Gravy protests, coffee houses and corrupt cooks – digesting the history of student eating at St John’s

“A raucous two-hour Hall meeting in which students complained about the quality of gravy, beer and pastry and sat on the Steward in protest”

Mention food and Oxbridge Colleges, and a vision of luxury springs to mind: a parade of apple-stuffed boars’ heads and sides of roast beef, perhaps, punctuated by the occasional elaborately trussed swan.

Feasting, it’s true, has historically been woven into the fabric of College life: a means of bringing together scholars for the discourse and sociability that encapsulate the collegiate ideal. But, day to day, that same bonding over shared meals is a much lower key affair: more likely today to feature baked potatoes or a vegetarian curry than turbot, oysters and pheasant.

A focus on daily eating is back at St John’s with the imminent opening of the newly renovated Buttery, Bar and Café: a trio of modern, relaxed social spaces where all at the College can eat, drink, study, socialise or just take time out. The updated facilities are entirely contemporary, but a glance at the history books confirms the tradition of informal meals – and the drinks that accompany them – stretches firmly back into the College’s past.

Records reveal a colourful and sometimes turbulent picture, featuring grievances about overcharging, fines for those spending too long in nearby coffee houses, repeated kitchen refurbishments, and – in 1884 – a raucous two-hour Hall meeting in which students complained about the quality of gravy, beer and pastry and sat on the Steward in protest.

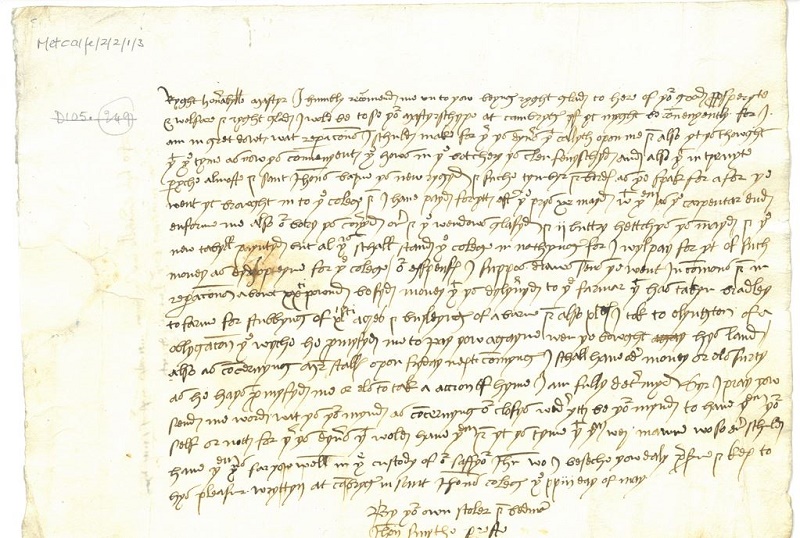

The eating habits of students are difficult to trace in the earliest centuries of the College’s existence, though a Hall, together with a Chapel, Library and residential accommodation, was among the buildings constructed around St John’s’ First Court following its foundation in 1511. By around 1519, a letter to the Master of St John’s, Dr Metcalfe, from a College official signing himself “John Smythe, your own scolar and bedman”, included details of a Buttery among a list of building works. “The botry [buttery] is couryd ouer [covered over] and the windows glasyd [glazed] and ij buttry hettchys ys mayd [each buttery hatch is made] and the new tabyll paynted.” Not only that, the improvements came cost-free, Mr Smythe boasted, as he had raised the funds himself: “…but al these shall stand the Colege in nothing for I wyl pay for yt of such money as dyd I opteyne [obtain] for the Colege.”

“As St John’s expanded, feast menus followed the seasons: fishponds on the site of present-day New Court provided freshwater fish as a winter supplement, while geese were on the menu for large dinners”

By the following century, as St John’s expanded, records show feast menus followed the seasons: fishponds on the site of present-day New Court provided freshwater fish as a winter supplement, while geese were on the menu for large dinners and in 1637 payment was made for two breeding swans and nine young ones “to stocke the Colledge swan mark”.

Fast forward again, and the 18th century arrival of coffee houses in Cambridge was luring students out of College for food, drink and – crucially – newspapers, providing an opportunity for political discussion as well as refreshment. The Johnian coffee house operated in All Saints Yard, opposite the front of the College, from the 1740s, and seems to have been superseded by Clapham’s about 20 years later. Another was located on the site of the present Corfield Court, where archaeologists excavating in 2007 found teapots, coffee cans, bottles and jars, together with a food waste pit revealing strawberries, figs and grapes were on the menu alongside meat and fish.

The popularity of the forebears of Starbucks and Costa among students – particularly during study hours - eventually prompted a clampdown at St John’s. In 1750, Senate accepted a new code of regulations: “Every person in statu pupillary who shall be found at any coffee house, tennis court, cricket ground, or other place of public diversion and entertainment, betwixt the hours of nine and twelve in the morning, shall forfeit … ten shillings.” Taverns and coffee houses risked a fine and ultimately loss of their licence if they served students alcohol after 11pm, though students who could pay fines were able to get away with the infringements.

