Quatercentenary of the Old Library

This exhibition marks the four-hundredth anniversary of the completion of the building of the College's Old Library.

When St John’s College was founded, in 1511, its founding statutes decreed that there should be a library. The College’s original Library was situated on the first floor to the left of the Great Gate. The Tudor arches of its windows survive to this day.

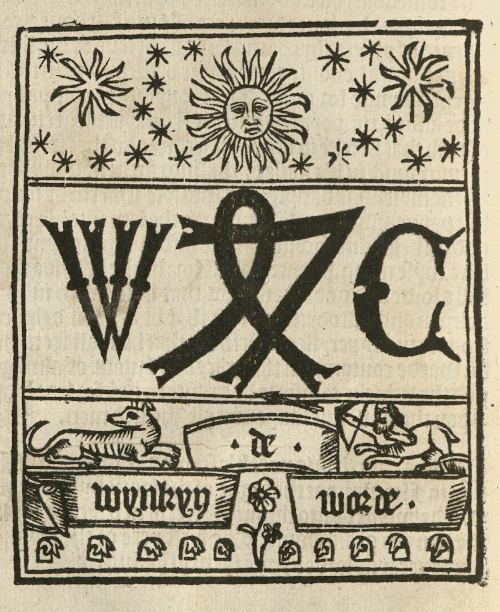

The Library was about nineteen feet wide, and its fittings included seven lecterns on each side, with oak desks made by Thomas Loveday of Sudbury, who had previously made the desks for Pembroke College’s library. It was furnished in 1516, but books were already being bought from the very start of the College’s foundation. A document in the College Archives, now too fragile to display, records Bishop John Fisher, executor of Lady Margaret Beaufort’s will, purchasing books from the printers Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson, both of whom had enjoyed the patronage of Lady Margaret Beaufort. The texts which were purchased were fairly standard: John Chrystostom, Bernard of Clairvaux, Origen, Cyprian, a chronicle, Richard Middleton, and Robert Holcot’s Super sapientiam.

Bishop Fisher intended that his own personal library should come to the College on his death. The Library certainly had expansion space, albeit probably insufficient to take the whole of Fisher’s collections. However, the problem of accommodating them did not arise, as his disgrace meant that the promised books were never to come.

The College’s 1524 statutes decreed that the books should be chained, and ordained that all those proceeding to M.A. should be publicly examined in Aristotle. Lectures on Hebrew or Greek scriptures were included in the 1530 statutes. Royal Injunctions in 1535 took canon law out of the curriculum and directed that divinity lectures were to concentrate on the Old or New Testament. Students in other subjects were to study logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, music and philosophy. Aristotle, Rudolphus Agricola, Melanchthon, and Trapezuntius were the set authors. College Statutes of 1545 required those proceeding to M.A. to be examined in Galen in addition to Aristotle, and listed Greek authors who should be studied: Isocrates, Xenophon, Plato, and Demosthenes. Shelf-lists of 1544 and 1557/8 suggest that the Library possessed few of the set texts and authors laid down in its own statutes. Students or their Tutors must have supplemented central provision with personal collections.

This illustration of the much larger library at the University of Leiden, printed in 1617, demonstrates how books would have been accessed in an academic library of this period. Books were far too valuable a commodity to allow students to take them away. They were to be studied in situ, safely attached to their shelf by a chain.

Early shelf-lists show that the collections grew only slowly, until 1615 when William Crashaw’s substantial library was offered to the College.

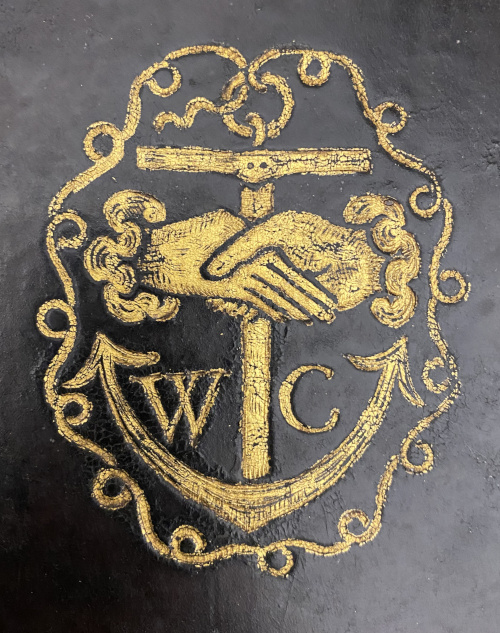

The religious controversialist and poet William Crashaw had built up an impressive and eclectic gentleman’s library while serving as preacher to the Inner and Middle Temples in London. He even went to the expense of extending his official lodgings to house it. However, in 1615, due to tensions between himself and his employers, he was forced by his financial and family circumstances to move away from London. After offering his books to the Temple and to the Royal Library, some 200 manuscripts and 1,000 early printed books were lodged with the Earl of Southampton, also a Johnian, who oversaw the gift of the collection to their old Cambridge College. It was the size of this donation that precipitated the building of the Old Library at St John’s.

A prominent courtier of Elizabeth I, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624) was a major literary patron, including amongst his protégés John Nashe, Gervaise Markham, Barnabe Barnes, and most famously Shakespeare, whom he supported for a year or so in 1593-4. There are even suggestions that he was the addressee of Shakespeare’s Sonnet cycle. Later in life he was associated with the Earl of Essex’s rebellion against the ageing Queen for which he was imprisoned and narrowly escaped execution. After James I’s accession he was rehabilitated for a time, and was able to build up sufficient wealth to become a major sponsor of the colonization of North America, as a member of the Virginia Company. He was responsible for the transfer of Crashaw’s collection of printed books to St John’s in 1626, although his son, the 4th Earl, held onto the medieval manuscripts until 1635.

