Ancient litter reveals history of ordinary people who lived during first Mediterranean ‘superpower’

“One of the strengths of archaeology is its potential to reveal the lives not just of the people who wrote history but also the silent majority ‘beyond history’”

The lives of farmers and shepherds who toiled on the land in Italy up to 8,000 years ago have been pieced together for the first time in a new book.

The Etruscans ruled Etruria – now the western side of Italy between Rome and Florence – between the eighth and fourth centuries BC when their civilisation was absorbed by the Roman Empire, and their people were the first ‘superpower’ of the Mediterranean along with the ancient Greeks.

Archaeologists and historians have learned about the lives of wealthy Etruscans from excavated tombs, but 95 per cent of Etruscans were countryside-dwellers, and their lives had remained a mystery – until now.

Professor Graeme Barker, Cambridge University Disney Professor of Archaeology Emeritus and Fellow of St John’s College, who co-led fieldwork in the area, said: “In Roman and medieval times, too, we mostly know about ordinary people in the Italian countryside from what the urban elites write about them. One of the strengths of archaeology is its potential to reveal the lives not just of the people who wrote history but also the silent majority ‘beyond history’ or ‘denied history’ – because we all leave behind ‘stuff’ for archaeologists to find.”

The unrecorded history of generations of Etruscan, Roman and medieval farmers and shepherds who once lived within a 10k radius of Tuscania, a small walled medieval town near Rome, have been revealed by the landscape archaeology project that collected 100,000 artefacts from ploughsoil in the late 1980s.

The fieldwork was carried out in a bid to better understand the processes that shaped the development of the modern Mediterranean landscape as a physical and cultural construct.

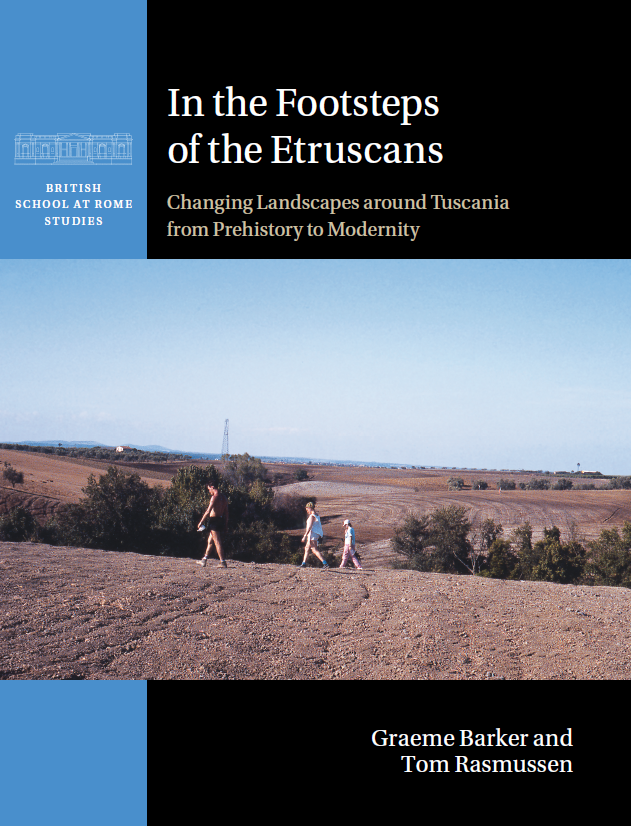

The project had particular focus on the changing nature of the relationship between town and countryside, using Tuscania as an example. During the project, teams of archaeologists walked more than 350 square kilometres of fields to pick up ancient rubbish churned up by the deep ploughs of modern Italian farmers.

Professor Barker undertook the fieldwork when he was Director of the British School at Rome, with Etruscan archaeologist Dr Tom Rasmussen, of the University of Manchester. Professor Barker said: “After bringing together more than 30 years of archaeological evidence by more than a dozen specialists, the result is an unrivalled 8,000-year ‘archaeological history’ of a typical Italian landscape.”

The findings are reported in their new book, In the Footsteps of the Etruscans: Changing Landscapes around Tuscania from Prehistory to Modernity.

“We found classical Greek pottery so it looks like these farmers, and not just the elites, were part of a Mediterranean system of gift exchange and trade”

The researchers have mapped where people lived around Tuscania before the town even existed and identified changing trends to the present day. “We had tiny bits of evidence for when Stone Age people lived by hunting and gathering in Italy. Then we started locating small farmsteads that belonged to the first Neolithic farmers and the Bronze Age hierarchical societies that succeeded them. By the Iron Age, in the early first millennium BC, we started seeing people coming together for protection in fortified hilltops, and Tuscania was one of them. This is really how cities began in Italy although the majority of ordinary people lived in the countryside.”

What was most surprising was how much material they discovered documenting the rural population around the Etruscan, Roman and medieval town.

“A small Etruscan farm we excavated had facilities for making wine and olive oil, and processing wool into textiles. We found classical Greek pottery so it looks like these farmers, and not just the elites who were buried in the wonderful painted tombs of Tarquinia – the city to which Tuscania was probably tied to – were part of a Mediterranean system of gift exchange and trade.”

The Roman farms ranged from small peasant farms, little more than shacks, to villas owned by the aristocracy, identified by the existence of roof tiles, well-made pots and exotic items from throughout the Roman Empire. “These large villas were typical of the slave economy at the heart of the empire,” said Professor Barker.

The rural population would have helped to feed the city of Rome and they were also part of what we would call globalisation today. “It’s interesting that things happening on the fringes of the Roman Empire could affect a small farm near Rome. What we eventually start to see in the final centuries of the Roman Empire is a depopulation of the countryside and reconfiguration of the landscape as more people moved to the safety of fortified hilltop towns. It’s a trend we see across the Mediterranean.”

The field data record reveals a landscape that has been transformed in recent decades, which means the ‘field-walking’ archaeology techniques used would be near impossible to repeat around Tuscania today.

Traditional farming methods, such as polyculture – the system probably first established in the Etruscan period in which cereals, vines and olives are grown inter-mixed – have been replaced by mono-crop industrialised farming. Combined with deep ploughing, this type of farming is making the landscape even more vulnerable to erosion, as is being seen all round the Mediterranean basin.

The landscape is also being impacted by climate change and tourism, with holiday homes now dotting the countryside where ordinary Etruscans once trod.

* In the Footsteps of the Etruscans: Changing Landscapes around Tuscania from Prehistory to Modernity by Graeme Barker and Tom Rasmussen (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Top image shows the view from a major Roman site towards the medieval habitation and burial area represented by the medieval sites on the slopes below. Tuscania is visible in the distance. Credit: Graeme Barker.

Published 21/11/2023