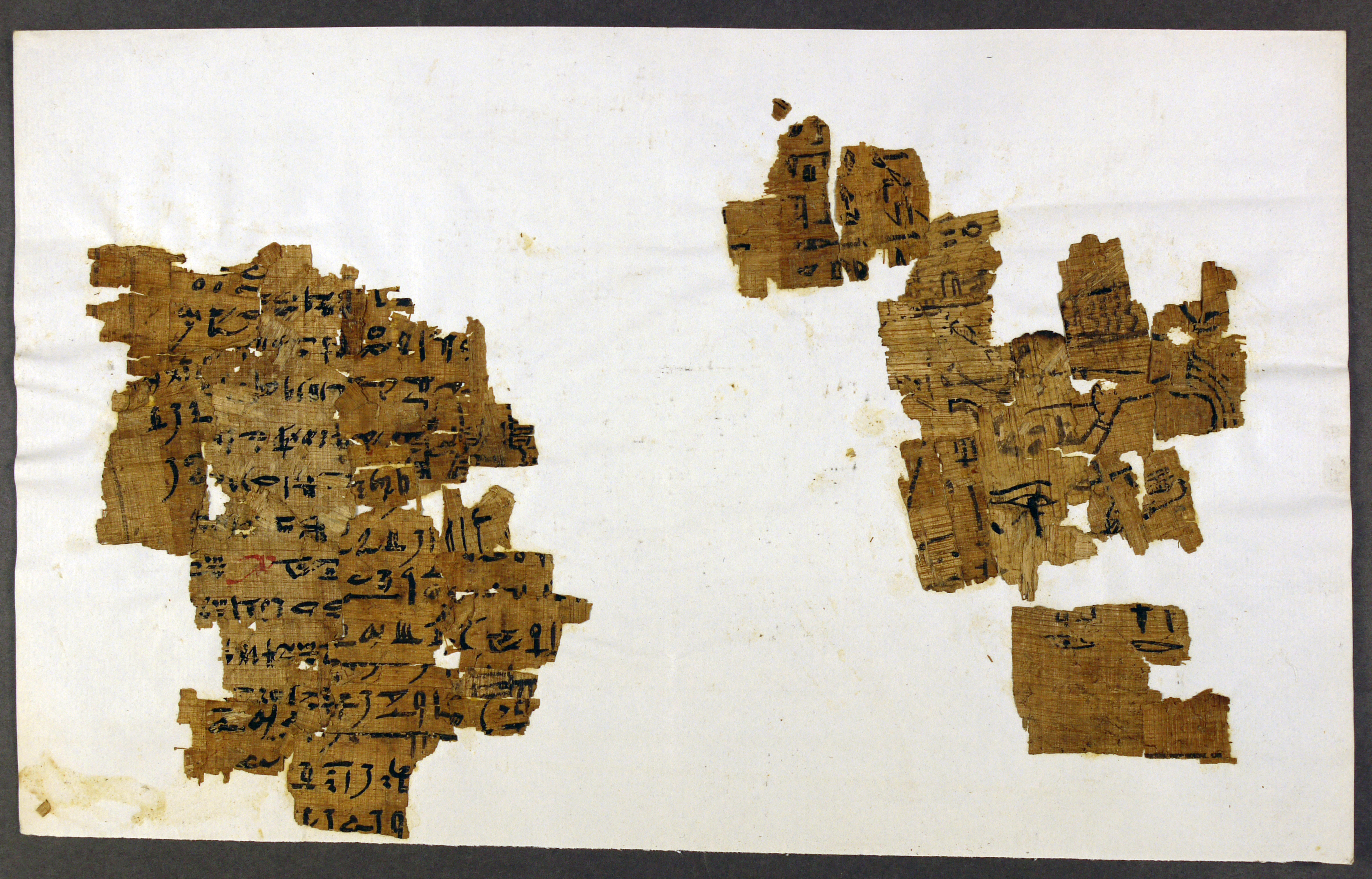

The earliest kind of ‘paper’ was made by the Ancient Egyptians, by cutting strips of the papyrus plant. They soaked the strips in water, set them down in a grid pattern, and pressed them together until they created a flat writing surface. Papyrus grew plentifully along the River Nile, which made it an obvious choice, but the material has its drawbacks – it has ridges in it from the intact plant fibres, and over time the strips become brittle and start to crack apart. Many documents and religious texts that were written on papyrus still survive, preserved by dry desert conditions, but they are usually broken into tiny fragments.

Paper as we know it started out in China, with the earliest surviving piece dating from around 179 BCE. The process was refined by Ts’ai Lun, an imperial official, in 105 CE, and his innovation gradually spread across Asia and the Middle East. The new paper was made from a mix of broken-down plant fibres and old rags, and was more flexible and durable than papyrus. The technology was brought into Italy by merchants, and with a few modifications, it gradually spread across Europe.

Initially, people were sceptical. This new kind of ‘parchment’ was more fragile, it tore easily, and it didn’t behave properly with ink. In 1145, King Roger II of Sicily decreed that all paper charters made before his reign should be copied out again on parchment, and the paper copies should be destroyed. But the new technology had its advantages: it was cheaper than using animal skins, and could be bulk-produced, and as literacy increased it became popular for note-taking, letter-writing, and business minutes. ‘Paperwork’ had been born.

The booming demand for paper brought a new difficulty: a shortage of materials. European paper was made using fibres of linen and flax. Old rope was a good source for this, and many paper mills sprang up near ports. But the finest paper required the finest fibres, which were sourced from the rag trade in discarded clothes. The very softest fibres were found in linen underwear. By the 1600s in France, demand for reading material had so far outstripped the availability of rags that the paper industry was in crisis, and multiple laws were passed to try to regulate the trade in old underwear, to save the paper mills.

In the 1700s, there were many brief fashions for using different bases for paper. Some, like wood, would be familiar to us, others less so: esparto grass, palm leaves, and seaweed all had their moments of dubious papermaking glory. Eventually, various advances in chemical technology allowed wood to be pulped and then treated to make paper that was brighter, stronger, and more durable. Although it has taken a lot of cutting-edge science to get to the paper we know today, the basic principles behind it would still be familiar to the Ancient Egyptians, almost five thousand years later. Here’s to the next five thousand.

Unusual Materials

Lewis Evans, The castle of Christianitie, 1568 (left) and New Testament, 1632 (right)

These rare surviving embroidered bindings probably belonged to Elizabeth I and Charles I. In the early modern world, sumptuary laws restricted the ways that people could dress, especially which fabrics they were allowed to wear. But monarchs enjoyed free rein over fashion, and these two clearly had lavish tastes in their bookbinding – Elizabeth was said to have been especially fond of velvet.

Bible, 1632

The finest materials and bindings are often reserved to honour sacred texts. This ‘most elegant Bible’ was presented to St John’s in 1647 by the then-wealthy alumnus Sir Thomas Dawes (d. 1655), a supporter of Charles I. It is bound in velvet with gilded page edges, the silver medallions representing saints and allegorical figures. It has marbled paper inside the covers, and 110 leaves of biblical illustrations.

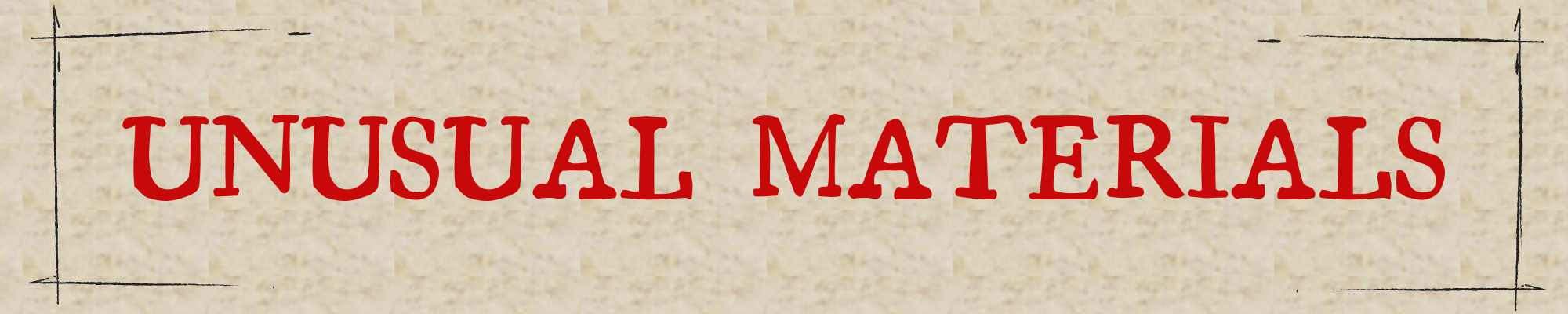

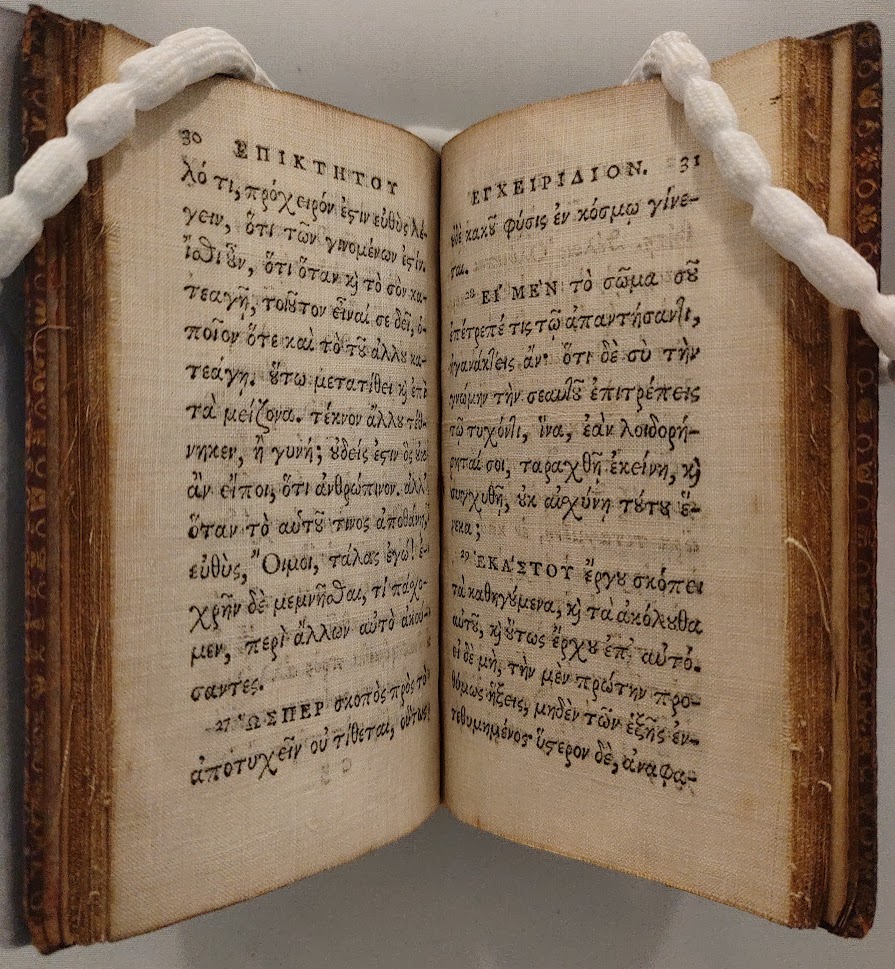

Epictetus, Encheiridion, 1748

This curious volume has been printed on linen fabric. An uncommon practice, and the fraying edges of the pages perhaps suggest a reason for that. The ancient philosopher Epictetus was very fashionable during the Enlightenment, and the Encheiridion (‘handbook’) of his ideas was widely used as a school text. The clear and accessible style also made it popular with female readers who had less access to formal education.