The offer of Crashaw’s substantial library meant that alternative accommodation had to be found for books. A new building was required, and St John’s responded as Colleges have ever done: with an appeal to its old members for funds to build. An approach to the Countess of Shrewsbury, who had supported the building of Second Court, was unsuccessful, but John Williams, the Bishop of Lincoln and Keeper of the Great Seal responded with great generosity. Initially, he preferred to keep his benefaction anonymous, and negotiated with the College through an intermediary. He was eventually persuaded to be acknowledged publicly as the founder of the Library. His initials ILCS, (Iohannes Lincolniensis Custos Sigilli) appear in stone letters high on the building overlooking the river.

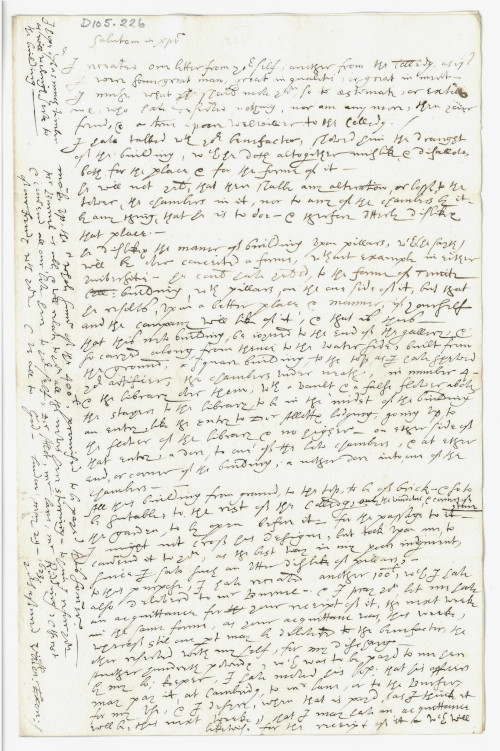

Negotiations with John Williams were carried out on the College’s behalf by Valentine Carey, Bishop of Exeter. A letter from Carey to the Master of the College, Dr Gwyn, written on 29 May 1623, outlines his discussions with the benefactor, at that stage unnamed, regarding the proposed building. He disliked the idea of a building upon pillars, as this was ‘too conceited a form’ and would not fit the surroundings. He suggested that the new building should be ‘joined to the end of the gallery and be carried along from thence to the waterside’. It should be square from the bottom to the top and built of brick to match the rest of the College, with windows and corners of stone. It should have chambers underneath and library above. The building was constructed to this specification.

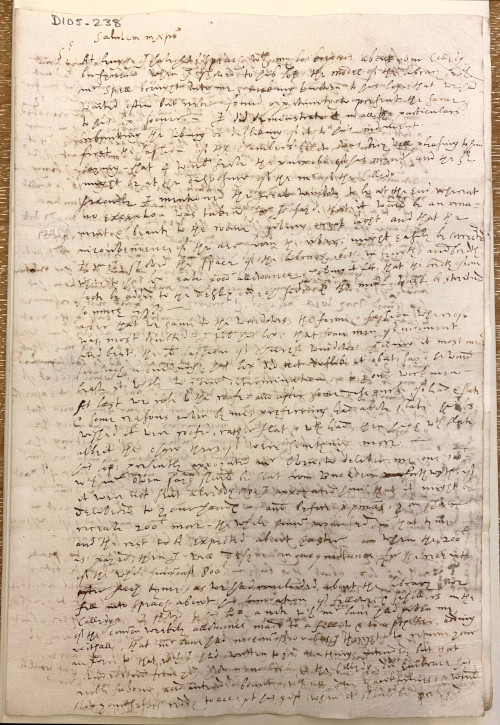

A letter from Valentine Carey to the Master, preserved in the Archives, confirms Williams’s approval of the new plans for the Library. Carey reports that he has spoken to ‘my Lord Keeper’ (now acknowledged as the donor) and presented him with plans of the Library to discuss in detail. His Lordship was very well pleased with the fashion of the chambers below the Library. The great window at the end also met with approval, agreeing that it would be an ornament and beauty to the room, giving great light, and that the inconvenience of the air from the river might safely be corrected. The form of the windows was also discussed, it being thought that the fashion of church windows was most meet for such a building. Williams did not dislike the idea, but said that he would leave it to the determination of the Master and his workmen. More argument was had over the roof, where Williams preferred lead above slate. The letter then deals with financial arrangements, and some talk about his foundation of fellowships and scholarships.

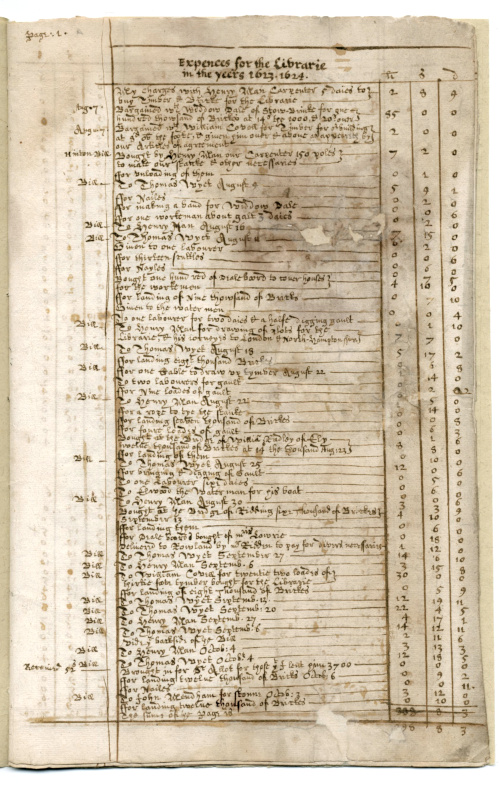

The expenses for the building of the Library have also been preserved in the College Archives. The first page of this document outlines some of the expenses incurred in 1623-4. The carpenter Henry Man features prominently, as does Thomas Wyet. Thousands of bricks are brought in by river for construction.

