A book full of history

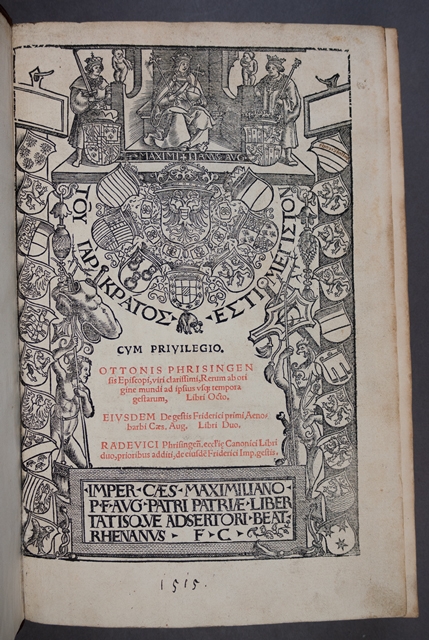

Some of the College’s earliest printed books came to St John’s from the personal library of William Crashaw. The religious controversialist and poet William Crashaw built up an impressive library while serving as preacher to the Inner and Middle Temples in London. Around 1000 volumes from his early printed book collection came to St John’s via his friend and fellow Johnian Henry Wriothesley, earl of Southampton. While canon law and theological subjects predominated, he collected other works too, including this biography of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I. This contemporary account of Frederick’s life was written by Otto of Freising, bishop and close relation of the emperor, who knew the protagonists in his history personally and saw many of the events he recounted at first hand.

Some of the College’s earliest printed books came to St John’s from the personal library of William Crashaw. The religious controversialist and poet William Crashaw built up an impressive library while serving as preacher to the Inner and Middle Temples in London. Around 1000 volumes from his early printed book collection came to St John’s via his friend and fellow Johnian Henry Wriothesley, earl of Southampton. While canon law and theological subjects predominated, he collected other works too, including this biography of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I. This contemporary account of Frederick’s life was written by Otto of Freising, bishop and close relation of the emperor, who knew the protagonists in his history personally and saw many of the events he recounted at first hand.

Although Otto is unfailingly loyal to his imperial nephew, and sets out openly to praise his deeds, his history is not totally lacking in objectivity. He acknowledges the motives of those who chose Frederick to serve as Emperor. His approach to history is biographical, using examples of individuals to highlight virtues. He does not dwell on the disastrous outcome of the second crusade (in which he participated) as his purpose is - self-confessedly - to write a cheerful history. A German speaker, Otto writes in Latin, the common language of European scholars, though occasional evidence of his native language can be seen in his use of local names. He includes rhetorical phrases, proverbs, anecdotes and quotations, and follows the example of ancient historians such as Thucydides in reporting conversations between his key protagonists apparently verbatim, even where the actual words spoken cannot have been known. However, and very helpfully for future historians, he includes copies of original documents such as letters to illustrate his history, and even gives some references to his sources. In comparison with some other medieval histories, Otto’s work provides a valuable and reasonably reliable resource for later historians.

Although Otto is unfailingly loyal to his imperial nephew, and sets out openly to praise his deeds, his history is not totally lacking in objectivity. He acknowledges the motives of those who chose Frederick to serve as Emperor. His approach to history is biographical, using examples of individuals to highlight virtues. He does not dwell on the disastrous outcome of the second crusade (in which he participated) as his purpose is - self-confessedly - to write a cheerful history. A German speaker, Otto writes in Latin, the common language of European scholars, though occasional evidence of his native language can be seen in his use of local names. He includes rhetorical phrases, proverbs, anecdotes and quotations, and follows the example of ancient historians such as Thucydides in reporting conversations between his key protagonists apparently verbatim, even where the actual words spoken cannot have been known. However, and very helpfully for future historians, he includes copies of original documents such as letters to illustrate his history, and even gives some references to his sources. In comparison with some other medieval histories, Otto’s work provides a valuable and reasonably reliable resource for later historians.

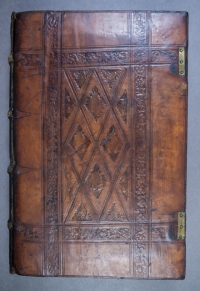

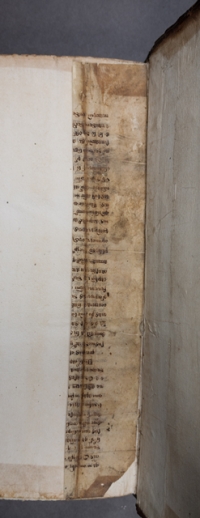

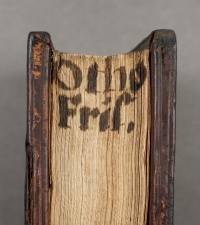

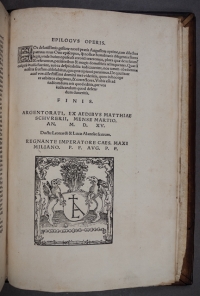

This particular copy of the Gesta Friderici imperatoris was published in March 1515, in Strasbourg, by Matthias Schurer, a publisher who also printed the works of Erasmus. The inked ‘Otho Fris’ on the foredge of the book indicates that it was once shelved with the foredge frontmost, rather than the spine: a common practice in the sixteenth century. The book was bound in London and retains its original blind-stamped binding made of calfskin over wooden boards. As was the case with many volumes of the period, fragments of older manuscripts were used in the construction of the book. Parchment was too useful to be wasted when a manuscript fell out of use and was recycled by bookbinders to create endleaves and pastedowns and to strengthen spines.

A single volume, whose individual story can be traced over the last five hundred years from Strasbourg to London, through Crashaw’s library, via Henry Wriothesley to Cambridge, thus gives us not just a renaissance printing of a much earlier history, but also physical evidence of a completely different medieval text, and of how the book was shelved. Layers upon layers of history…

This Special Collections Spotlight article was contributed on 17 August 2015 by the Special Collections Librarian.