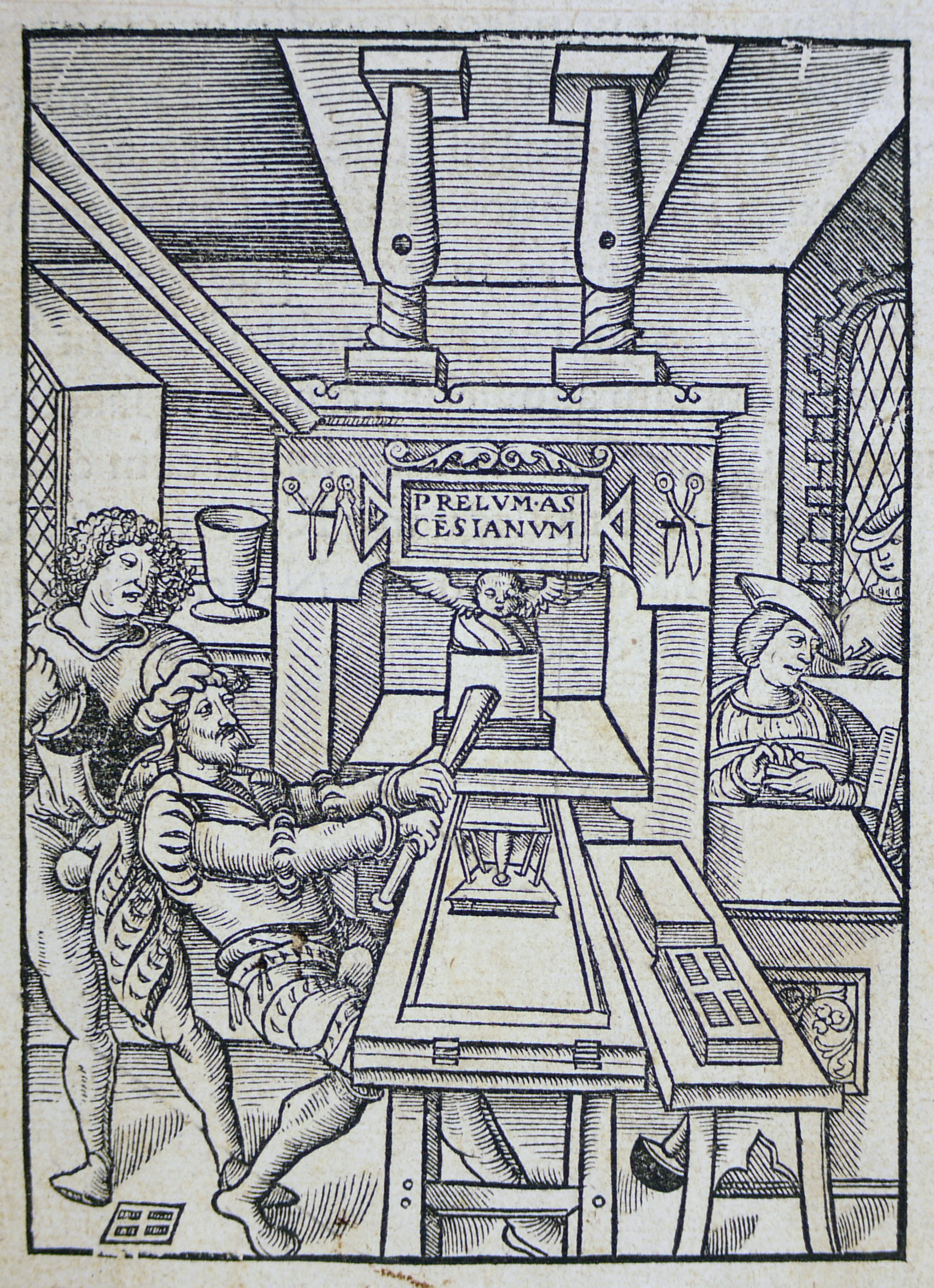

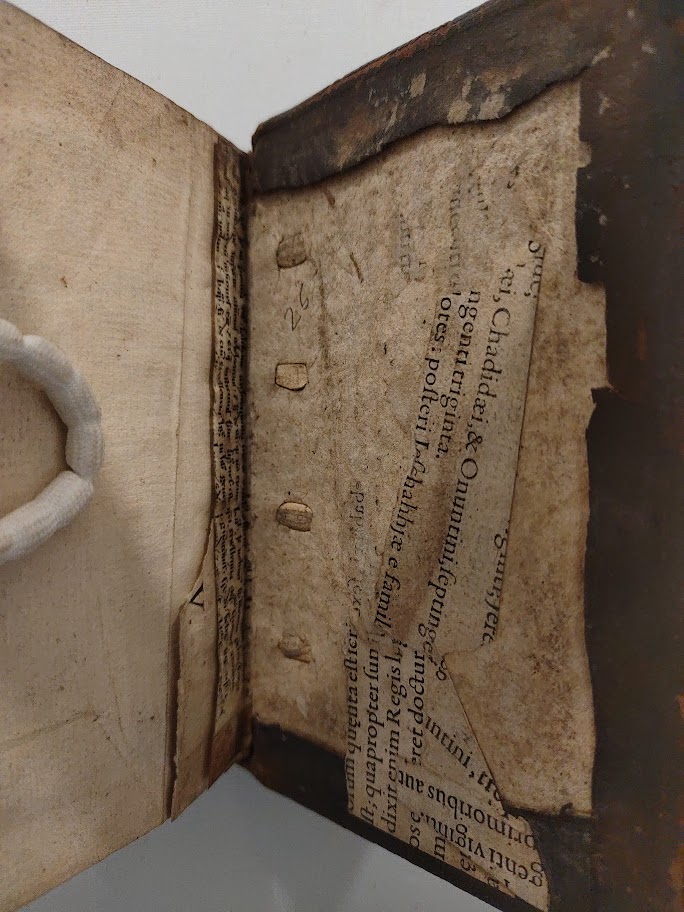

Paolo Manuzio, De legibus Romanis, 1569

This book on Roman law has been reinforced with scraps of unrelated printed ‘waste’, and even a fragment of a manuscript. Although this common fashion often hastened the destruction of older books, it ironically also kept these pieces safe in the binding, and they are now a valuable source for historians. Manuzio printed his own work, having inherited the business from his father, Aldus Manutius (c.1449–1515).

Bespoke Books

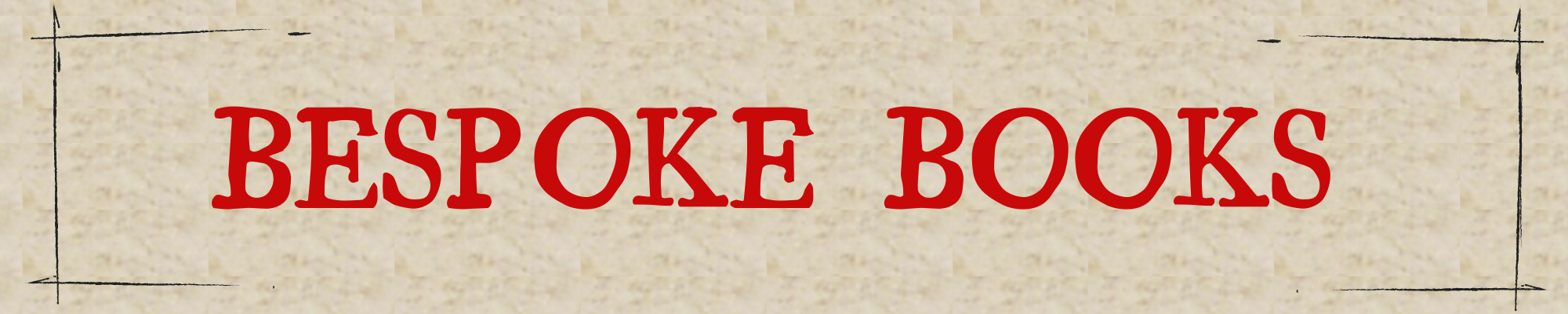

Before printing, if you wanted a book, you had to copy it out yourself. The first European centres of book production were large monasteries, where monks or nuns would work in the ‘scriptorium’ to write and copy out texts. The Rule of Saint Benedict stipulated that monks should read daily, and even though the focus was more on close analysis of a few devotional texts, the monks still needed a way to get hold of new reading material. Although they mostly focused on copying religious texts such as the Bible or the writings of the early Church Fathers, many were also happy to copy pre-Christian texts, and the Church therefore played a large part in preserving Ancient Greek and Roman culture, and keeping it in fashion for studying.

With time and resources at their disposal, the monasteries became specialist book suppliers to the outside world. It is difficult to reconstruct exactly how a scriptorium would have worked, but it is clear that there was (usually) a division of labour. Specialist workshops supplied sheets of parchment made from animal skins, often calf, which were scraped clean and stretched out to write on. A monk would then smooth the parchment further and prepare the surface, before a different monk ruled lines and copied out the text. Another monk would then ‘illuminate’ the grander manuscripts, by painting borders, elaborate initials, and illustrations, which sometimes have very little to do with the subject matter of the book. The finest books were often decorated with gold leaf.

