Exhibition tells the story of children's literature from medieval times to 1960’s

From historic schoolbooks and traditional fables to classic adventure stories, and from poems and songs to riddles and picture books, an exhibition that showcases the highs and lows of children’s book publishing over seven centuries, opens for the festive season at St John’s College Library, University of Cambridge.

An exhibition open for the festive season at St John's College Library, Cambridge, celebrates children’s books, from medieval programmes of Latin and religious instruction to the colourful Ladybird books that taught a British post-war generation to read, and explores what they can tell us about changing attitudes to education and literacy.

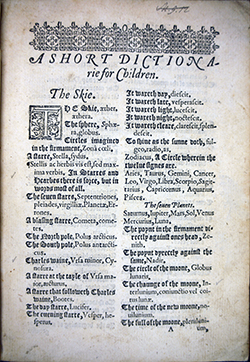

In the middle ages literature aimed at the young reflected the generally accepted view that children were born sinful and in need of redemption. Children’s books were designed to be instructive rather than entertaining and provided moral and religious guidance as well as tuition in subjects like Latin and Maths.

One of the earliest items in the exhibition of items from the Library’s special collections is a programme of Latin instruction by Roger Ascham, Fellow of St John's College and Royal Tutor to Princess Elizabeth, later Queen Elizabeth I. The Scholemaster, published in 1570 after Ascham’s death, was originally written to show his sons Giles and Dudley “the right way to good learning” and took a practical approach to education, focusing on the specific knowledge and skills a gentleman needed to fulfil the offices of government and conduct himself properly at court.

Written a little over a century later, another highlight of the exhibition exudes a strikingly modern philosophy: Some Thoughts Concerning Education, a treatise by the philosopher John Locke, first published in 1693.

Locke's treatise, which remained the most important work on education in England for over a century, was radically different as it was based on the belief that the human mind is a blank slate on which potentially anything can be written. Locke argued that while instilling a sense of right and wrong was important, every child should be treated as a rational entity, to be reasoned with instead of commanded and punished.

Addressed to parents rather than teachers, the treatise formulated the idea of making education entertaining for children, stating that priority should be given to teaching them how to learn and ensuring that their education is interesting, relevant and enjoyable. For education to succeed, Locke asserted, children must want to be educated.

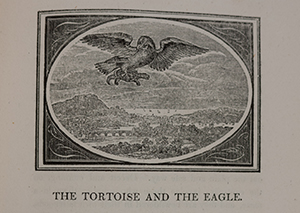

Locke’s principles are also showcased through a copy of his edition of Aesop’s Fables, a collection of animal stories with morals. Significantly, the work is illustrated, as Locke perceived that “if his Aesop has pictures in it, it will entertain him much better”.

Locke's practical attitude and enlightened philosophy seems far more familiar to the modern reader than the children's literature featured in the display from the Victorian era, when the moral emphasis in children's books resurged.

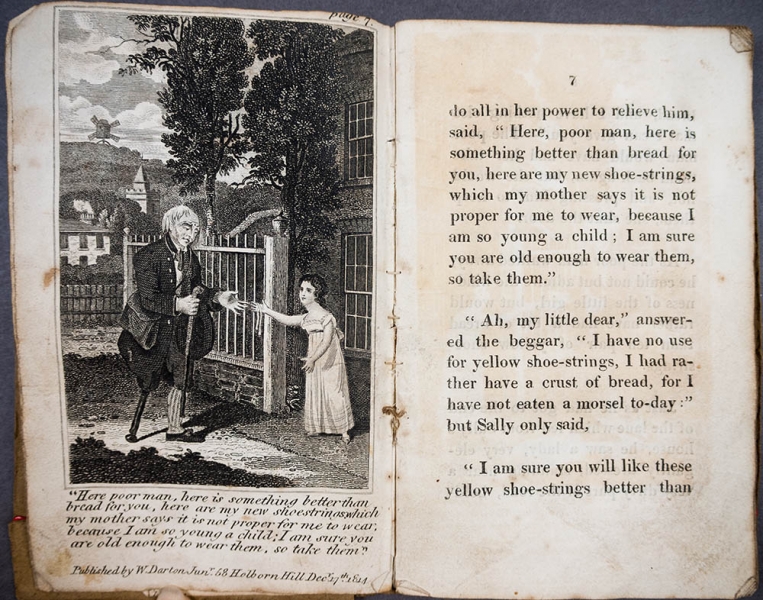

The Yellow Shoe-strings; or, the Good Effects of Obedience to Parents (1814), offers a domestic example of the kinds of tales young minds were exposed to at a time when moral and religious learning was again considered to be the only important purpose of books for children. A contemporary advertisement, also on display, for a book titled, The Little Tradesman; or, a Peep into English Industry (1824), dismisses the “tales of useless and dangerous fiction, of fairies, giants and monsters” previously written for children, preferring to champion the exemplars of “intellectual improvement” characteristic of the 19th Century.

Kathryn McKee, Special Collections Librarian at St John’s and curator of the exhibition, remarked: “In the aftermath of the of the Enlightenment, educational theory and practice seemed to take a backwards turn, reverting to the strong emphasis on religious and moral instruction that had dominated during the middle ages,”.

“While the output of children’s literature increased significantly during the 19th century, many of the works aimed at the juvenile market were didactic, moral tales, designed to promote good behaviour and Christian values.” Kathryn explained.

It is possible that the shift back to books of explicit moral instruction was partly aided by technological developments. Vast improvements in printing and illustration meant that moralistic literature could more easily be made to appear appealing to children, and a variety of chapbooks featured in the exhibition illustrate this.

Chapbooks are small-format books, manufactured from a single sheet of paper and visitors to the exhibition can see how to make their own. Originally developed to aid the circulation of political pamphlets and almanacs, they were the ideal size and format for appropriation by the children’s market.

The colourful Ladybird books still published today and which promoted literacy among a whole generation of post-war readers in Britain, are a modern take on the chapbook format. Perhaps surprisingly for a Cambridge College Library, St John’s holds a few volumes from the Ladybird series, such as the science fiction adventures titles authored by the astrophysicist and late Fellow of St John’s, Fred Hoyle.

Kathryn McKee isn’t totally convinced that much has changed since the great age of the fairy tale: “Now we would say there’s more emphasis on “fun” in children’s books – the morals aren’t so blatant – but most stories written for children still follow the traditional formula of “good” characters triumphing and “bad” characters getting their comeuppance by the end.”

Some Earlier Age: Children’s Books in the College Library runs until 29 January in the Library Exhibition Area, and is open to the public Monday to Friday, 9am-5pm. Please note that the exhibition will be closed from Christmas Eve to New Year's Day inclusive.