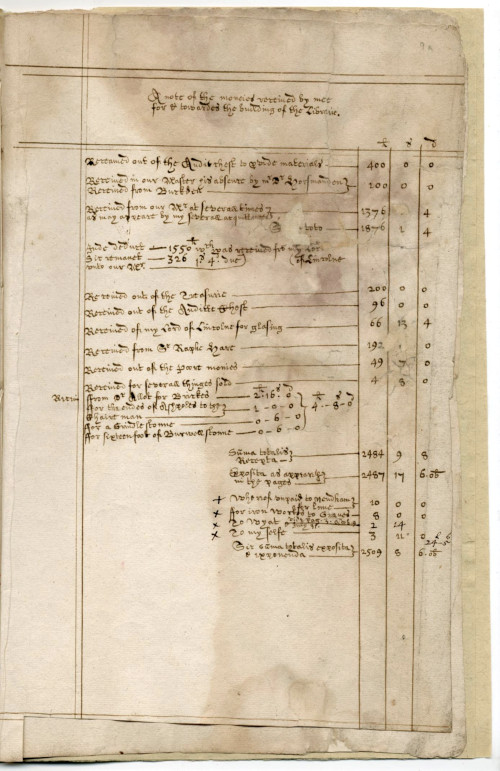

The final page of these accounts give the totals for receipts and expenses relating to the Library. My Lord of Lincoln, i.e. John Williams, is listed as providing £1550, and then also paying a further £66 for glazing. Williams took a keen interest in the design of the building. Ralph Hare, a Fellow of the College, also gave £192. The sum total was over £2500, a vast amount of money for the time.

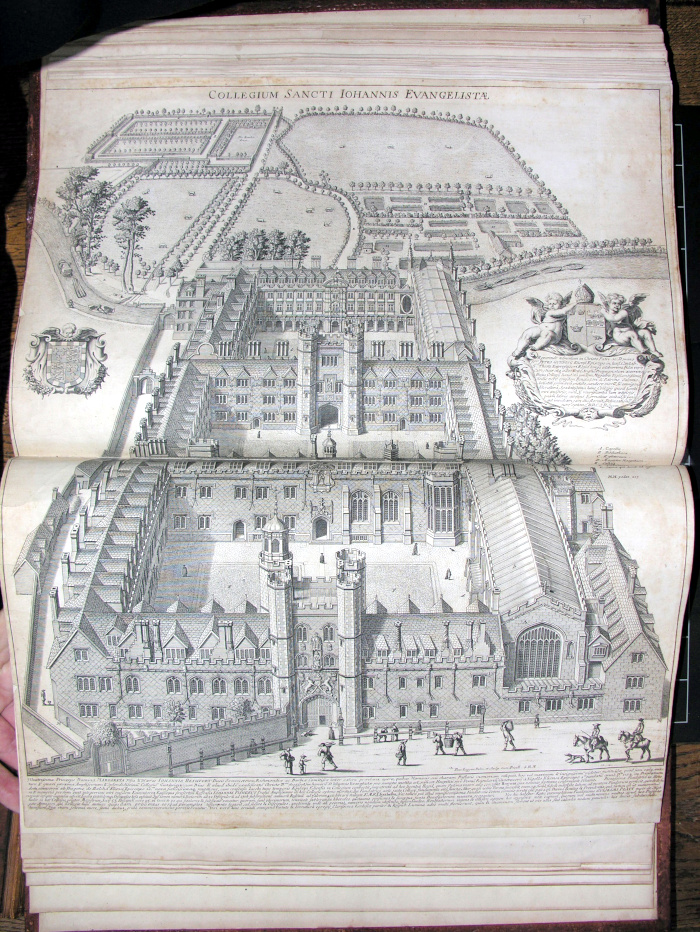

David Loggan’s print of 1690 shows the locations of both the College’s first Library and the 1624 building. The arched windows on the first floor to the left of the Great Gate indicate the original Library facing on to St John’s Street. Beyond First Court can be seen Second Court, built at the very end of the sixteenth century. The new Library stretches down the right-hand side of Third Court, with the remainder of that court being added in 1671.

So, by the early seventeenth century, the College had extended to two courts: First and Second. The south range of the new Second Court was occupied along its first floor by the Combination Room, a grand long gallery and entertaining suite, then part of the Master’s Lodge. Important rooms were typically on the first floor, and the new Library was adjoined to the end of Second Court (later in the century to become the first side of Third Court), appropriating a little bit of the Combination Room ceiling in its lobby. The location meant that when the great and the good were entertained in the Lodge, they could easily be taken across the landing to view the College’s magnificent new Library.