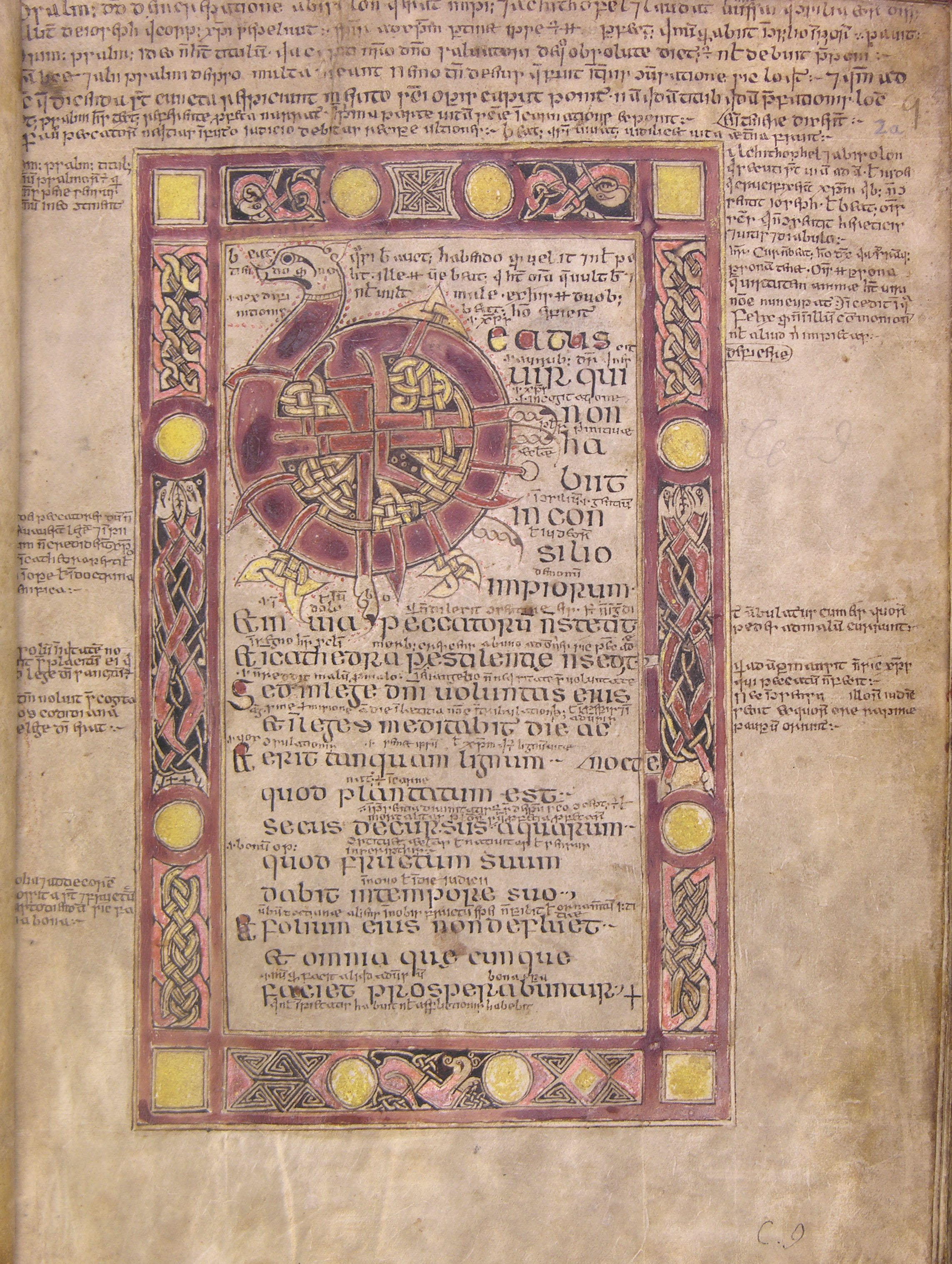

Eventually, secular scriptoria arose, where professional copyists and artists worked on commissions for wealthy patrons. The growth of universities in Europe increased demand for the works on the syllabus, and there was a thriving industry in copying out textbooks. But even after the rise of printing in the 1400s, handwritten and hand-decorated books did not entirely fall out of fashion. Bespoke adornment was still a way to set your book above your neighbour’s copy, and some wealthy patrons continued to employ artists to hand-illuminate their printed texts. In religious settings, hand-copying continued to thrive, as an act of devotion and reflection rather than a commercial enterprise.

Accessorising

Jin Guliang, Wushuang pu, 1670

This ‘Pictorial album of unique persons’ illustrates forty figures who span sixteen centuries of Chinese history. It was printed with woodblocks, each page layout having a unique block. Pictured here is Feng Dao (882–954), a government official credited with hugely improving the printing process. Although movable type was invented in China in c.1040 CE, which allowed multiple different books to be printed by rearranging the same letter blocks, the vast number of Chinese characters needed meant that it never became as popular as it later would in Europe.

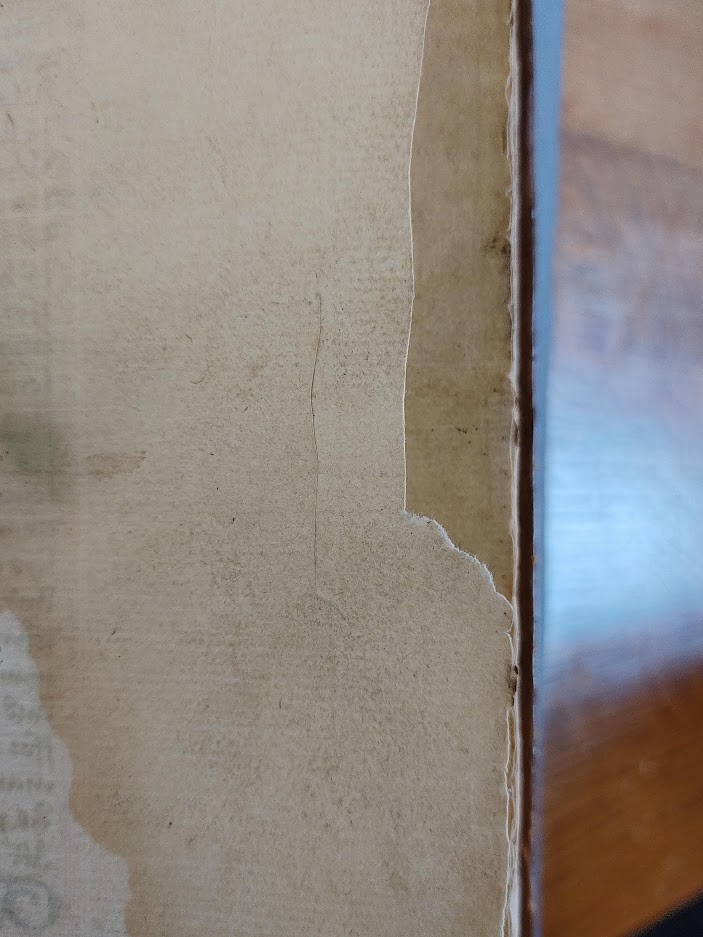

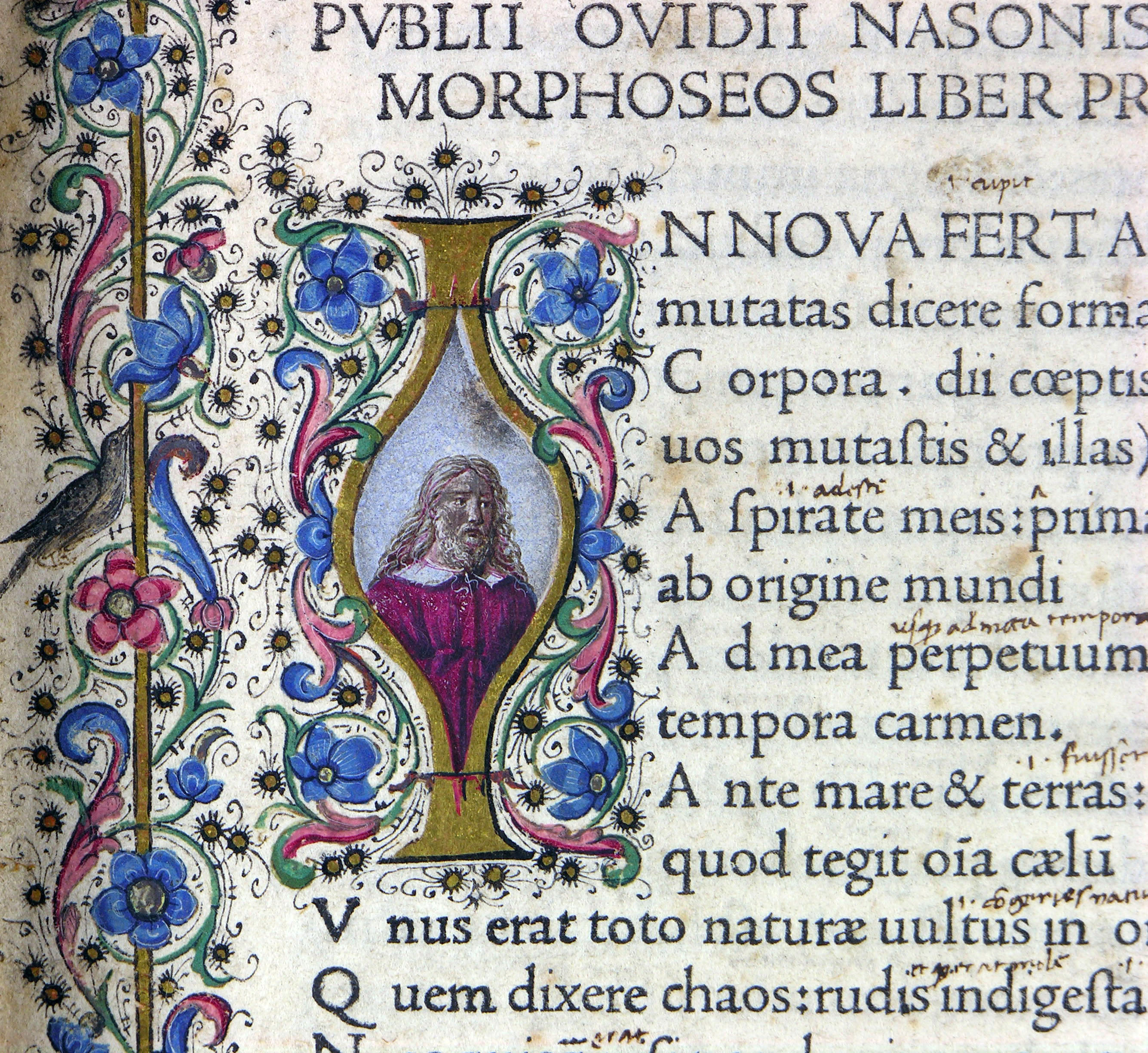

John Evelyn, The history and art of chalcography, and engraving in copper, 1769

Engraving, which emerged in Europe in the 1400s, uses incised metal plates to print pictures instead of wooden blocks. It allows for finer detail, making it popular for music, and the plates are more durable than wood. Unfortunately, it also requires a different printing method from the rest of the text, which is why illustrations are often on separate pages. It places much more pressure on the paper – here the ‘plate mark’ is clearly visible around the edge of the illustration, tangible evidence of how this book was made.

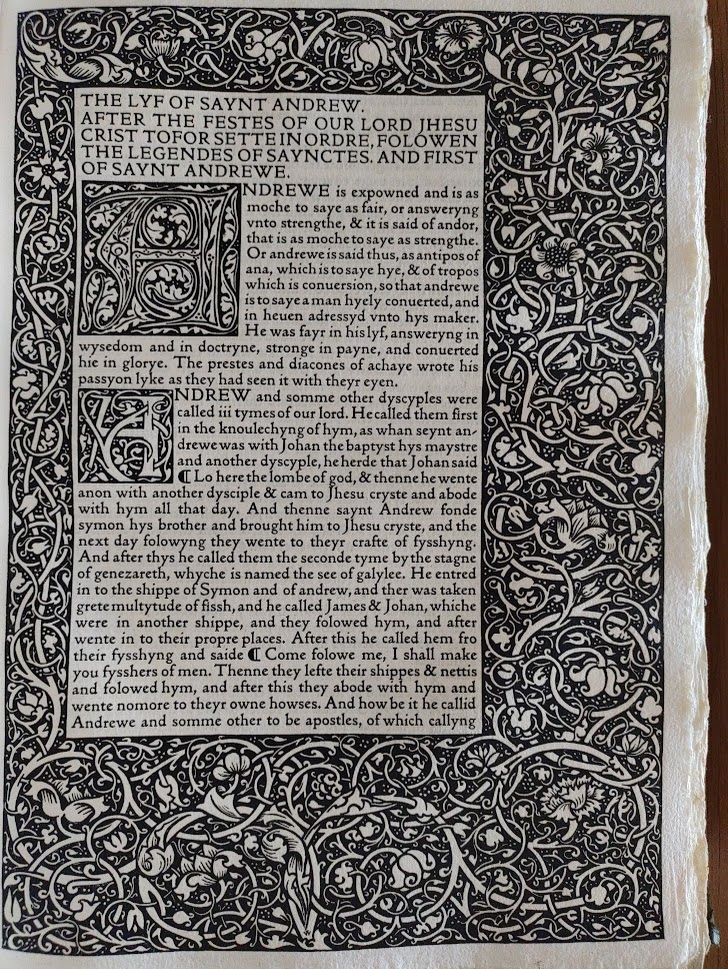

Jacobus de Voragine, The golden legend, 1892

This elaborate edition was printed by the artist William Morris (1834–1896) at his Kelmscott Press. Morris, part of the fashionable Arts and Crafts Movement, sought to recapture the beauty and skill of early book production, which he felt was under threat from increased industrialisation and more widely affordable books. The woodcut decorations here echo his nostalgia for historic printing styles. This edition follows the version made by William Caxton (c.1422–1491), which was one of the first books to be printed in English.

