Student involvement

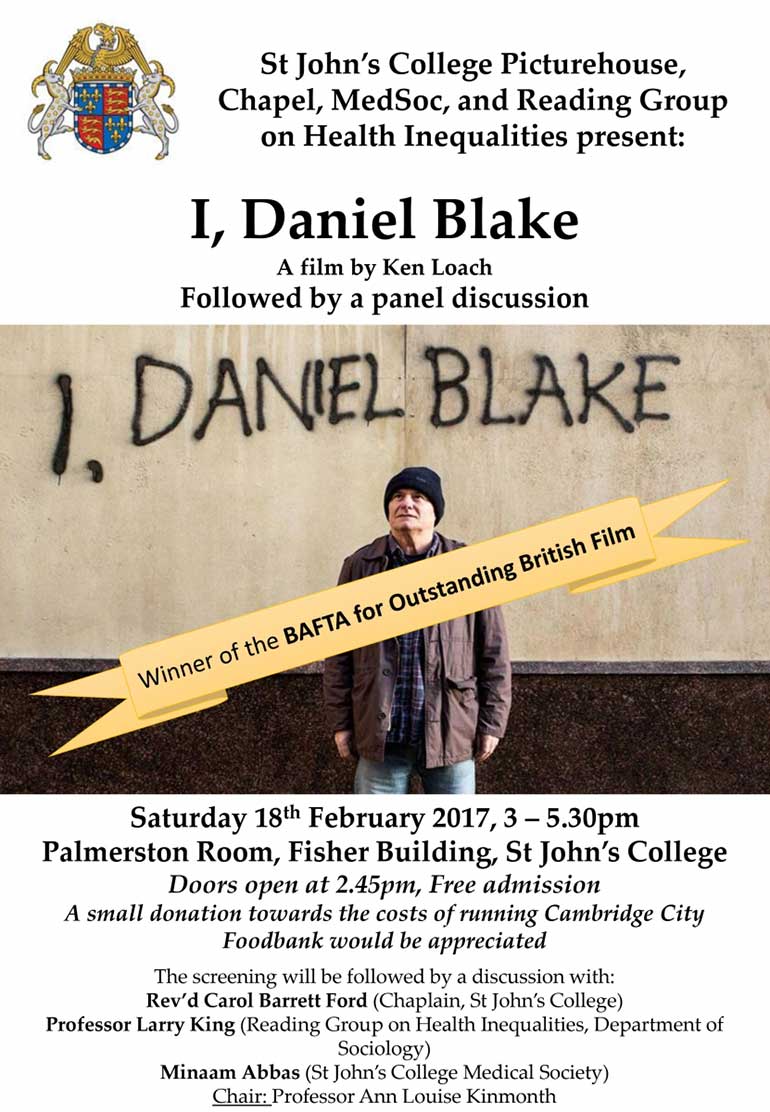

I, Daniel Blake film screening

I, Daniel Blake film screening

The event was sponsored by Chapel and the Reading Group. Admission was free. £150 was raised for the Cambridge City Foodbank.

Commentary by Prof Ann Louise Kinmonth

Between 30-40 people aged from 15 to 93 years old joined this event. I was also 15 when on 16 November 1966 (along with 12 million other people – a quarter of the British population at the time) I watched my first Ken Loach film, Cathy Come Home, on the TV.

As Cathy’s modest dreams of man, home and family fell apart in the face of unemployment, poverty and homelessness and Carol White`s golden halo of hair fell into rat tails, questions were asked in Parliament and the charity Crisis was formed; yet Loach has said that despite the public outcry following the film, it had little practical effect in reducing homelessness.

Watching Daniel Blake slowly realise that a lifetime of hard graft, paying your taxes and being a good friend was not going to qualify him for subsistence support while his heart recuperated, and Katie Morgan realise that there was no safety net for her either as she replaced her dreams of motherhood and study with shop-lifting and prostitution, the pressing question remains what can we as citizens do?