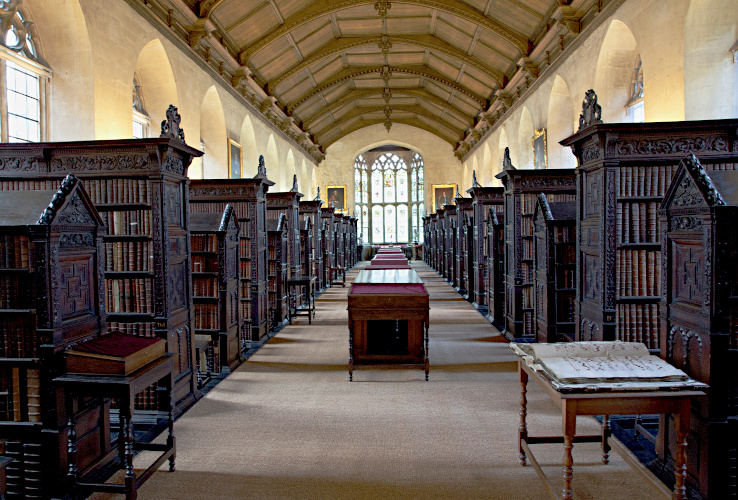

Magnificent it certainly was. Designed in the Jacobean Gothic style, its bookcases were made of oak, exquisitely carved by the workshop of Cambridge carpenter Henry Man. Large cathedral-like windows provided ample light for reading at the lectern-topped dwarf bookcases which provided standing height desks in each bay of the library. At 110 feet long and 30 feet wide it was the largest library in Cambridge at the time that it was built. It was built to impress, and its scale shows the importance that the College placed on books. The existing collections, plus Crashaw’s would have totalled maybe around 2000 volumes. Admittedly some additional shelving was added in the eighteenth century, but there are now around 30,000 volumes housed there. Clearly those planning the building foresaw a great increase in the acquisition and use of printed books. They were right to do so. The seventeenth century saw a huge increase in publishing.

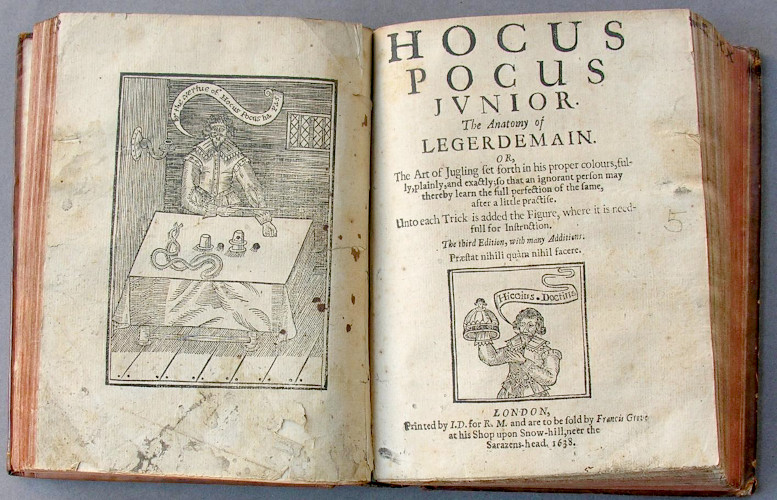

The College saw a large and well-stocked library as essential to a scholarly institution. Once it had built its ‘treasure house’ it called upon its alumni to help with filling it. Johnians responded to that call with generosity and enthusiasm, giving the College a wide variety of volumes. The Library has always been in essence an assemblage of gentlemen’s libraries: reflecting the personal interests of the well-educated classes, rather than the academic syllabus of the University. At the time that concentrated on theology, mathematics, and classics. These subjects were well-represented, but stood shoulder to shoulder with medicine, philosophy, and history, plus works of literature, a wide range of languages, exploration and travel, sciences and pseudosciences, even a book of magic tricks.