More Accessorising

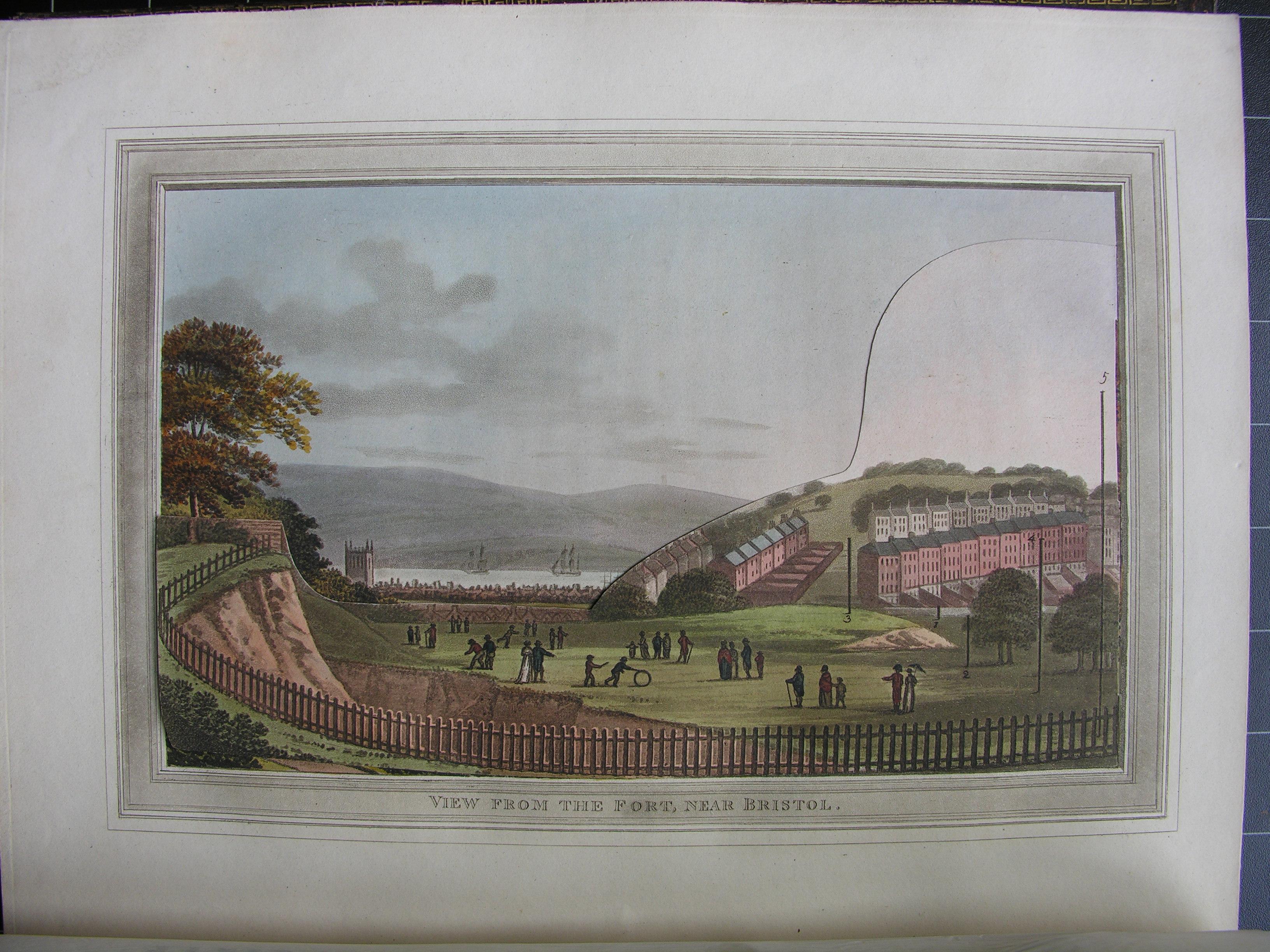

Humphry Repton, Observations on the theory and practice of landscape gardening, 1805

Repton was a pioneering landscape gardener, the successor of ‘Capability’ Brown at Hampton Court. Here he markets his work by showcasing the latest fashions in garden design. This lavish book contains unusual double illustrations – readers can lift the flaps to compare ‘before’ and ‘after’ scenes.