By the nineteenth century, the voices of students are heard more clearly in St John’s’ records, including, in the 1860s, complaints of overcharging for food as kitchen staff made a profit from indulgent undergraduate eating habits. There was no fixed tariff of charges, and the College cook dodged all inquiries into costs, supplying students in their rooms with large, expensive breakfasts, sometimes of poor quality. The flaws in this early form of Deliveroo outraged his young customers. “When you want a breakfast for your friends,” protested one, “more fish is served up than you want… To prevent this extravagance in executing orders, men have tried … to order fish (for example) for four and plates for eight but this is defeated by the cook…”

College authorities responded by abolishing all ‘sizings’ (Buttery purchases) other than those in beer. Five years later, a new system was introduced whereby students could order portions or meals at a fixed price according to a set tariff, and all kitchen affairs were placed under the control of a steward rather than the cook. A standing body was created to regulate charges in Hall and for students’ private purchases.

Problems continued, however. An experiment with lower-cost but rather luxurious food sourced from London to avoid local cartels was withdrawn in 1884, and undergraduates demanded a two-hour meeting after Hall to discuss complaints. One student wrote: “It was awful fun, Fellows got up and complained about all sorts of little things (gravy, pastry, beer, vegetables etc etc) and sat on the Steward, who is a Don. I didn’t go home till 10.30…”

“'Tonight’s dinner was inexcusable,” wrote one disgruntled undergraduate, claiming the mashed potatoes were “held together with glue” while the meat was actually leather’”

The turn of the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth saw a series of moves to enlarge and modernise the College kitchens and Buttery to suit changing needs. In 1893, during extensive alterations, Chamber F2 – the room occupied by William Wordsworth from 1787-91 – was incorporated into the kitchens to give more light and ventilation, though its structure was restored in another remodelling phase in 1951. The latter redesign also combined the kitchen shop and scholars’ Buttery into one facility with a counter dispensing beer, bread and milk to students, ending their need to trek through ‘Stankard’ passage where they got in the way of kitchen traffic to and from Hall. By this time, bread was sourced from the town bakery, as the College’s own bakehouse had been closed down under a Ministry of Food edict early in the Second World War.

A 1950s ‘Suggestions book’, in which junior members could record proposals and – more often – complaints for the College Kitchen Committee, sheds revealing light on the highs and lows of student eating at St John’s, and on the elevated expectations of some young diners. “Tonight’s dinner was inexcusable,” wrote one disgruntled undergraduate, claiming the mashed potatoes were “held together with glue” while the meat was actually leather. “Is it too much to ask that the bread supplied in Hall is fresh?” lamented another, while a third grumpily challenged the ratio of mint to vinegar in the mint sauce.

Students offered a range of more constructive suggestions for developing the Buttery, though the pencilled responses added by committee representatives on the book’s opposite page were far from universally positive. A plea that bottled Guinness might be stocked was agreed to, but a request for a dartboard in the Buttery for lunchtime drinks was swiftly dismissed: “I think there isn’t room or occasion for this”. Likewise, a proposal that the Buttery “stock Scotch whiskey for die-hard Scotchmen” fell on deaf ears: “There is a Council rule that no spirits should be available to undergraduates in the Buttery. The Scotsmen must therefore die hard elsewhere”.

Calls for a wider range of cigarettes (“Players Senior Service, or the cheaper brands”), ham sandwiches and “a selection of good cheeses, including Camembert and Brie” were briskly rejected, together with a plea for fresh fruit: “I’m sorry, but past experience has shown that this is doomed to wasteful failure”. Some concessions were made, however: a request for non-alcoholic drinks prompted the introduction of lemonade and ginger beer, plus still drinks at fourpence a glass, and a proposal that the Buttery stock “a limited variety of confectionary” led to a promise of fruit gums.

Just a few years later, in 1960, the Buttery was modified again, almost doubling its floor area, followed by another extension in 1962. Finally, reflecting a shift to less formal eating habits across all colleges, the whole ground floor west of O staircase and as far as K staircase in Second Court was radically reconfigured by 1972, creating a larger Scholars’ Buttery and an informal self-service dining space for undergraduates.

The reasons behind the redesign were remarkably familiar: the need in tough economic times to provide better value options for students, demand for self-service and greater choice, and pressure for equal access to the facilities for senior and junior College members as rigid hierarchies loosened. There was another welcome rule change, too: women could now be admitted as guests in the new dining area, providing an opportunity for social mixing in the still all-male College.

The latest iteration of the College’s eating and social spaces continues the long tradition of moving with the times in response to the changing needs and habits of students. Self-service food, with an emphasis on quality, choice, local and sustainable sourcing, and affordability is now standard. Newer is the focus on combining work with refreshment: laptop and phone charging points are available at tables, and the facilities are envisaged not only as a place to eat and drink but as additional study spaces to be used flexibly throughout the day.

The decor, too, is new: the colours are modern, muted and calm, the furniture simple and contemporary beneath an architect-designed oak-framed roof, and one side of the Buttery boasts a plant-covered ‘green wall’, watered by rainwater.

Underneath that new roof, however, the fundamentals are the same as they were when John Smythe penned his letter in 1519: a place for students to sit, eat, drink and spend time together.

*Many thanks to Dr Lynsey Darby, College Archivist, for her research assistance for this article.

Published 27/01/2023