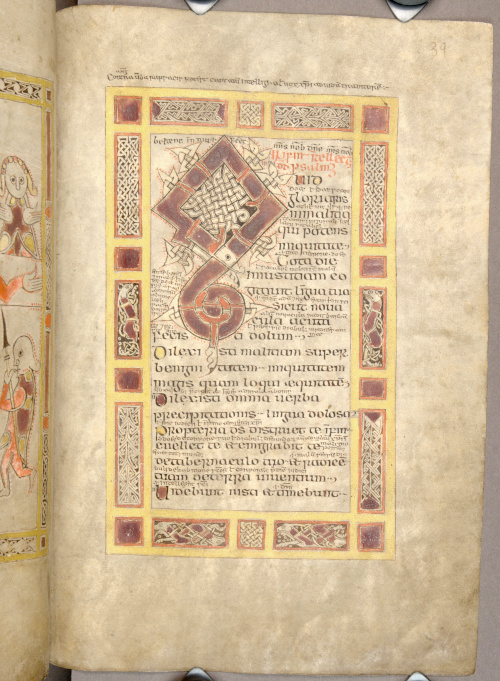

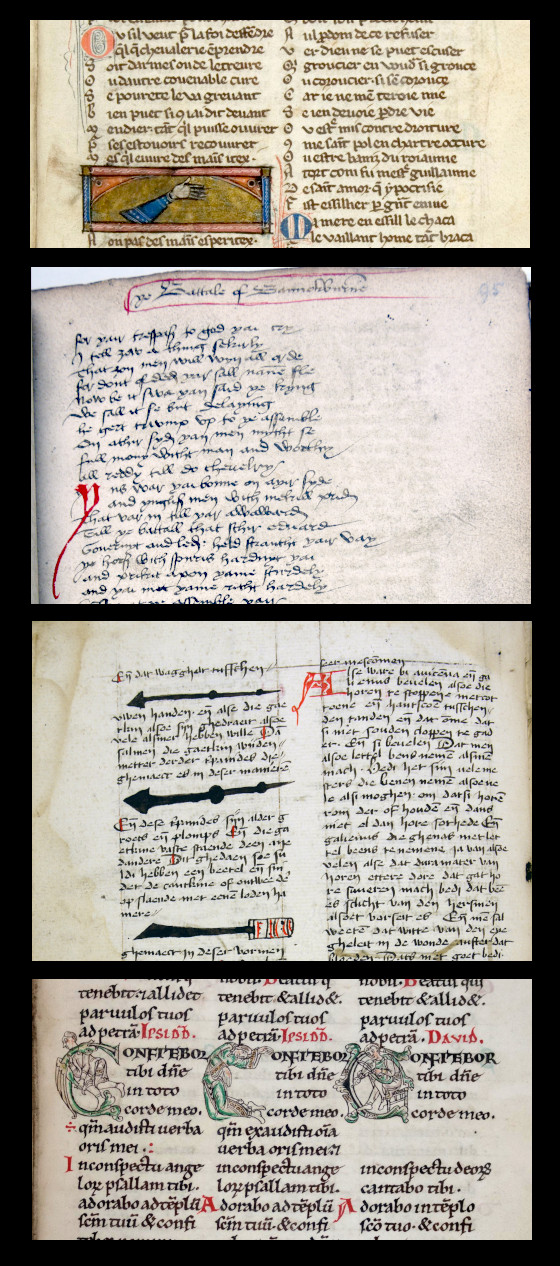

William Crashaw’s donation brought to the Library many of its most significant early treasures including the two oldest manuscripts in the College’s collections, both of which date from the tenth century. MS C.9 is a book of psalms, known as the Southampton Psalter, which is particularly special in that the glosses on the Latin text are not just written in Latin, but also in Old Irish, providing a rich resource for scholars of the language. Its decoration is stunning, with a palette of purple, orange and yellow. Initials intertwined with dragons and other strange creatures, intricate celtic knotwork borders, and three full page illustrations provide ample material for art historians.

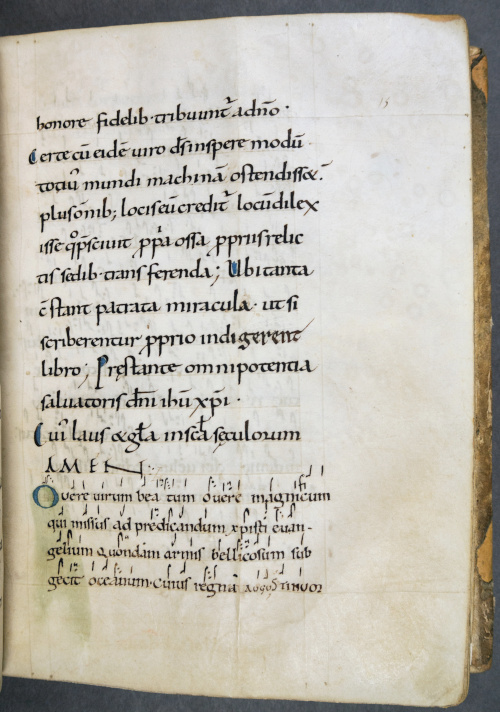

MS F.27 is perhaps lesser known, lacking the exuberant decoration of C.9, but was also produced in the tenth century. Containing a text of Saint Benedict, this manuscript came from the scriptorium of St Augustine’s in Canterbury. It is special in containing neumes, a very early form of musical notation.

William Crashaw also provided the Library with its earliest printed book. Bound together with a manuscript, his edition of Cicero’s De Officiis was published in Mainz by Fust and Schoffer in 1466, just eleven years after the Gutenberg Bible was the first book to roll off the printing press in Europe.

![Final page of the Library's earliest printed book, with publication details in red. [Bound with MS F.19]](/sites/default/files/public/Colophon.jpg)

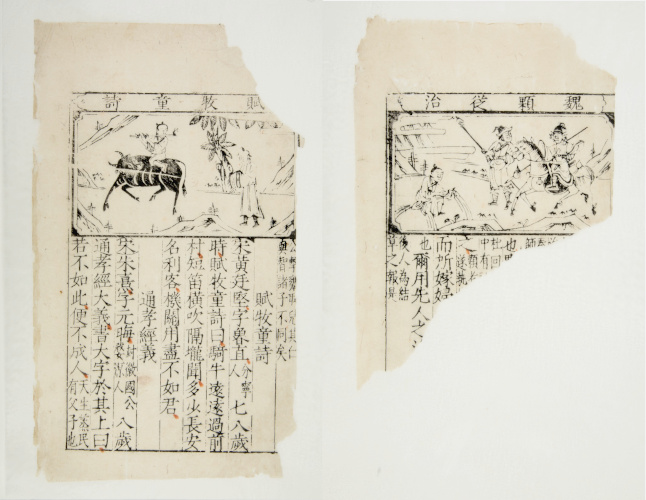

Our oldest printed book in Chinese, commercially published in Fujian and dating from around 1600, also came from Crashaw’s collection. It was described in a shelf-list of 1635 simply as ‘a booke in China language’. It must have been bought solely for its decorative appeal, as Crashaw would not have had the language skills to read it. It is a reprint of daily stories ~ Chongkan riji gushi ~重刊日記故事 : an illustrated reader of moral tales, aimed at a juvenile readership. The book is woodblock printed throughout. Incomplete, and in very poor condition having clearly spent some time without a cover before being uncomfortably inserted into a western binding, it has been disbound for conservation and is now fully digitized, so that scholars may study it without handling the extremely fragile pages.

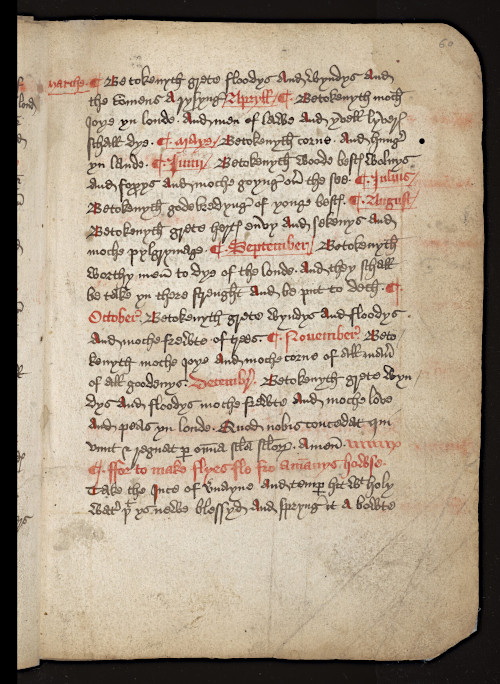

The College’s medieval manuscripts collection spans many centuries, a range of subjects, and diverse languages and places of origin, but more of the manuscripts came from William Crashaw’s library than any other single source, including a range of subject matter, language, and place of origin. Thanks to Crashaw we have works of medieval French literature, Scottish history, a herbal from Syon Abbey, a Flemish surgeon’s manual, and many religious manuscripts: Bibles, psalters, and devotional works.