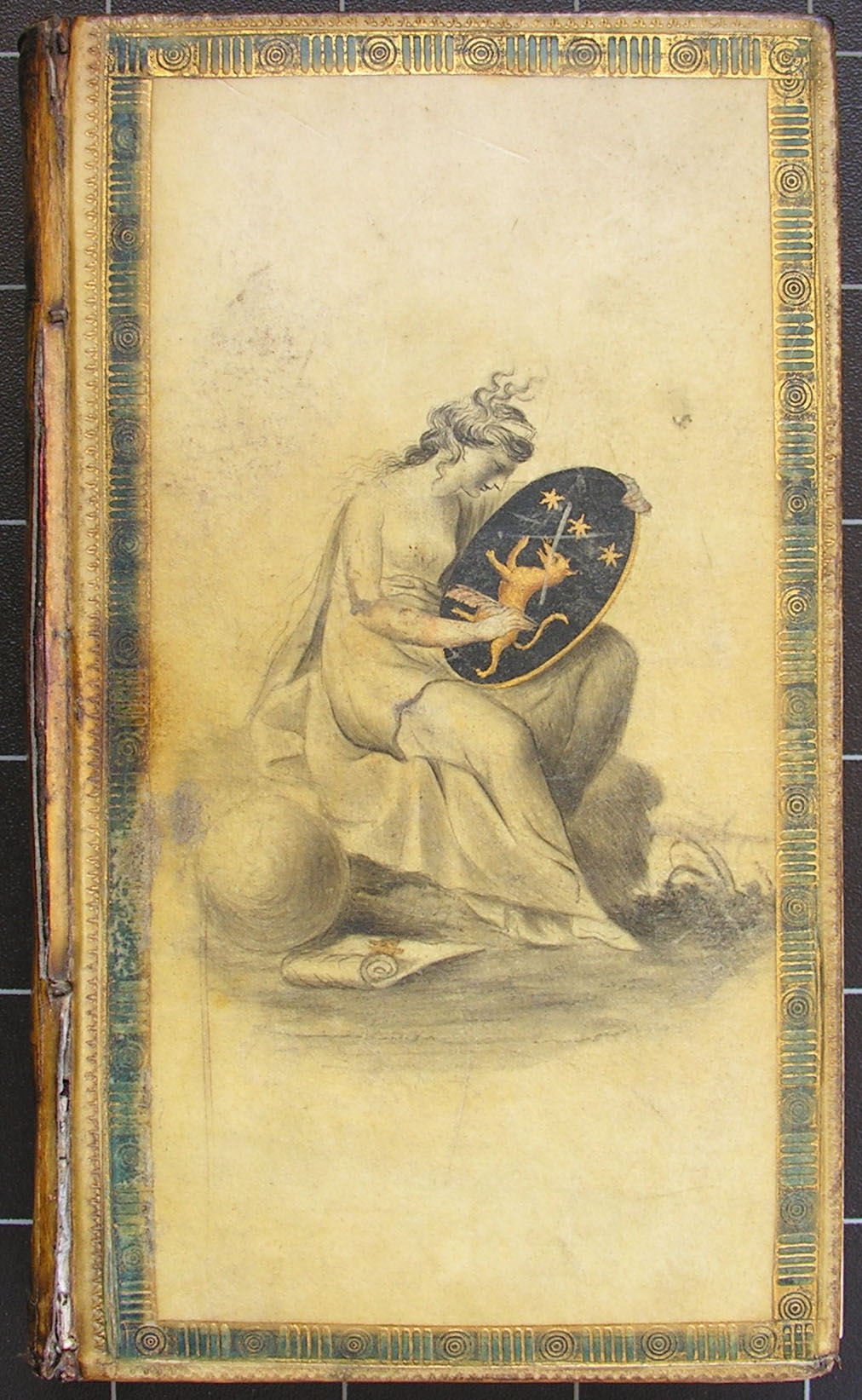

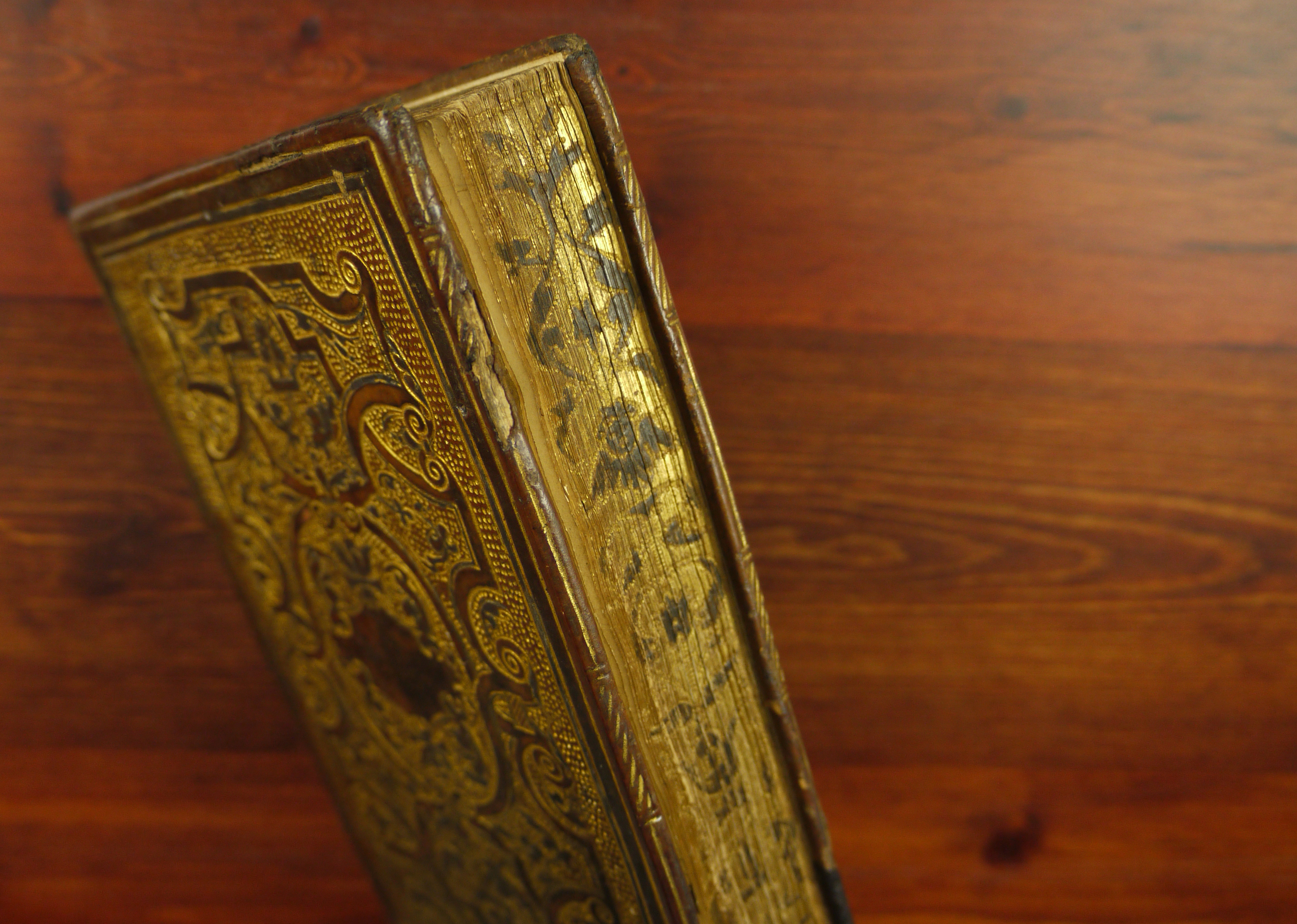

Book of common prayer, 1772

Rather than a more traditional leather binding, which were popular either ‘blind-stamped’ or decorated with gold leaf, this book is bound in painted vellum. James Edwards of Halifax (1757–1816) patented an innovative method for this, which involved painting on the back of the translucent membrane, so that when it was bound the right way, the painting would be safe from damage. Sadly, the fashion wasn’t so enduring.

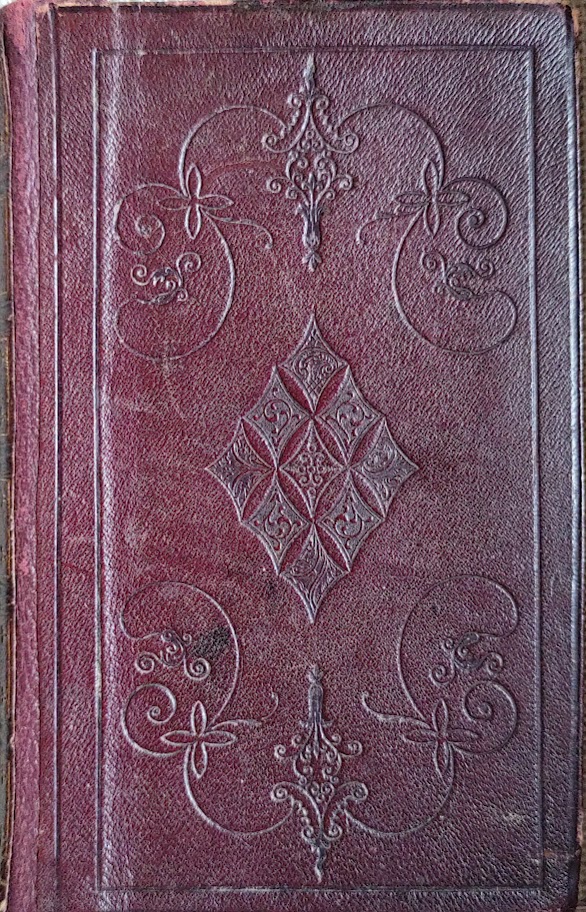

Book of hours (French), 1558

This volume, possibly bound in Lyon, emulates the favourite bookbinding style of Jean Grolier (c.1489–1565), the Treasurer-General of France, who popularised the ‘entrelac’ (interlaced) fashion. It has also been decorated by ‘gauffering’ the gilded edges – using heated pointed tools to create dotted patterns.

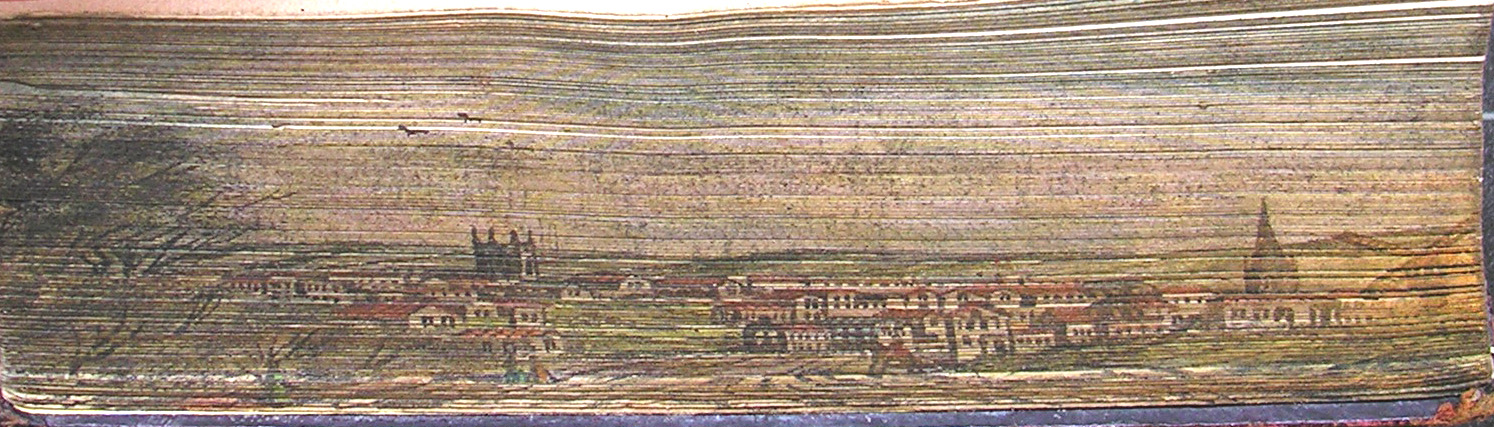

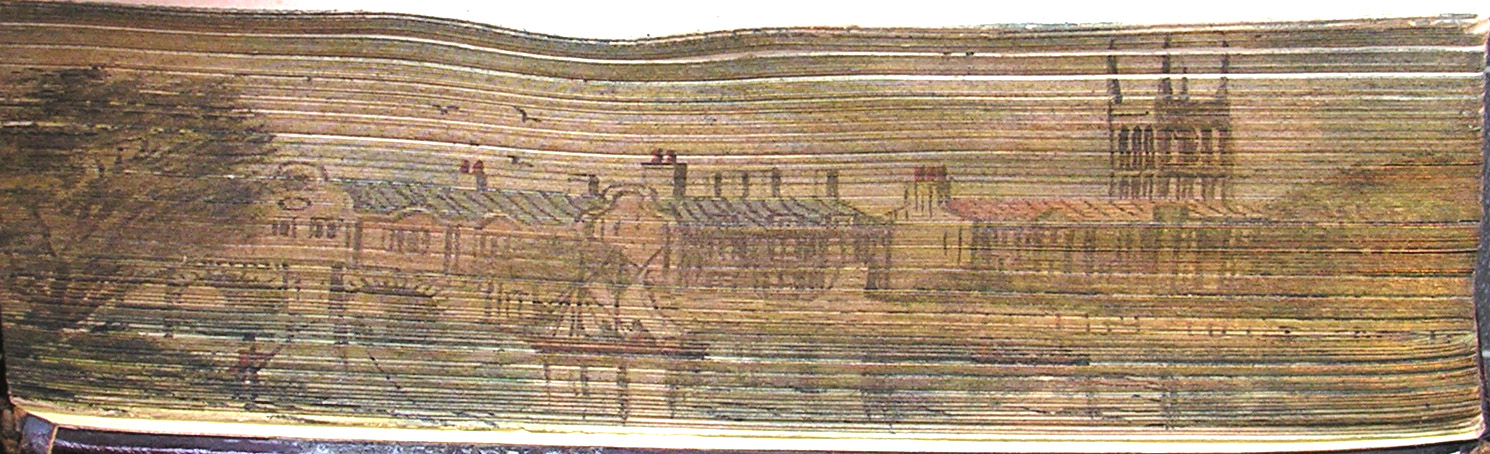

Henry Kirke White, The life and remains of Henry Kirke White, 1843

Another fashion in bookbinding was to paint watercolour scenes along the edges of the pages. These were often completely hidden until the pages were fanned out, which made them a popular place to hide information about ownership of the book (or, occasionally, erotic scenes). This book has a very rare double fore-edge painting – with the pages fanned one way it depicts Nottingham, the other way, St John’s.

Political Trends

Desiderius Erasmus, Institutio principis Christiani, 1529

This book of advice for Renaissance princes uses biblical and classical models to illustrate how a good ruler ought to conduct themselves in contemporary politics. This copy was originally owned by Edward VI, and contains his handwritten annotations in Latin and Greek. After his death, it was given to Elizabeth I, and the binding bears her coat of arms. Remarkably, the closure ribbons have survived from this period.

Torah, 1580

Many wealthy book-owners liked to have all their books bound in a certain style, to make their personal libraries more aesthetically pleasing. William Cecil (c.1520-1598) had this book stamped with his coat of arms. As well as guarding against theft, this was also a way for Cecil to show off his education (and his wealth). Cecil studied at St John’s, and would later go on to become Elizabeth I’s right-hand man.

Book of common prayer, 1669

The interlocking ‘C’s on this binding represent not Chanel, but the earlier fashion trailblazer Charles II. He presented this volume to William Maynard (1623–1699), the controller of his household, and alumnus of St John’s. This visual language of patronage enabled Maynard to prove he was one of the King’s favourites, and also allowed Charles to demonstrate his support of art and his commitment to Protestantism.