The Rev’d Carol Barrett Ford served her curacy in Newcastle. She began by affirming the authenticity of the film. She had often been in the featured food bank and knew personally the staff who “acted” in that scene. She was also often in the kind of welfare housing that Katie and her two children had in exchange for the social support of her mum and friends in London. Carol described the stock as often dirty and low standard; poignantly we hear Katie on the phone to her mother describing the carpets and fittings that existed only in her imaginative attempts to reassure.

Carol also spoke of the public library full of anxious people who are not, as the jobcentre manager said, “digital by default” but rather as Daniel responded “pencil by default; that’s me”.

This affirmation matters. Former Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith referred to the film as untypical and unfair, aiming particular criticism at its portrayal of jobcentre staff, but failing to consider that the welfare system itself encourages staff to act according to protocol and threatens them with joining those on the other side of the table if they do not toe the line, and master the use of terms such “ the Decision maker”; indeed on Question Time in October 2016, Loach pointed out that he was trying to portray the pressure that DWP staff are placed under themselves.

But it is hard to deny the cruelty of a system that not only minimises the financial support for the poor and ill who have run out of personal and family support, but also makes it unnecessarily difficult to access that which should be in place, and can remove it summarily if a single meeting is missed (the sanctions we saw invoked in the film). Indeed there is a move to counter this, with a pilot study of a whole two week delay for face to face review before sanctions are applied. (Frank Field)

I was particularly concerned that a so called “health professional” hired by a private firm could assess as fit to work a man like Daniel, in possession of certificates of ill health from experts who had studied and practiced medicine for years. There will always be mistakes in assessment, but a humane system will have in place a swift response to identifying and rectifying such errors.

The Department of Work and Pensions statistics of August 2015 showed that death-rates among those declared fit for work by commercial companies such as ATOS were disproportionately high; and a number of them have been suicides.

Carol went on to remind us of the central importance of relationship with respect for and listening to each person, especially when down on their luck and suffering multiple hardships.

The different perspectives taken by citizens on the responsibility of the deserving and undeserving poor for their predicaments, and the number and proportion of each, underlie and inform the policies put into place, to manage unemployment, long term incapacity and homelessness. Where these predicaments are seen as more frequently linked to bad luck and vulnerability and less often to fecklessness and scrounging off the state, we are less likely to view them as resulting from moral deficiencies and more able to imagine anyone of us sometimes needing a helping hand.

Larry showed us data from the British social attitudes survey 2012. At no time since 1983 did more than a few percent of responders want to reduce taxes or spend less on health, education and social benefits. However, it is notable that from 1990 to 2010 the proportion calling for increase in taxes and spend in these areas fell from more than 60 to 20%, with the majority in later years opting for the status quo.

The idea of difficulties arising at least in part outside ones control is central to the concept of universal welfare provision that emerged partly driven by the dreaded effects of harvest failure and which served this country so well from the 17th to the 19th century (Szreter et al, 2016).

Following the two world wars and up until the 1970s the UK became one of the most equal of countries in the world; a position from which we have fled, with rising inequalities in income and wealth a clearly visible long term trend since the beginning of the 1980s and one which the policies of austerity have done absolutely nothing to reverse.

Larry showed us how austerity and rolling back universal, and indeed focussed, welfare was not simply bad for the vulnerable individuals concerned, but bad for the state and the economy.

Drawing on ONS data he showed how austerity has been associated with significantly greater cuts in the more deprived regions; bearing down most heavily on the least resilient.

Larry drew our attention back to the 1930s and considered the economic management of the great Depression in the USA and the ideas of the British economist John Maynard Keynes, presented in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Keynes, 1936).

Larry argued for the importance of keeping total spend in the economy up during periods of recession to limit economic contraction and enable faster economic recovery, and for the central place of the State in achieving this (Stucker and Basu, 2013).

He showed us correlational data linking increase in public spending with faster economic recovery at the national level.

So if public spending can shorten a recession and improve economic performance; while austerity has the opposite effect, bearing down most heavily on the poor and increasing wealth and health inequalities, why vote for austerity?