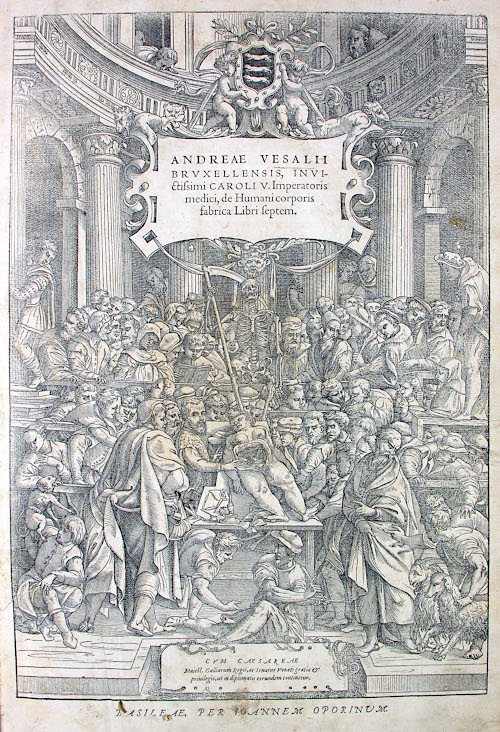

The completion of the new Library in 1628 prompted further donations from a wide range of Johnians. One of the most significant collections to come to the College at this time was that of John Collins. Collins studied at St John’s in the 1590s before studying for his MD and then returning to the College as a Fellow, becoming Regius Professor of Physick in 1626. On his death in 1634 he was buried in the College Chapel. He left all of his medical books to St John’s together with £100 for the purchase of further volumes. Over 300 works with his provenance are to be found in the Library, including eight medical incunabula, the oldest being Savonarola’s De pulsibus, urinis, et egestionibus of 1487. Evidence of the influence of Arabic medicine during the 15th and 16th centuries may be found in a Venetian edition of Razi’s works of 1497 and a Lyon edition of Avicenna’s Qanun from 1498. His books cover every aspect of contemporary medical knowledge, including surgery, pharmacology, and numerous illustrated works on anatomy. It is thanks to Collins that the College owned contemporary editions of works by Vesalius and Falloppio. Collins’ donation was in fact quite out of proportion to the scale of teaching in medicine at a time when the University as a whole admitted only one or two students per year to read medicine.

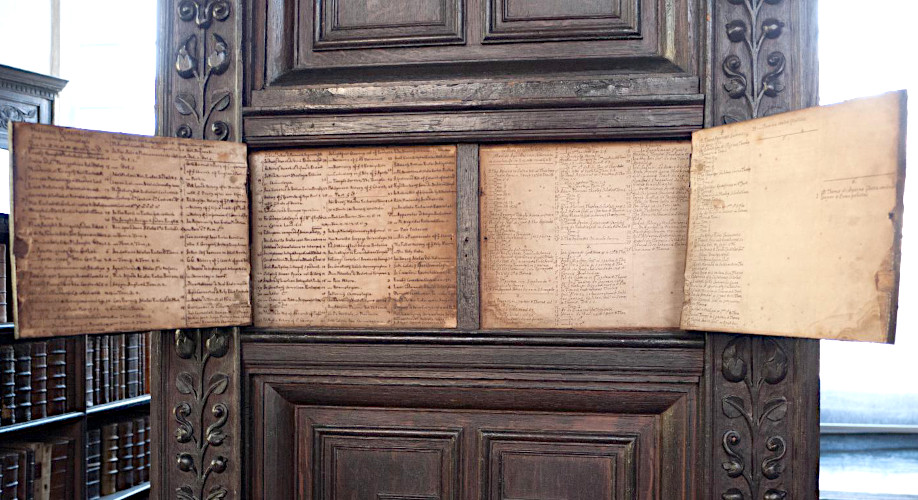

The Library was designed for practical use. Not only did the smaller bookcases provide well-lit desk space, the taller cases provided access to useful finding aids. A list of the books in each class was pasted into compartments on the ends of each case.

Books were arranged in approximate subject groupings. Their shelf-mark reflected a precise physical location (very much as ‘what three words’ does today). Each bay or class was allocated a letter (single letters on the north side, and double on the south), then each shelf had a number, and each book had a number. So if the book you wanted to read had the shelf-mark O.2.10 you would go to class O, shelf 2 and take the 10th book along the shelf (John Fisher’s refutation of the theology of Martin Luther, published in 1523, and bound by the Cambridge bookbinder Garrett Godfrey).