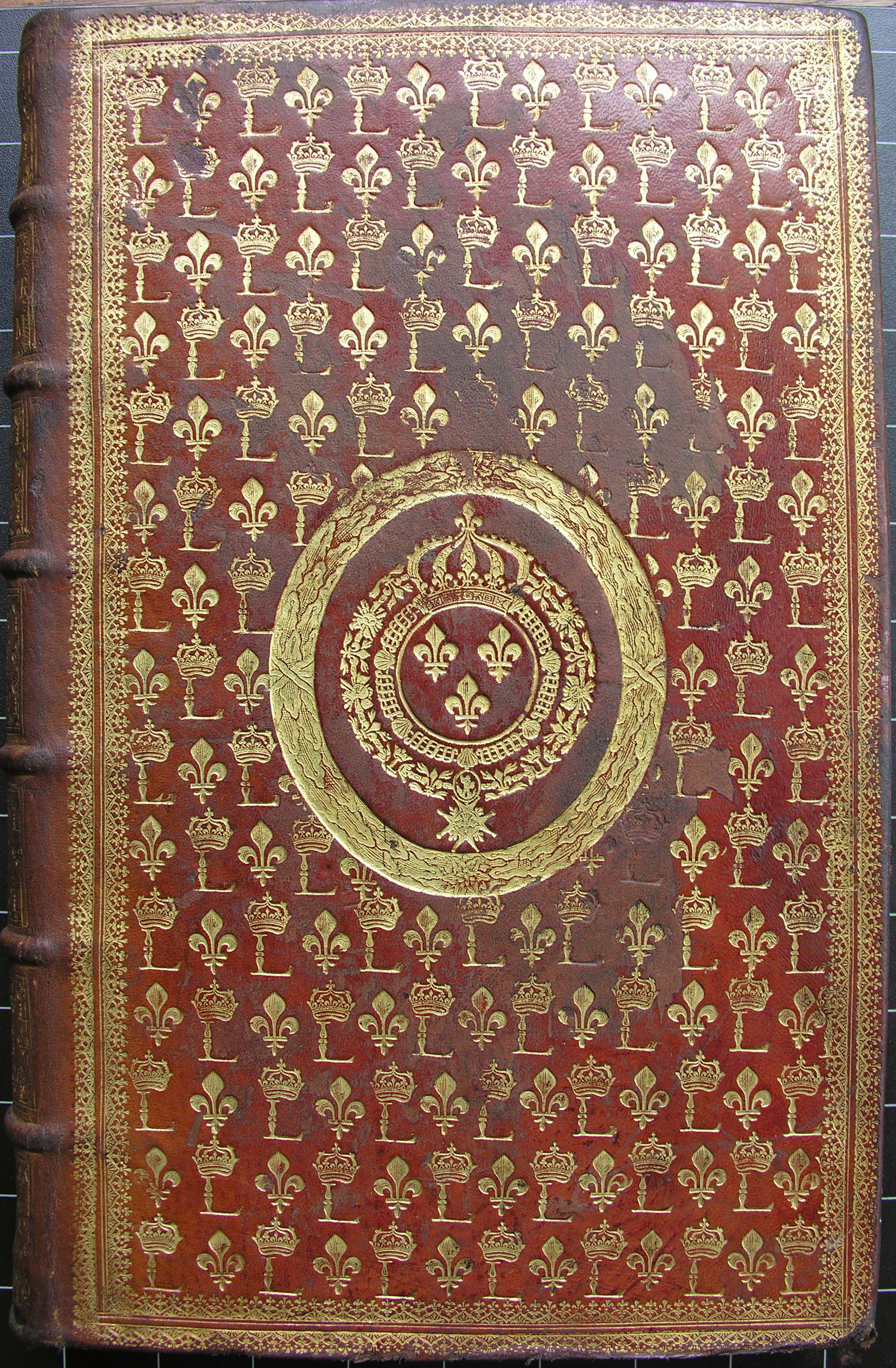

Pierre Lescalopier, Commentary on Cicero’s De natura deorum, 1660

This volume was bound for Louis XIV, and features not only his royal monogram of a crowned ‘L’, but also the French royal badge in the centre, and a repeated fleur-de-lis motif. Louis was not exactly famous for minimalism, and this gilded tome seems to be no exception. Whether he really read his philosophy, or wanted this lavish copy of Cicero’s work more for his own image as a statesman, we may never know.

Making A Fashion Statement

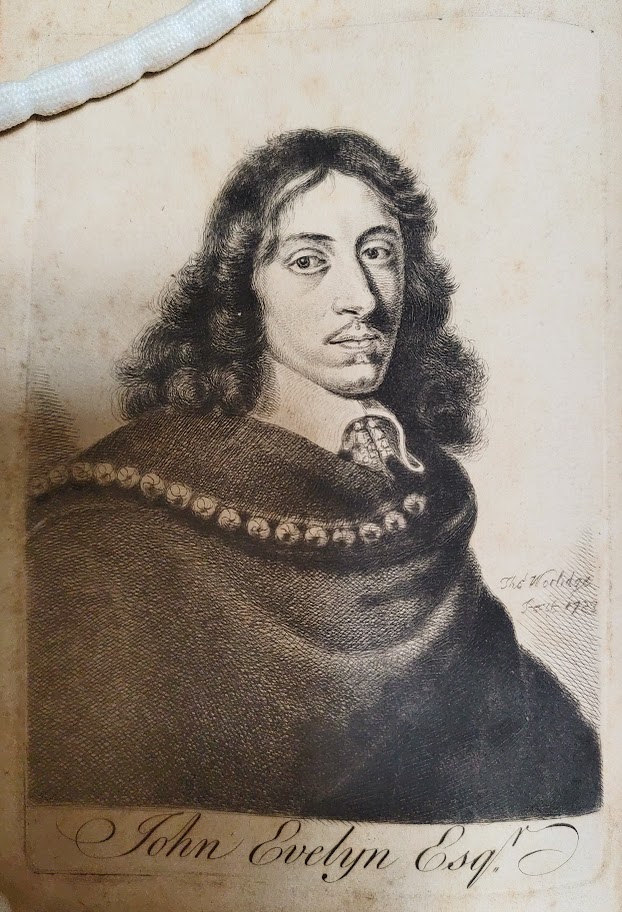

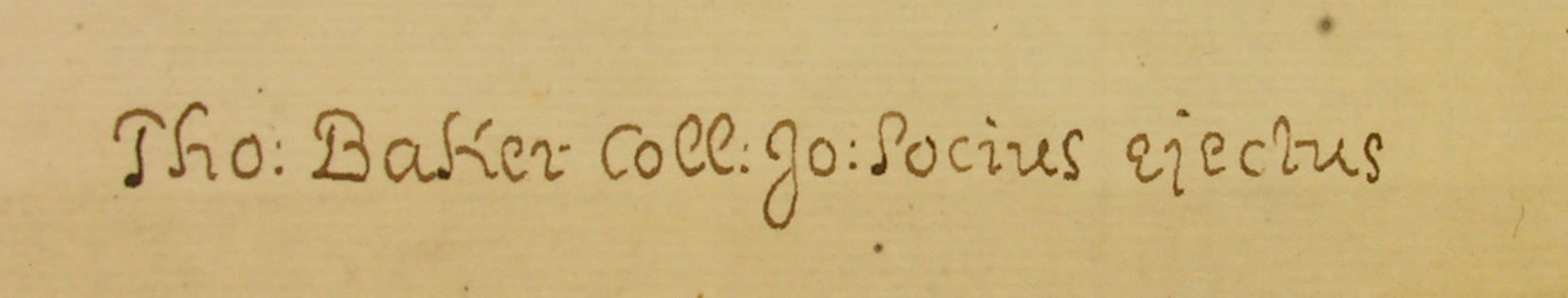

Books are inherently political. But Thomas Baker (1656-1740), a scholar and conservative Anglican clergyman, made sure that anyone who picked up a volume in his library would know exactly what his grievances were.

Baker began studying at St John’s when he was seventeen, and stayed here almost his entire life. He was elected a fellow, and later ordained as a priest. He had made the required oath of allegiance to King James II, a Catholic, but when James was deposed by the supporters of his Anglican daughter Mary II, Baker was asked to swear loyalty to the new regime. He refused. Although he didn’t support James at all, he still felt that his first oath was sacred.

With his Church career in ruins, Baker returned to St John’s, where he wrote Reflections upon Learning. He argued that human knowledge was flawed, and that people should instead humbly trust in divine revelation. Although a huge hit with the public, it didn’t go down well with scientists. Unpopular again, Baker turned to studying the past, and collecting books and manuscripts. It went very well until 1717, when he was again asked to swear his loyalty to the crown and again, he refused.

This time he was removed from his fellowship. He was devastated. Nevertheless, he stayed on as a guest of the college, and left so many books to the library when he died that the bookcases had to be extended to make room. But he wrote his name in all of them as ‘Socius Ejectus’ – ‘the thrown-out fellow’ – so that nobody would ever forget what his college had done to him. A bold and enduring statement from a man who held stubbornly to his moral principles against the tides of fashion.

Crazes, Fakes, & Knock-offs

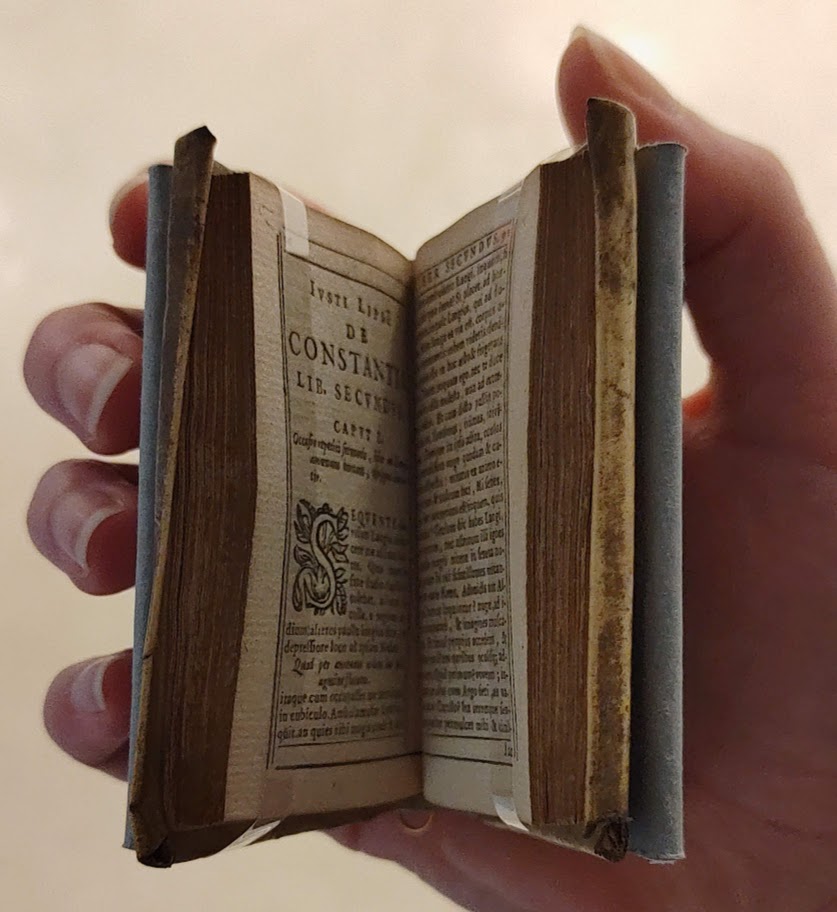

Justus Lipsius, De constantia, 1631 (left)

The vogue for tiny books is credited to the printer Aldus Manutius (c.1449–1515), who developed portable pocket-sized editions of classic works. This was an innovative concept in an age when many books were large, heavy, and chained up in libraries. Philosophical and religious texts were popular, allowing the reader to keep the tenets that were dear to them handy at all times. The fashion has at times got somewhat out of hand: this tiny almanac from the 1800s (right) is barely legible with the naked eye.

