All in the bones

“It revived many old memories, ghosts from a distant past”

A student’s family ties to the discovery of Neanderthal remains more than half a century ago have added another layer to the research of two St John’s academics. Karen Clare began digging to find out more.

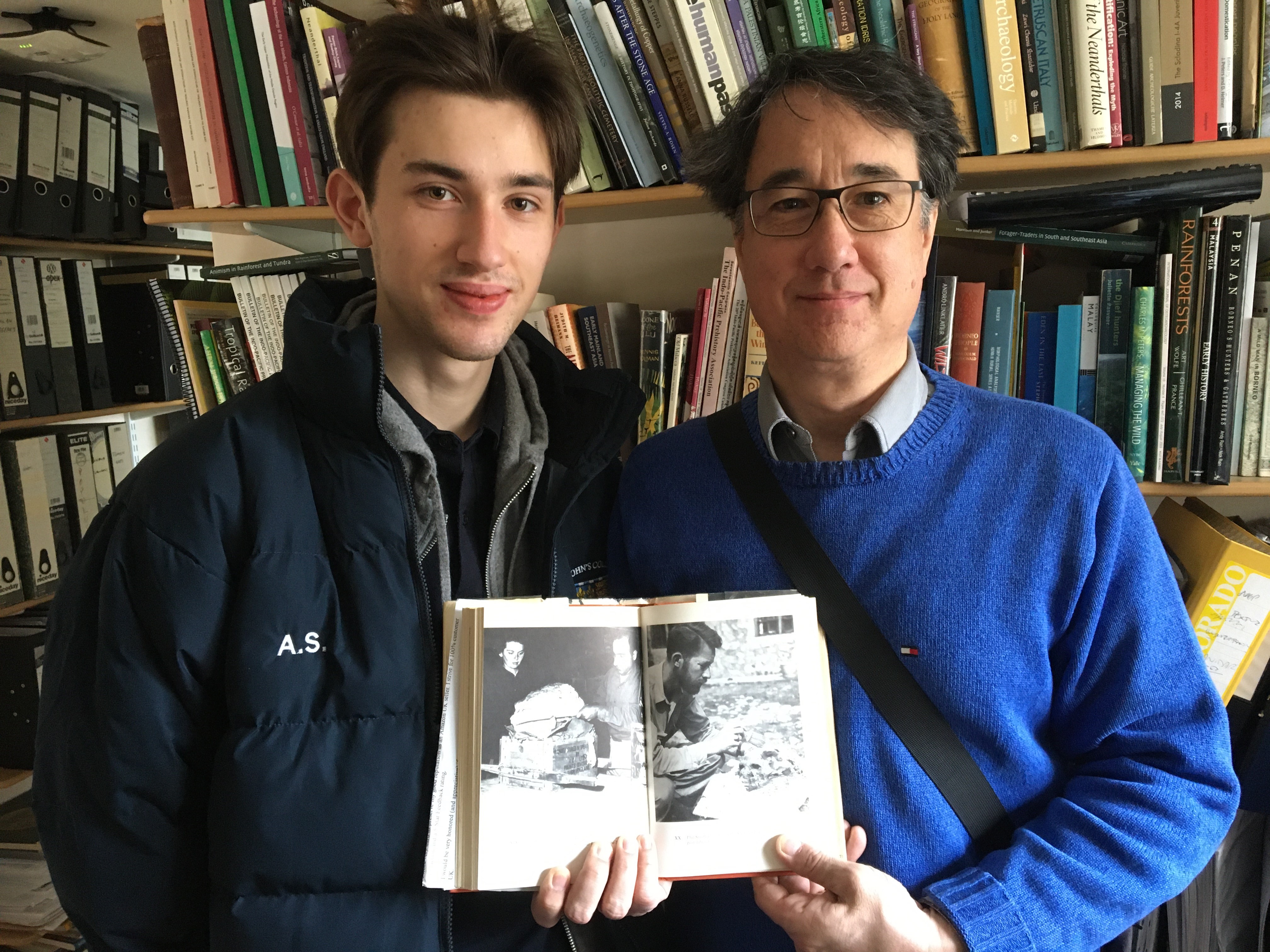

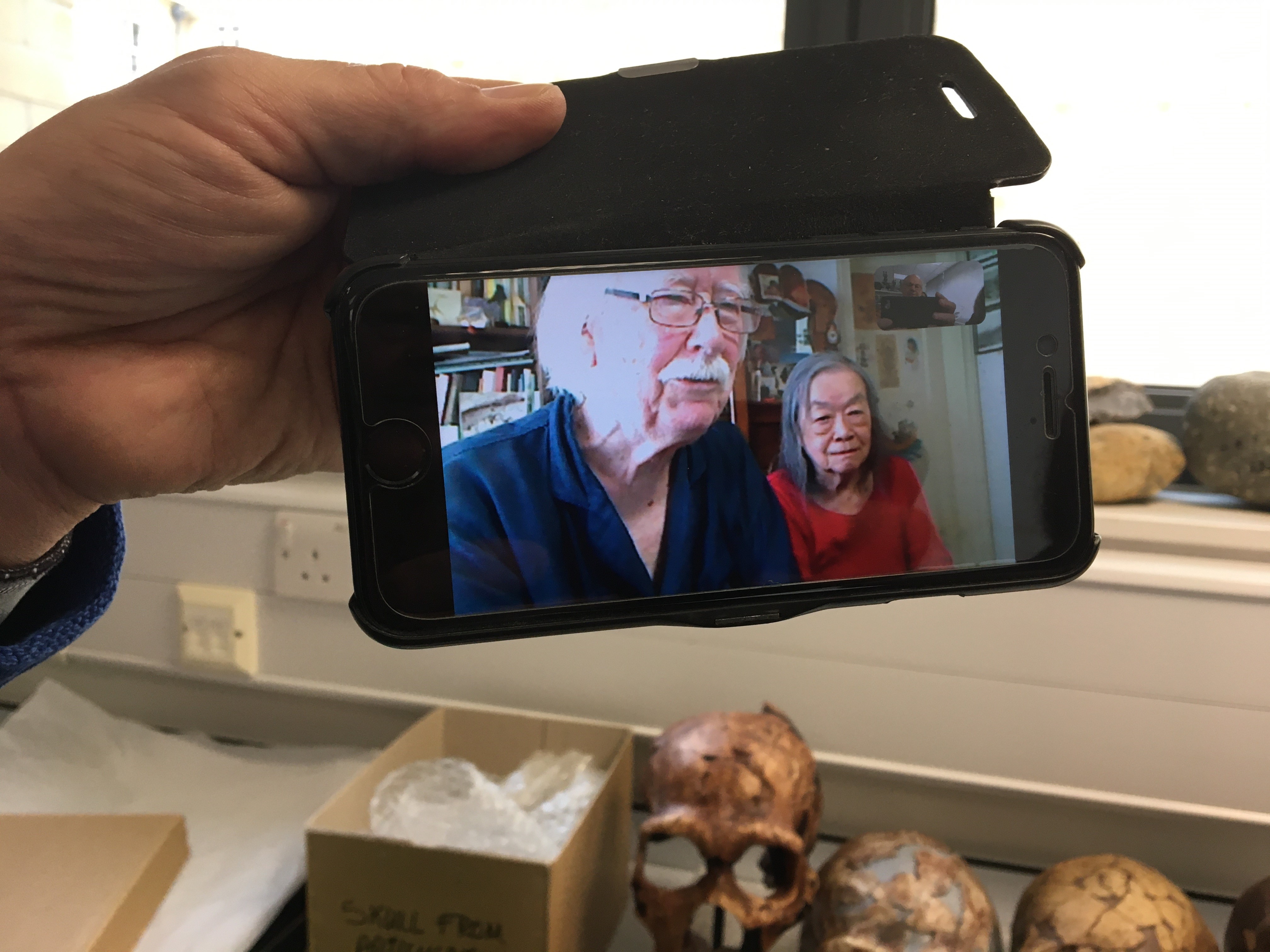

When St John’s undergraduate Andrew Smith spoke to his grandfather, Philip, during a visit to Cambridge Department of Archaeology in April, the video call brought together three archaeologists who worked on the same world-famous excavation six decades apart.

In 1957, Philip Smith was involved in the excavation of the Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, famous for the discovery by Professor Ralph Solecki of several Neanderthal burials during his 1951-1960 excavations – including an adult badly injured as a young man who must have been cared for by his community, and another one possibly interred with flowers. In 2017, St John’s Fellow Professor Graeme Barker’s team uncovered an articulated Neanderthal skeleton at the cave, which is probably the most important Neanderthal find for a generation.

The evidence for the flower burial has been questioned, but the Solecki discoveries have played a fundamental role in demonstrating that Neanderthals, our closest evolutionary cousins, were far closer to us in their behaviour than originally assumed. Professor Solecki was unable to complete his excavations because of political turbulence and, in 2011, Professor Graeme Barker, Disney Professor of Archaeology Emeritus and Senior Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, was invited by the Regional Government of Iraqi Kurdistan to re-excavate the cave. He has been directing excavations there since 2015.