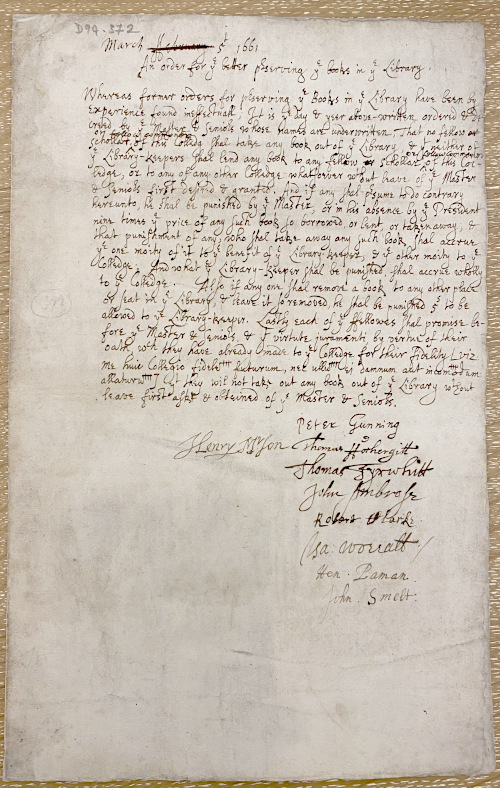

By 1690 maintaining the lists of books on the end of each tall bookcase had become too cumbersome a job. More books were arriving and being moved around and this was no longer a practical way to record their locations. Ledgers were employed for each class, and the shelf-lists sealed up, to preserve a snapshot of each class at the time. Little evidence survives of the practical management of the Library in the 17th century, but an Order for the better preserving of the books in the Library of 1661 remains in the College Archives. Describing previous orders for preserving the books as ‘ineffectual’, this order requires that any Fellow, Fellow Commoner or Scholar wishing to borrow a book should first obtain the permission of the Master and Seniors. Anyone removing a book without such permission would be fined nine times the price of the book, half of the fine to go to the Library Keeper and the other half to the College. If the Library Keeper removes a book, his fine would go entirely to the College. Anyone moving a book to another location within the Library and not reshelving it in its proper place afterwards would be fine five shillings, all to go to the Library Keeper. Fellows were required to promise on oath that they will not remove a book without first seeking permission to do so. The draconian tone of this order suggests that the College had found it very hard to keep tabs on the whereabouts of the books to date. Now permission was to be required, oaths must be sworn, and hefty penalties were imposed upon those who contravened the regulations. (If students were fined now for leaving books lying around, the librarians would be rich!)

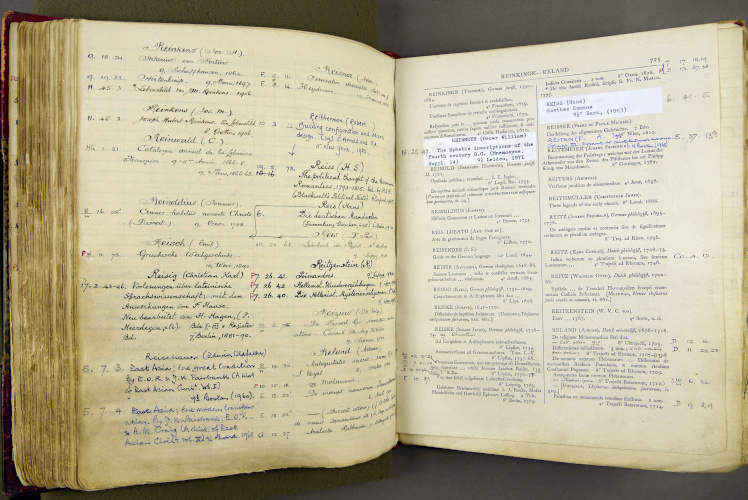

As the Library’s collections grew, it became harder to find specific titles. A catalogue searchable by author or title was needed. A printed copy of the Bodleian Library’s catalogue was used, first that published in 1674, which was used up until around 1763, and then the edition published in 1738. Entries which matched books in St John’s were annotated with the local classmark, while interleaved blank sheets were provided to add titles that were not in the printed catalogue. In 1892, the Library switched to using the printed catalogue of the Library of the Faculty of Advocates in Edinburgh, 1863. This continued to be the only catalogue for the Library up until the 1980s when a computerized catalogue was begun. Works housed in the Upper Library were only recatalogued online in the early 2000s: a task which took eight person-years to complete. We are grateful to a generous benefactor, Joseph Zund, who contributed financial support to the recataloguing project.

The collections in the Library continued to grow throughout the early part of the eighteenth century. By the time that Thomas Baker, bibliophile, antiquarian, and - thanks to his non-juring principles - ejected Fellow of the College came to the end of his long and learned life, there was insufficient space to house the bequest of his very substantial personal library. The dwarf cases with lectern tops were raised in 1740 to create the necessary shelf space, just one pair at the east end being left at their original, usable height.