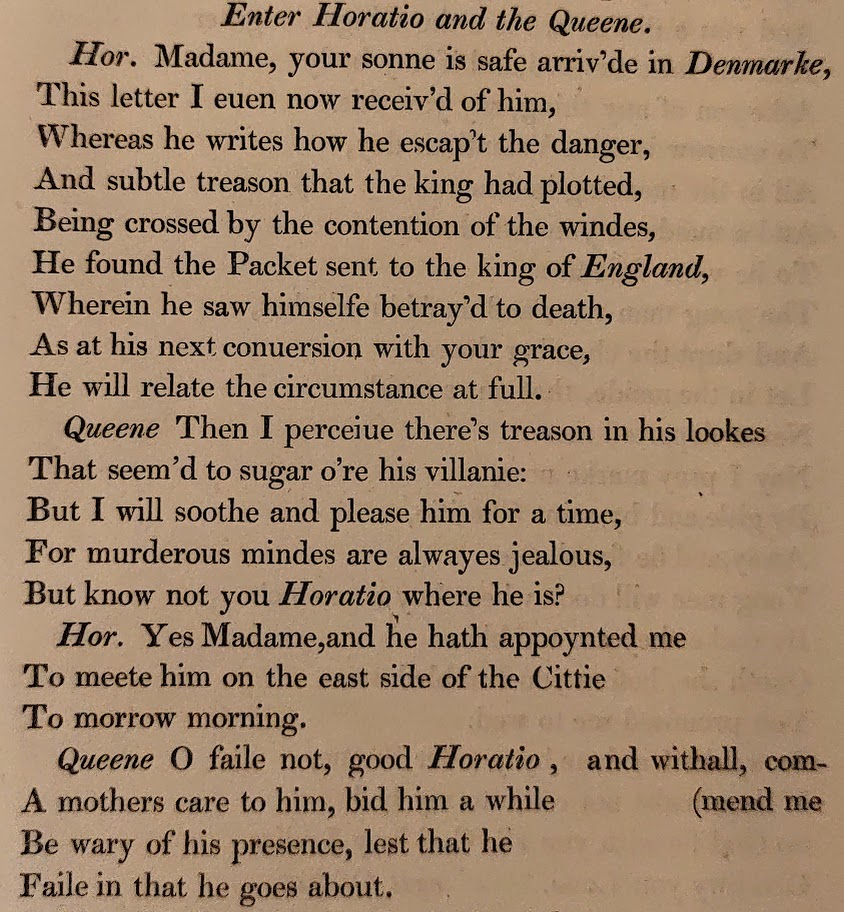

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1603 (1825 reprint)

The craze for play-going in the early modern period was matched by a frenzy of publishing as booksellers tried to profit from the latest hit show. This pacier early edition of Hamlet, the so-called ‘Bad Quarto’, differs significantly from later versions. It may be a pirated text, written up from memory by an actor. Although it has many bizarre lines, it also offers new perspectives on the play: this scene between Horatio and Gertrude, not found in later editions, offers a much more sympathetic portrayal of the queen.

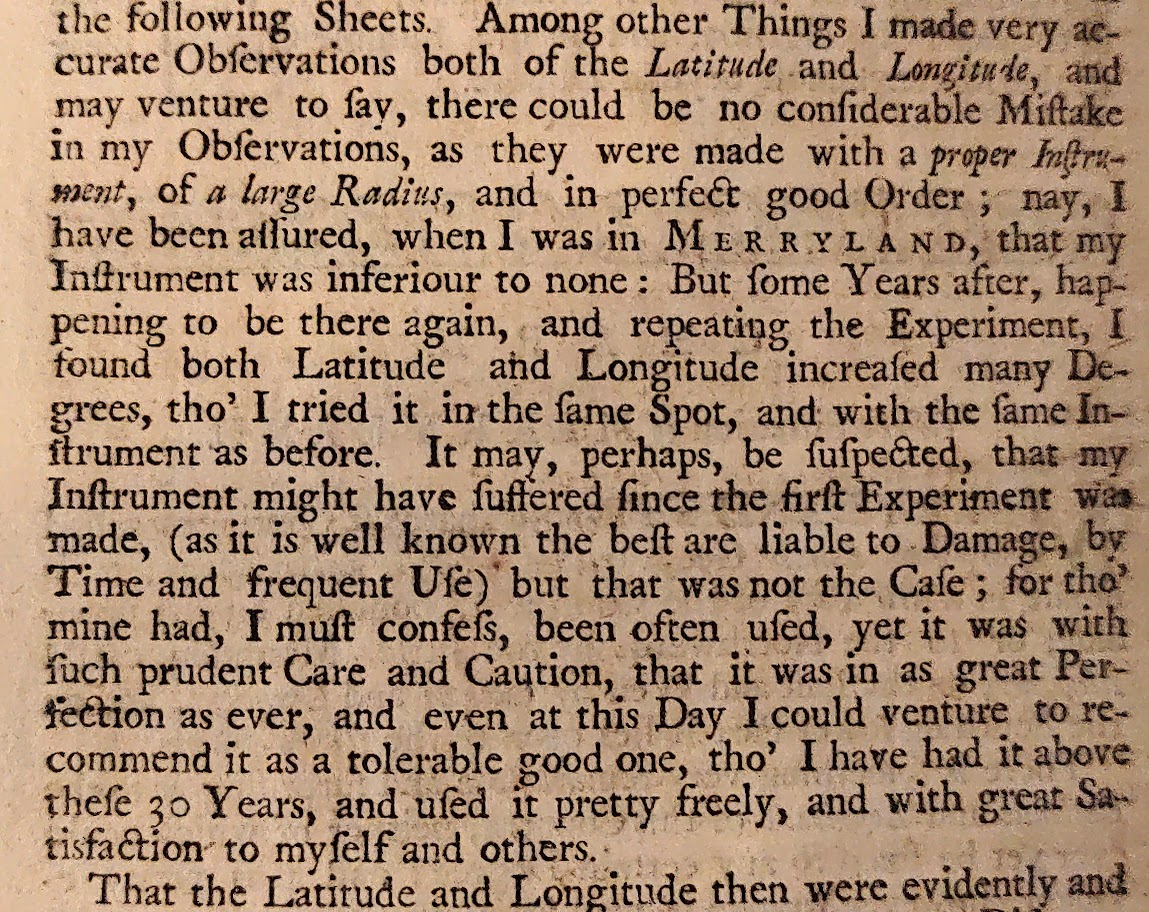

Thomas Stretzer, A new description of Merryland, 1741

Following the fashion for descriptions of daring voyages and distant lands, this work parodies serious geography and applies the format to erotica. The details the book gives of its own publication are mostly fake: it was not, perhaps unsurprisingly, written by ‘Roger Pheuquewell’, nor was it printed in Bath. It was actually printed for Edmund Curll, a notorious London bookseller. Given his reputation for obscene titles, it’s unclear why he would use a ‘false imprint’ to avoid association with this book. Perhaps after being jailed four times, he just wanted to keep his head down.

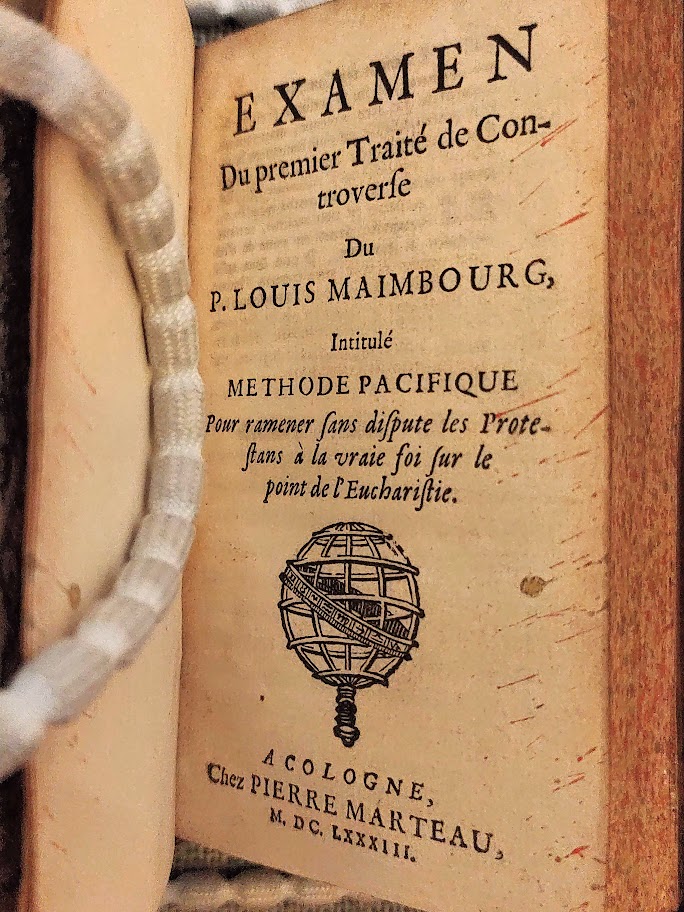

Examen du premier traité de controverse du P. Louis Maimbourg, 1683 (left)

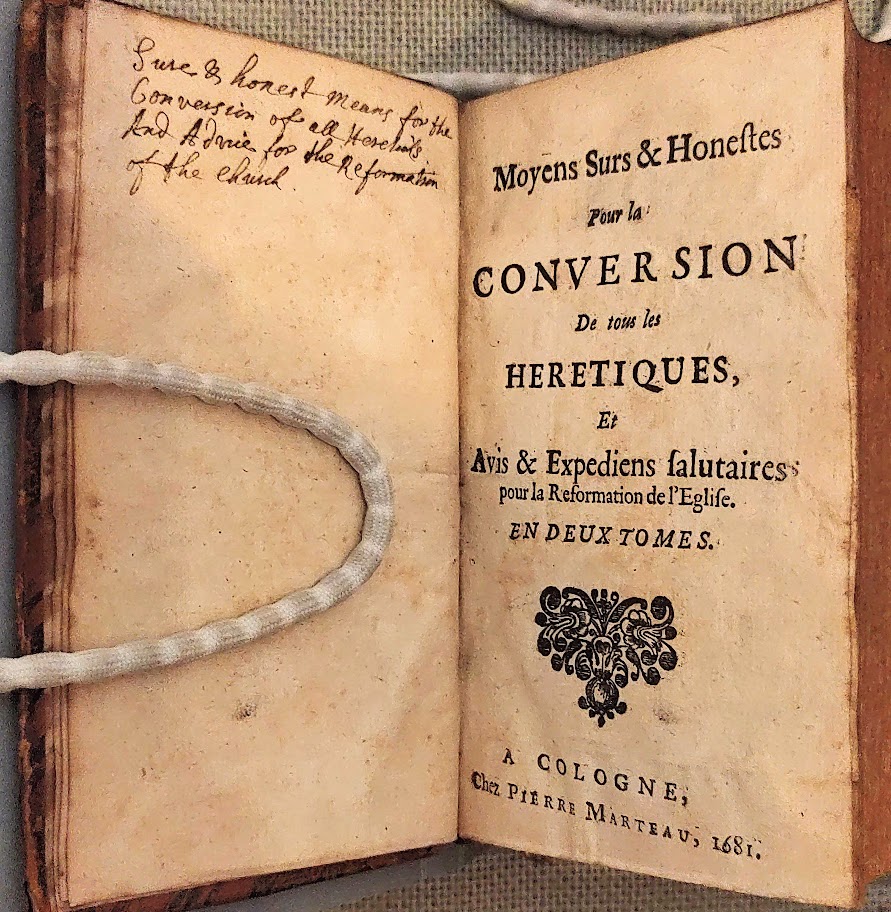

Pierre Jurieu, Moyens surs & honestes pour la conversion de tous les heretiques, 1681 (right)

These books both claim to have been printed by ‘Pierre Marteau’. He never actually existed, and the fake Marteau brand was really a front for other French printers to publish controversial works and avoid censorship. France in the 1680s was a place of deep religious divisions, and these two anti-Catholic works would have been very dangerous to distribute openly.