Larry suggested that it depended on your political beliefs; where you stood; what you understood and the time horizon of that understanding. Austerity might be the choice of politicians supporting unregulated capitalism and advocating trickle down effects. Others will argue that this is a choice for the few with the most now, and not for the nation as a whole over a long term.

Minaam began by describing his first clinical year attachment in a local GP practice and the adverse effects of poverty he saw on personal health and mental wellbeing. He noted the crucial role that GPs could play in tailoring consultations to improve health outcomes among the vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society.

Minaam contended that doctors have a duty to safeguard the wellbeing of their communities as well as their individual patients and that the most significant way to ensure this would be to address the wider social determinants of health inequalities; to practice community orientated primary care medicine.

He also argued the need for a strong counter narrative across multiple media to dispel the persistent myths surrounding welfare use and to re-establish confidence in the need for safety nets to protect the most vulnerable in society. Minaam urged the audience to envision and develop innovative and sustainable local solutions to tackle inequities in their communities.

General Discussion: So what can we do?

We took comments from the audience and from the panel members as to not only what we could take away from I, Daniel Blake, but also what people could do to help.

At an individual level

An educated user of the welfare system who had been sanctioned on several occasions described the huge challenge of navigating the system on-line.

-Those of us who can could volunteer to help fill out forms?

A number of comments referred to the limited knowledge and uncertainty we have about the evidence underlying the film.

-We can educate ourselves about the history of welfare (e.g. Szreter et al, 2016) and political economy (e.g. Stuckler and Basu, 2013).

-We can be unafraid to share our views individually and listen carefully to others of different persuasion.

Someone who had sat in on an appeal for welfare reported how ignorant the decision makers could be about illness and its functional impact

-Those of us who are properly trained practitioners can be aware of the links between welfare and health and be prepared to intervene across the health welfare divide.

Several people contributed to a discussion about the responsibility of the individual for their predicament, and of the culture of dependency engendered by big industry over years; leading to helplessness when such industry closes

At an institutional and work place level

Larry called upon us to organise (see Figure 3) showing the strong general association between union membership and social spend across a range of countries.

Minaam called upon us to develop collective responsibility and leadership to tackle inequalities, including:

- Promote social entrepreneurial approaches in the vein of ventures such as Feeding Forward, Food Cycle etc.

- Increase awareness through further panel discussions, debates and screenings with an emphasis on engaging the student community

- More opportunities for Medical students to recognise the social determinants of health inequalities during placements and develop personal and institutional strategies that may be used to address these.

Interaction with the media

We need to hold the media accountable for sensationalist reporting that vilifies the most vulnerable.

We need to advise them in the use of numbers; how many benefit scroungers are there? What proportion of those on benefit do they comprise?

For every benefit scrounger identified, how many vulnerable people are misidentified as scroungers and sanctioned?

Contribute to Op-eds and opinion pieces to present a counter narrative.

Engage in public debate over social inequalities.

At a political level

We can choose whom we vote for, hold them individually to account and consider the work of the relevant select and all party committees with a critical eye.

Conclusion

As Simon Szreter Professor of Modern History and Fellow of St Johns writes in his companion piece to this discussion.

We are now six years on from the policy launched …. in 2010 to mend the hole in the nation’s finances caused by an under-regulated banking sector. Rather than calling on the responsible actor, the financial sector, our poorer citizens have been chosen and the costs of the welfare state have been cut in the name of ‘austerity’. The film shows how the institutions of our welfare state, designed after World War II to provide a common bond of resilience and social security for us all in our times of vulnerability, are being turned into weapons of stigma, humiliation and social division.

I, Daniel Blake makes it clear that if Britain is to move on from this shameful position, it must replace austerity and referral to ‘the Decision Maker’ with humanity and presumption of entitlement as the principles with which official systems treat the most vulnerable in our society.

References

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Palgrave Macmillan; London.

Stuckler, D. and Basu, S. (2013) The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills. Allen Lane; London.