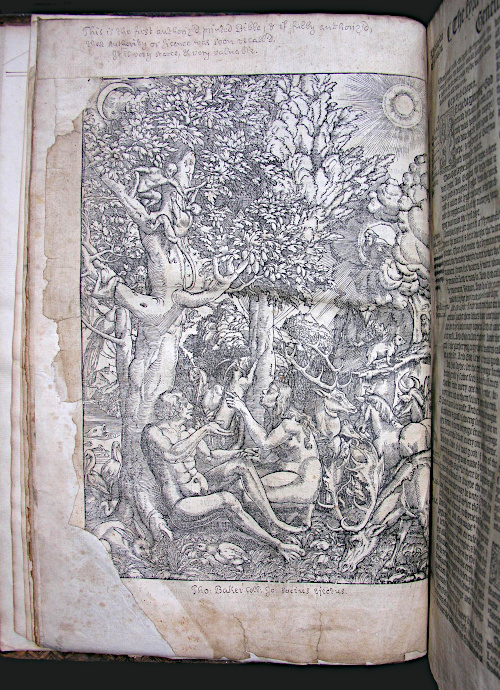

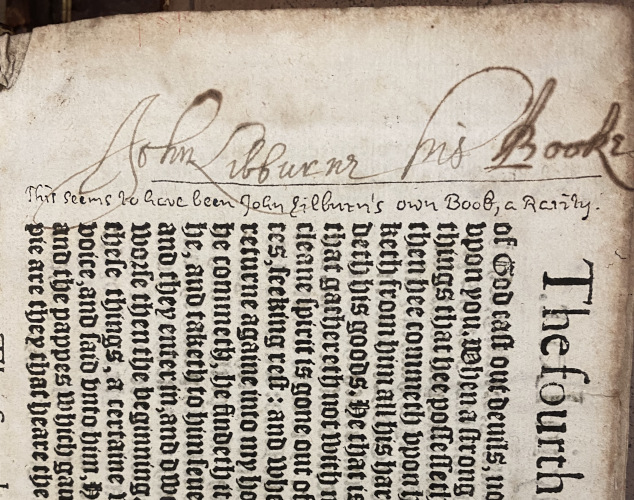

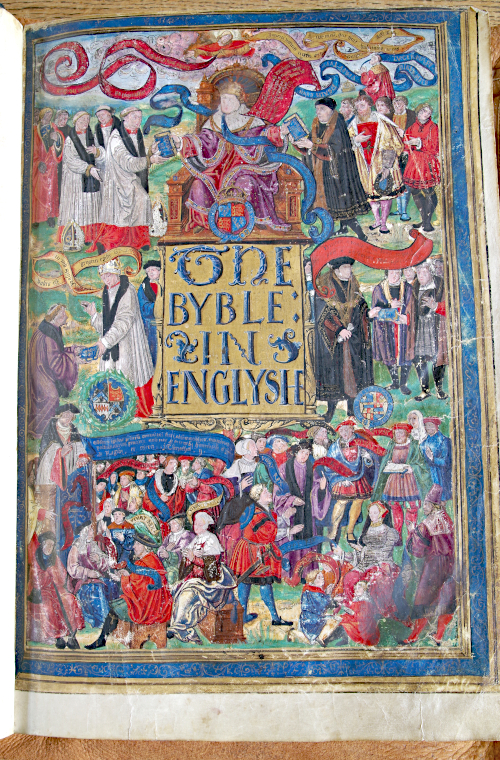

Baker collected many valuable early editions, particularly relating to the history of church and state. Where he could only afford to buy imperfect editions, any missing text was supplied in his own distinctive hand. The Library owes its two earliest English Bibles to Baker, along with works published by Caxton, a book from the library of Elizabeth I, a first edition of Foxe’s Book of martyrs, a manuscript copy of sonnets by William Alabaster not published in the poet’s lifetime, and a multitude of other fascinating and historically significant works. Many of Baker’s donations contain a book label detailing his bequest. Translated it reads:

From the gift of the Reverend Thomas Baker BD who was once a Fellow of this College: afterwards in truth, having been expelled by decree of the Senate, he grew old as a guest in this house; of blameless life and celebrated reputation, which followed from his study of antiquity.

In Thomas Baker’s copy of the Matthew Bible published in 1537, his note at the head of the full-page illustration of the Garden of Eden states ‘This is the first authorized printed Bible, & if fully authorized, that Authority or licence was soon recall’d. It is very scarce, & very valuable’. At the foot of the page is Baker’s typical ownership inscription ‘Tho: Baker Coll: Jo: Socius ejectus’. This copy is imperfect, lacking all of the first quire, including the title page. Omissions are supplied in manuscript copy by Thomas Baker.

By the mid-nineteenth century the Upper Library’s shelves were completely full. More space was needed, and rather than raise the shelves again, the Library expanded downwards, to begin to occupy the space on the floor below. In 1858 a metal spiral staircase was installed to give access to the room at the west end of the building. By 1902, all of the sets formerly used for accommodation beneath the Library had been colonised.

Both the Old Library building and its books continue to be used regularly. It is no longer a practical study space - the absence of desks, powerpoints, adequate lighting or heating mean that it is not a suitable work area. It is, however, a space in which classes can be held, both for University students and visiting school parties. Visiting special interest groups come to see material relating to their area of interest.

Regular public exhibitions are displayed in the Upper Library for Open Cambridge and Cambridge-wide festivals, enjoyed by hundreds of visitors. A display of treasures from the collections is mounted each year for students and their families on Graduation Day.

The building may be four hundred years old, and some of its contents older still, but it is still a working library. Books are consulted regularly, no longer in situ, but in a purpose-made reading room on the Ground Floor, with appropriate book supports, lights, powerpoints, wifi, and all the resources and facilities needed to preserve the materials and aid researchers.

Now that so many of the texts published before 1800 can be found in digitised form somewhere online, researchers’ interest tends not so much to be in the text itself, but in the history of the book as an object: its provenance, unique manuscript matter contained within it, its marks of ownership, physical construction, binding, pastedowns, and endpapers.

In 2005 the Old Library gained MLA (now Arts Council) Designation, which recognised the national and international importance of its collections, held in trust for public benefit, as an essential research resource which makes a major contribution to public understanding. Designated institutions commit to the good conservation, management, and governance of their collections, and to the accessibility of those collections to researchers and to the public. Designation, of course, opens doors to relevant funding schemes, and the Library has already benefitted from two major grants from the Heritage Lottery Fund to conserve and catalogue important collections and to develop outreach activities.

Scientific analysis is revealing new evidence of the history of some volumes, particularly medieval manuscripts. Pigments can be analysed using a variety of techniques: infra-red, RAMAN, and x-ray fluorescent spectroscopy. Non-invasive techniques can be used to shed light on the history of the parchment itself, using DNA analysis of tiny rubbings from the surface to determine the type of animal used to make the parchment and to learn more about the techniques of its manufacture.

Over the coming months, the Library will be involved in the AHRC-funded project, Hidden in Plain Sight: Historical and Scientific Analysis of Pre-modern Sacred Books, led by Dr Eyal Poleg of QMUL, examining the pigments and DNA of Henry VIII’s Great Bible and similar books of the era.

Meanwhile, having already conserved, catalogued, and digitised 8 of St John’s medical manuscripts, the Curious Cures project, based at Cambridge University Library, will be training an Artificial Intelligence (AI) system to recognise medieval scripts and thereby produce transcriptions of the medical recipes that they contain.

All in all, it looks like the next 400 years in the Old Library’s history will be at least as interesting as the last.

Kathryn McKee, Former Sub-Librarian