When Professor Barker learned that Shanidar veteran, Phillip, was still alive at the age of 94 and that his grandson was a student at St John’s, he invited Andrew and his parents on a tour of the lab with Cambridge colleague Dr Emma Pomeroy, Assistant Professor in the Evolution of Health, Diet and Disease at the Department of Archaeology, to view the restoration work on the new skeleton they have found, known as Shanidar Z.

Philip, who lives in Montreal, Canada, joined the tour in the Henry Wellcome Building via video call and regaled the group with tales of his time at Shanidar under the direction of Professor Solecki. Philip was an archaeology postgraduate based at Harvard, where he and wife Fumiko Ikawa-Smith met, when he was instrumental in the discovery of the Neanderthal skeleton known as ‘Shanidar 1’, the badly injured male, and later, ‘Shanidar 2’.

On their lab tour, the Smith family were able to see the restoration being undertaken by Dr Lucia López-Polin Dolhaberriague, a leading conservator of human fossil bones based at IPHES, the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana I Evolucio Social in Tarragona, who is working with Dr Pomeroy on the conservation and analysis of Shanidar Z. Like the ‘flower burial’, Shanidar Z is approximately 75,000 years old.

Philip said: “I was astonished and overwhelmed to join in the video call from the lab and see Shanidar Z at last. I only wish I could have been there in the flesh. It revived many old memories, ghosts from a distant past.”

Grandson Andrew is in the second year of his Natural Sciences degree, focusing on Physics and Maths, and has a lifelong interest in geology and archaeology. He said: “Seeing the new Shanidar Z skull in the process of reconstruction by Lucia and Emma was especially fascinating – it was like a very complex puzzle.”

“It was a real privilege to show the Smith family the work we are doing with the new Neanderthal remains from Shanidar Cave”

In the case of Shanidar 1, Solecki believed his kin-group must have been sufficiently compassionate, altruistic and close-knit to support him until death, before burying him respectfully in the cave. Philip said: “From this interpretation one could argue for the essential humanity of Neanderthals in general, thereby modifying the traditional caricature of them as clumsy, brutal and even subhuman.

“Of course the discovery in 1960 of the Shanidar 4 burial with traces of flower pollen was like icing on the cake for this interpretation. We are all looking forward to the results of the new excavations in the cave, to confirm or reject the flower burial hypothesis.”

Professor Barker led the team from the University of Cambridge, Liverpool John Moores University, Birkbeck University of London, Canterbury Archaeological Trust, University of Oxford and Canterbury Christ Church University that unearthed the crushed skull and torso of Shanidar Z in 2017.

He said: “It was extraordinary to see Philip and hear his stories, and to have him there on screen, looking at the fruits of our labour, our modern work, in light of his own work. It feels as if it has come full circle.”

Although Philip and Fumiko, who is an archaeologist in East Asian studies, are both retired from university teaching, they had heard of the renewed excavations at Shanidar Cave and followed the progress with interest. “The wheel only turned full circle this spring when Simon Kaner, a colleague of Fumiko and an archaeologist at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, passed through Montreal. I happened to mention my days at Shanidar, and he immediately informed Graeme that I was still in the land of the living,” explained Philip, who remained in close contact with Solecki until his death in 2019 aged 101.

“Alas, since Shanidar Cave I have found no more Neanderthals. I have always felt rather possessive about those two and was distressed to hear rumours that they vanished during the looting of the Baghdad National Museum in 2003. Fortunately they seem to have survived safely according to Graeme and Emma and are now on display in the museum.”

In May this year, Professor Barker and Dr Pomeroy, who is External Director of Studies in Archaeology at St John’s, returned to the cave with colleagues for the first time since the pandemic began to continue their work.

Re-studying the Solecki Neanderthals in Baghdad Museum is a key research aim for Dr Pomeroy, who was an undergraduate and PhD student at St John’s and is now a Fellow at Newnham College. She said: “Shanidar Cave is an iconic site I learned about as an undergraduate at St John’s and I never dreamed I would ever get to visit, let alone excavate and study Neanderthal remains from there. It was a really wonderful surprise to be put in touch with Philip and to talk to him about his recollections of working at Shanidar Cave in the 1950s, as well as his memories of finding two such important Neanderthal skeletons.

“To discover a connection to St John’s was even more of a surprise, and it was a real privilege to be able to show Philip and his family the work we are doing with the new Neanderthal remains from Shanidar Cave.”

In 2021, Professor Barker, Dr Pomeroy and their international team of archaeological scientists were awarded the annual Antiquity journal’s prize for the best paper of the year for their outstanding research into the new Neanderthal remains, which are closely associated with the ‘flower burial’ at Shanidar Cave and part of a cluster of associated burials that is unique in Neanderthal archaeology.

Published: 16/06/2022