Szreter, S., Kinmonth, A. L., Kriznik, N. M. and Kelly, M. P. (2016) ‘Health, welfare, and the state—the dangers of forgetting history’, The Lancet. Vol. 388, No. 10061. Pp. 2734–2735.

Watts, J. (2016). I, Daniel Blake: Iain Duncan Smith slams Ken Loach's benefits sanctions film. [online] Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/i-daniel-blake-iain-duncan-smith-ken-loach-response-criticism-benefits-sanctions-film-unfair-a7384306.html [Accessed 27 Feb 2017].

Further resources

- Simon Szreter’s reflection on I, Daniel Blake

- Cathy Come Home, Ken Loach 16 November 1966

- Don't Mourn — Organize!: Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill.

- Money Box BBC radio 4 Feb 22nd 2017, Sanction busting Frank Field

- Advice from Citizens Advice Bureau on your ESA: “An independent medically qualified assessor (sometimes called a healthcare professional) will check how your illness or disability affects your ability to work. They use the information you've given on your ESA50 form and also draw opinions and make assumptions from what you do on the day”.

- The meaning of health professional given by ATOS: “Health Professionals (physiotherapists, nurses, occupational therapists and paramedics) who carry out PIP consultations and produce reports for the DWP.”

Clinical students’ dinner

Clinical students’ dinner

On Sunday 17th April 2016 the Reading Group held a dinner for final year clinical students in the college. This was an opportunity for the students to reflect on issues relating to health inequalities and public health in an informal setting and to engage in discussion with senior academics who work in these areas.

We had a very lively discussion which ranged from considering the impact of taxes on alcohol and sugar, to the influence of industry (food, drink, tobacco) on government policies which would then impact on health, to thinking about the role of the doctor in the community.

We wish all the clinical students well with their final placements and upcoming exams.

Health panel event

Interdisciplinary perspectives on the transmission of health advantage and disadvantage – panel event

On Friday 12th February 2016 we held a joint event with the St John’s Medical Society which explored the transmission of health advantage and disadvantage from three different disciplinary perspectives.

The event was chaired by Professor Ann Louise Kinmonth (Emeritus Professor of General Practice and Fellow of St John’s College), and the three speakers were Professor Graham Burton (Professor of Physiology of Reproduction and Fellow of St John’s College), Professor Larry King (Professor of Sociology and Political Economy and Fellow of Emmanuel College) and Tom Ling (Emeritus Professor Public Policy, Head of Evaluation at RAND Europe), all members of the St John’s College Reading Group on Health Inequalities. Minaam Abbas, President of St John’s Medical Society, acted as Discussant. The session comprised short talks by each of the speakers and concluded with a discussion with the students, and a summary of key points by Minaam.

Professor Burton gave a biological perspective, drawing attention to the long biological trajectory of many diseases. He explored the determinants of growth restriction in foetal life and the significance of this for lifelong health trajectories through developmental programming and described the intergenerational transfer of information (from gene environmental interaction) from grandmother to daughter to granddaughter, and even from father to infant via sperm cytoplasmic messenger RNA.

Professor King discussed the sociological contribution to understanding the transmission of health advantage and disadvantage. He highlighted three main points: that sociology emphasised the need for contextual and temporal analysis; the importance of the life course in understanding health and disease at different ages and phases of life; and the way the sociological perspective avoids an overly deterministic view of disease.

Tom Ling discussed the role of health services. He asked why health services can be designed in ways which make them less amenable to address inequalities in health compared to other types of interventions.

In the discussion the students focused on solutions and particularly the role and importance of education of the public in general and in improving behaviours related to health in order to prevent the transmission of health disadvantage. Improvements would be made to education about health specifically, but also to the wider education system to allow individuals to have better access to good quality education. The students were challenged on their assumptions that this would lead to increasing employment and better health as a consequence. Professor King asked if there were 95 bones available for 100 dogs, whether education of the dogs was the best solution, and criticisms of education as the main solution were explored.

Minaam Abbas concluded the event by identifying key areas where medical students could act to reduce inequalities in health:

1. They could come to events like this to become more aware of the existence of health inequalities, and what this means for them when they come to practice as doctors.

