Prehistoric chefs’ culinary skills revealed after discovery of ancient charred food

Flavour was important for Neanderthal and early modern humans up to 70,000 years ago, say archaeologists

Analysis of the oldest charred food remains ever found has revealed some of the cooking tricks used by early modern human and Neanderthal chefs to make their meals more palatable.

The archaeologists also found that prehistoric people had a diverse diet in which plants played a major role. Research has often focused on the importance of meat in the diet of ancient hunter-gatherers. However, Dr Ceren Kabukcu and a team of archaeologists wanted to explore the role of plants in the diet of Palaeolithic humans and Neanderthals.

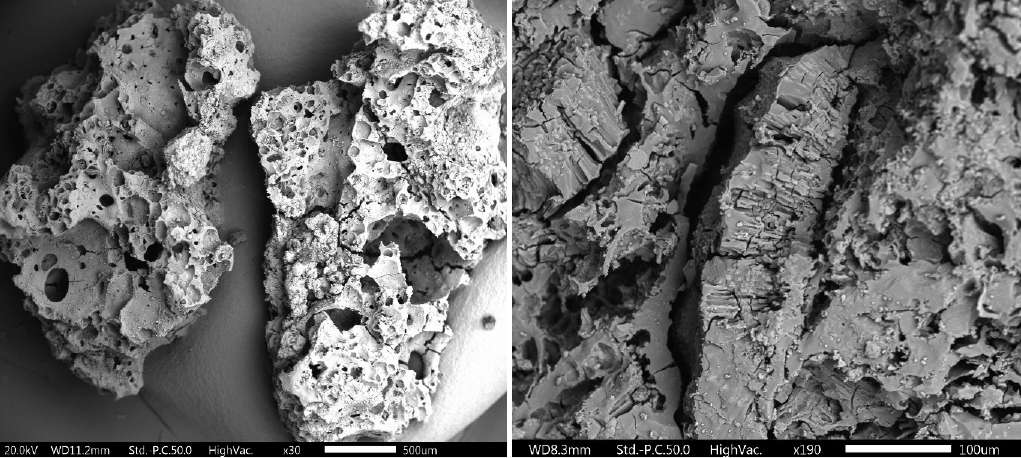

To investigate this, they used a scanning electron microscope to analyse ancient charred food on the micrometre scale. The samples came from early modern human and Neanderthal occupations at Shanidar Cave, Iraq, where excavations are led by Professor Graeme Barker – Disney Professor of Archaeology Emeritus, Senior Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research and Fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge – and Franchthi Cave, Greece. Together, this material captures food preparation techniques used over the past 70,000 years.

“The charred food fragments from Franchthi Cave are the earliest of their kind recovered in Europe, from a hunter-gatherer occupation around 12,000 years ago,” said Dr Kabukcu, an archaeobotanical scientist from the University of Liverpool. “Those from Shanidar Cave are the earliest in Southwest Asia, from Neanderthal and human layers dated to 70,000 and 40,000 years ago respectively.”

The results of this analysis, published today in the journal, Antiquity, confirmed that plants played a prominent role in the diet of early modern humans and Neanderthals.

The Shanidar Cave team, which also includes Dr Emma Pomeroy, External Director of Studies in Archaeology at St John’s College, Professor Chris Hunt from Liverpool Moores University, Dr Tim Reynolds of Birkbeck, University of London, and Evan Hill from Queen’s University, Belfast, is uncovering new deposits from Mousterian levels, and new skeletal remains of Neanderthals. They are now able to provide new evidence on the development of plant foraging and fuel use through the long period of use of the cave by Palaeolithic humans.

“Our work conclusively demonstrates the deep antiquity of plant foods involving more than one ingredient and processed with multiple preparation steps,” said Dr Kabukcu. Wild nuts and grasses were often combined with pulses, like lentils, and wild mustard.

The team was even able to identify some of the techniques used to prepare this food to make it more palatable. Pulses, the most common ingredient identified, have a naturally bitter taste due to the tannins and alkaloids in the seed coats. However, Palaeolithic chefs used a range of tricks to lower the amount of these harsh-tasting compounds in their food.

“Their preparation through soaking and leaching followed by pounding or rough grinding would remove much of the bitter taste,” said Dr Kabukcu.

Pounding or grinding would also make it easier for the body to absorb nutrients in the food. It also opens up cooking options – one food deposit from Franchthi Cave consists of a bread-like meal made by grinding seeds into super-fine flour.

Professor Barker said it is interesting that Neanderthals, like ‘ourselves’, were grinding and mashing plant food like seeds, and probably cooking them on hot stones.

He added: “The social role of food has always been regarded as a uniquely human trait and we can see that from the earliest history of Homo sapiens; so the evidence from my excavations at Shanidar Cave that Neanderthals, our closest evolutionary cousins, were cooking food 75,000 years ago pretty much like our own species was doing at the site 35,000 years ago is another piece of evidence for how sophisticated Neanderthal culture was, very far from the bad press Neanderthals have had for so long as the architypal 'cave men/cave women'.”

Neither the Neanderthal nor early modern human chefs removed the entire seed coat. This is a process known as hulling and is common in modern agriculture as it almost entirely eliminates the bitter compounds. The fact the Palaeolithic people did not hull suggests they wanted to reduce but not eliminate the pulses’ natural bitter taste in their meals.

“This points to cognitive complexity and the development of culinary cultures in which flavours were significant from a very early date,” said Dr Kabukcu.

Reference

'Cooking in caves: Palaeolithic carbonised plant food remains from Franchthi and Shanidar' – Ceren Kabukcu, Chris Hunt, Evan Hill, Emma Pomeroy, Tim Reynolds, Graeme Barker and Eleni Asouti: https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.143

Published 23/11/2022