The Tastemaker

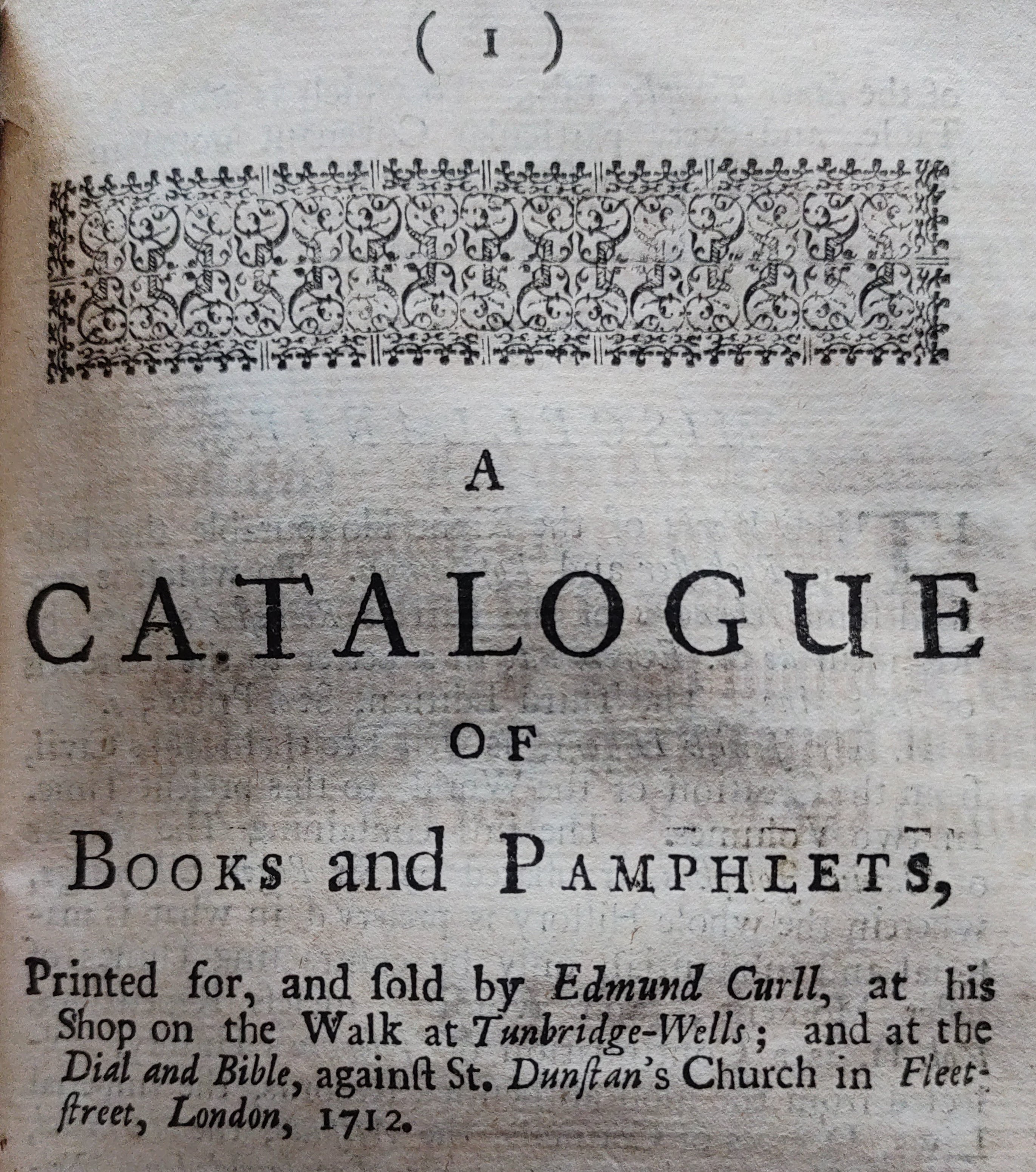

Edmund Curll (c.1675-1747) was a publisher and bookseller, and one of the most notorious figures on the early printing scene. He was a shameless opportunist, expertly manipulating the public debate so that his books were always on trend. In 1712, when Jane Wenham was on trial for witchcraft, Curll teamed up with two other small publishers to write and sell pamphlets arguing both sides of the case.

Curll made sure that he sold something for everyone, and apparently specialised in no particular subject, focusing on whatever would make money. The titles he sold ranged from Caesar’s Commentaries and The Devout Christian’s Companion, to the rather less high-minded The Way of a Man with a Maid, and several dubious medical works claiming to cure sexually transmitted diseases. He became so associated with indecent publications that a new word was coined to describe them: ‘Curlicisms’.

Curll was most famous for his literary feuds. He was unscrupulous about stealing authors’ works and publishing them without permission. He concocted fake new material, and produced unauthorized (and often rude) hack biographies after famous people had died. During Curll’s colourful career he made enemies of Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, John Gay, and many others, and was demonised in the press, pranked with emetics, beaten up by schoolboys, and jailed four times.

But he regarded all publicity as good publicity. Once when forced to write a public apology, he managed to turn even that into an advertisement for his new stock. Although an unsavoury character, Curll was also a canny businessman, who used innovative methods to command the fashions of the book market and shape public taste.

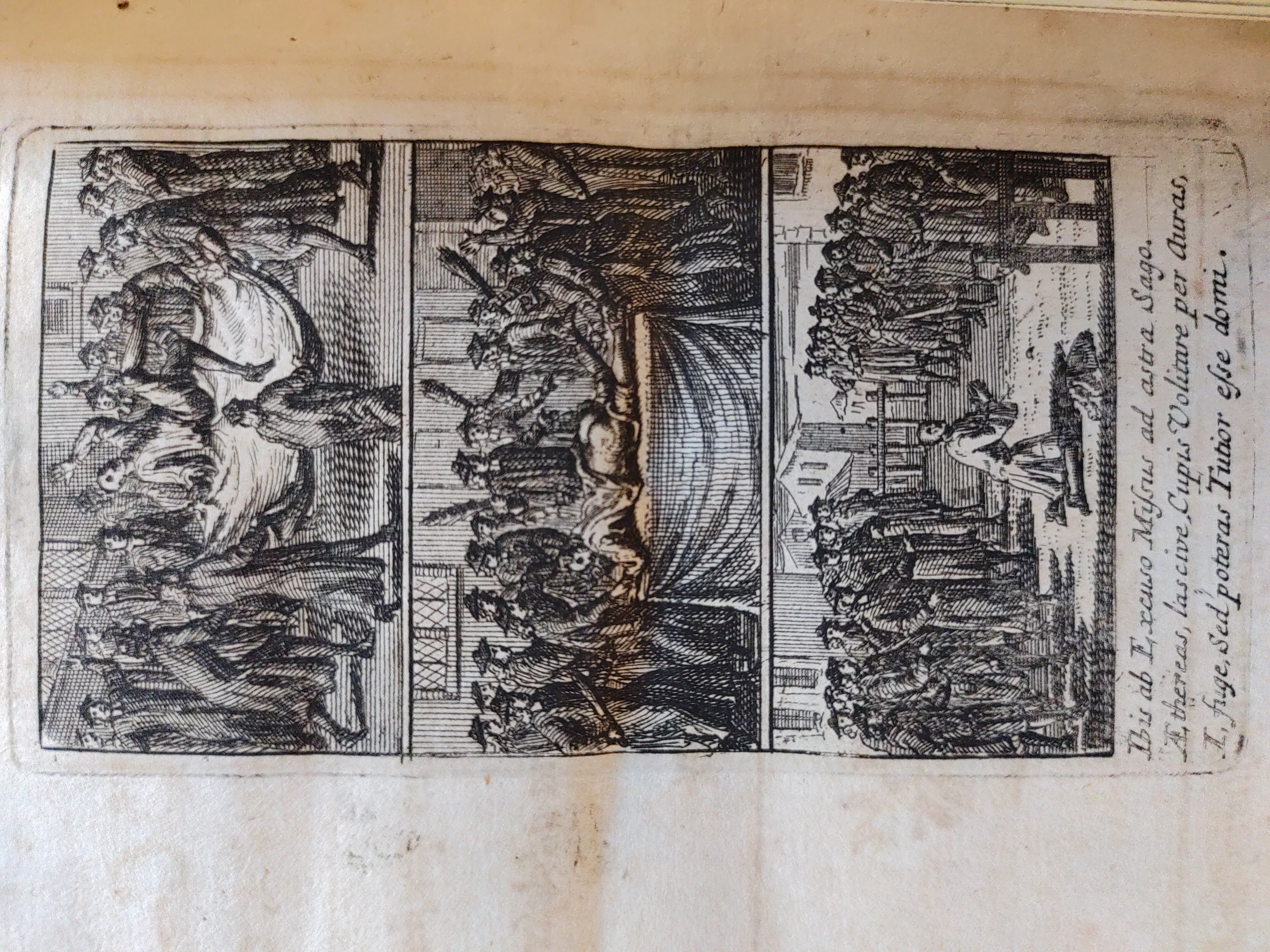

The Printer Who Never Was

Early printed books usually provided their readers with an ‘imprint’ on the title page, giving information about who printed the work and where, as well as sometimes where it was being sold, and for how much. One imprint that began to appear around 1660 was ‘Pierre du Marteau’, who owned a printing business ‘in Cologne’.

The whole thing was a ruse. Publishing under a ‘false imprint’ was a way for printers to circulate controversial texts without associating their own name with them. Avoiding more official channels helped to bypass censorship, possible fines, or other punishments, and allowed ideas to flow freely beyond the control of the government.

‘Peter the Hammer’ was initially a one-off joke, possibly the brainchild of the Elzevir publishing house in Amsterdam. But this was an age before copyright, and the name was quickly adopted by other printers who needed a front for their books. Soon Mr Marteau had a recognisable brand: French-language books of religious controversies and political satire. (And smut.)

Readers began to seek out the imprint as a good source for bold new ideas, and Marteau became so successful that the business was inherited by ‘his widow’ and ‘his son’, as well as various alleged relatives such as ‘J. de Clou’ (The Nail) and ‘Adrienne l’Enclume’ (The Anvil). He wasn’t the only fictional printer of his era. Some books were supposedly printed ‘in the middle of the sea, the house of Henry Herring’ – a long journey to escape the censors!

Today, the Marteau legacy lives on online, where a group of researchers are publishing digital editions of early modern texts.

Written and curated by Caroline Ball, Library Graduate Trainee. With thanks to Dr Adam Crothers, Special Collections Assistant.