2. They should consider which patients are likely to be from vulnerable or disadvantaged groups and work towards improving their quality of care for such patients, for example by spending more time listening and signposting to other support systems available.

3. By recognising the power they hold in the communities in which they work, particularly when working in disadvantaged areas, they should consider their role in working with other organisations in their area in order to improve health in their community.

5. Finally, doctors need to better understand the social determinants of inequalities in health both at a local and global level and work towards reducing inequalities across the world.

Medical Society Essay Competition

St John’s College Medical Society Essay Competition

This year the St John’s College Reading Group on Health Inequalities was closely involved with the Medical Society Essay Competition.

The overarching theme for the competition this year was health inequality, and members of the Reading Group were consulted about setting the question and marking the entries.

The question for first year students was:

"Poorer people get sicker because of their behaviour." Discuss the evidence for and against this statement.

We were delighted to announce the results at the Annual Medical Society Dinner on Friday 29th January. The winner was Manel Patel and the runner-up was Ashwin Vankatesh.

Read Manel Patel's essay here and read Ashwin Wankatesh's essay here.

Student Essay Collection

Student Essay Collection

Website publication showcasing student writing on inequalities in health: call for titles

The St John’s College Reading Group on Health Inequalities includes Fellows from history (Simon Szreter, Robert Tombs) medicine and biology (Graham Burton, Ann Louise Kinmonth) and sociology (Mike Kelly, Natasha Kriznik research associate) and Fellows from other colleges in psychology, philosophy, political economy, epidemiology, and health services. We have been working together for the last year, exploring the power of interdisciplinary perspectives to illuminate our understanding of the persistence of health inequalities in communities over time and consider implications for public policy.

This year the Reading Group has been funded by the College Annual Fund to write up our work, and to include students in writing. It is with great pleasure that we therefore invite students to submit proposals for short articles to be included in a website collection entitled Interdisciplinary Reflections on Health Inequalities.

This Collection will showcase work of St John’s students, both undergraduate and postgraduate, relating to inequalities in health. The collection will be made available on the college website in Lent term alongside the writings of the Fellows.

This call for titles is open to students in the college regardless of discipline. If you have something to say about the causes, persistence or resolution of inequalities in health from a single or interdisciplinary perspective, from arts to sciences, contemporary or historical, local or global, philosophical or practical, and are keen to gain some academic writing experience then this is something for you! The final articles are expected to be between 500-1000 words in length, and we can offer editorial support throughout the process.

Ideas for writing inspiration include but are not limited to:

- A summary of existing research you are conducting, for example for your dissertation or thesis, and any key findings and their implications

- Developing a point or idea in an essay you have already written for your degree

- A short commentary or critique of a contemporary policy intervention relating to health inequalities, or of a theoretical or philosophical perspective used to analyse health inequalities

You might find inspiration from another source, or you might have an original idea for how you want to write or format your article – all ideas are welcome! The papers that the Reading group have considered, and a wider set of sources, can be found here and might act as a helpful starting point for your essay.

Please note: This essay Collection is not the same as the Medical Society Essay Competition which will also be running this year with the support of the Reading Group. This Collection is open to any student (not just medics) in St John’s, undergraduate or postgraduate, with the aim of providing a platform for existing research and thinking in the college on health inequalities. There are no set questions or areas which we want you to discuss. In addition the two essay calls are not mutually exclusive: you may submit work to both if you wish.

If you are interested in being involved in this project then we invite you to submit a title and short description to Dr Natasha Kriznik (nmk33@cam.ac.uk) by Friday 11th December 2015. We only need a brief outline at this stage; no longer than 200 words. Natasha will then provide you with feedback and will be on hand to help with the editing of your article from the early stages to the finished product. Final articles to be included in the Collection will need to be submitted by Friday 29th January 2016.

*Please note that the call is now closed.*

If you have any questions then please do get in touch. More information about the Reading Group can be found on the college website in due course.