A researcher at St John’s has discovered the molecular structure of a key enzyme in severe diseases that he hopes will lead to better treatments for young patients.

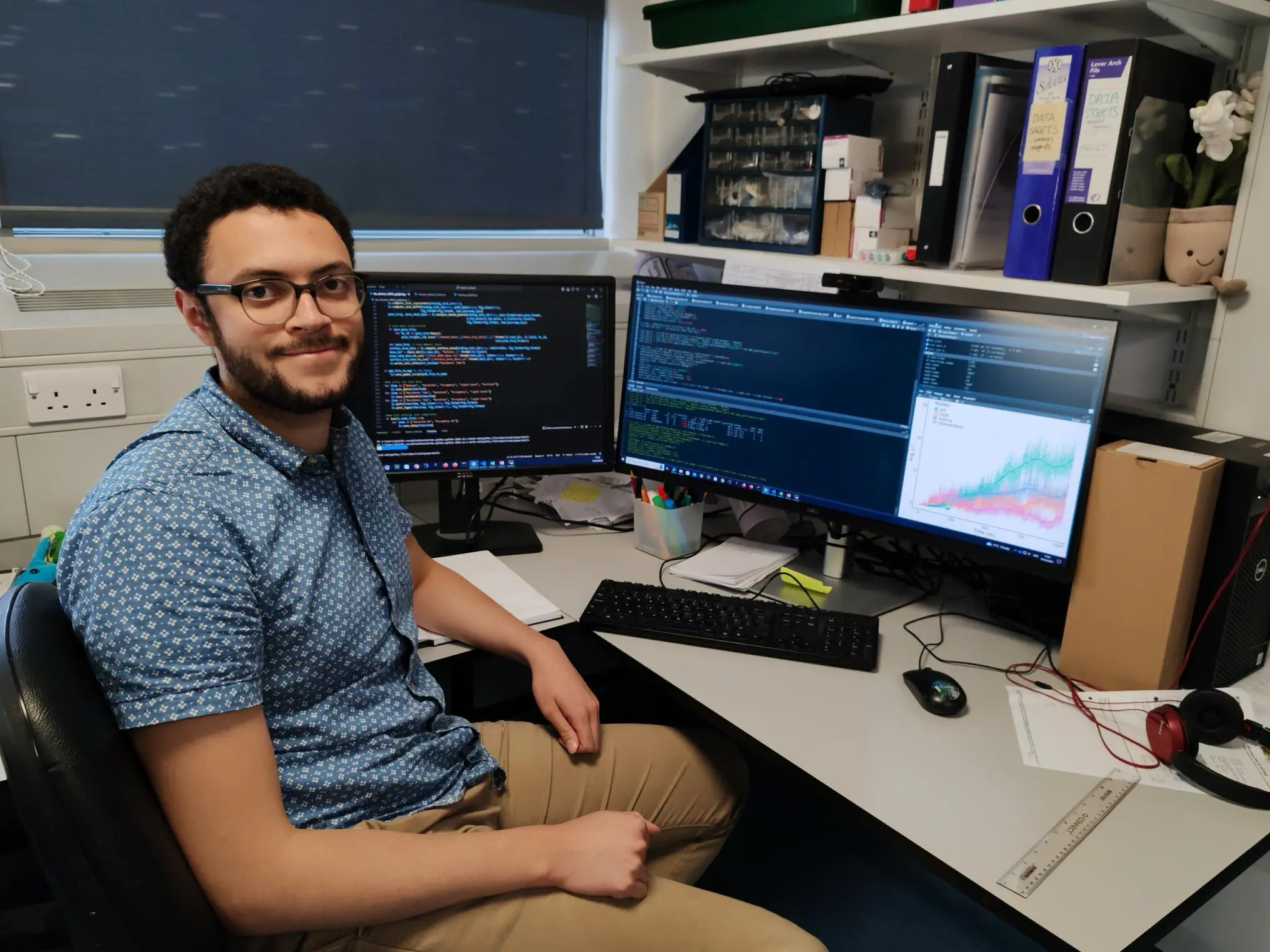

PhD student Jack Welland led a new study that found exactly what happens when an enzyme known as B4GALNT1 mutates, causing neurological disorders in children such as hereditary spastic paraplegia type 26 – a condition characterised by progressive leg stiffness, spasms, and cognitive impairment.

“Our motivation was to better understand how these diseases work and why they are caused by these faulty proteins”, said Welland.

“If these proteins lose function, they cause serious damage to neurons – nerve cells that send messages all over your body – which leads to the loss of limb function and intellectual disability.

“Importantly, we were able to identify for the first time the molecular mechanisms for how some of these mutations cause life-limiting neurological diseases.”

The research, undertaken at the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research (CIMR) and the University of Warwick, has been published in the journal, Nature Communications.

Enzymes are proteins that act as biological catalysts, speeding up chemical reactions within living organisms.

B4GALNT1 is involved in the biosynthesis of complex brain gangliosides – crucial components of cell membranes that are important for normal brain function.

Imbalances in the metabolism of B4GALNT1 not only cause hereditary spastic paraplegia, but the enzyme is also over-expressed in some cancers, particularly neuroblastoma – the most common cancer in babies and young children that originates outside the brain.

“The cancer cells in neuroblastoma produce far more of specific gangliosides made by these enzymes than normal,” said Welland, a third-year Michael House PhD Scholar in the Deane Lab at CIMR.

“Through our research we mapped the molecular structure of the enzyme, and a potential strategy now is to design drugs that can inhibit these enzymes to alleviate the children’s symptoms.”

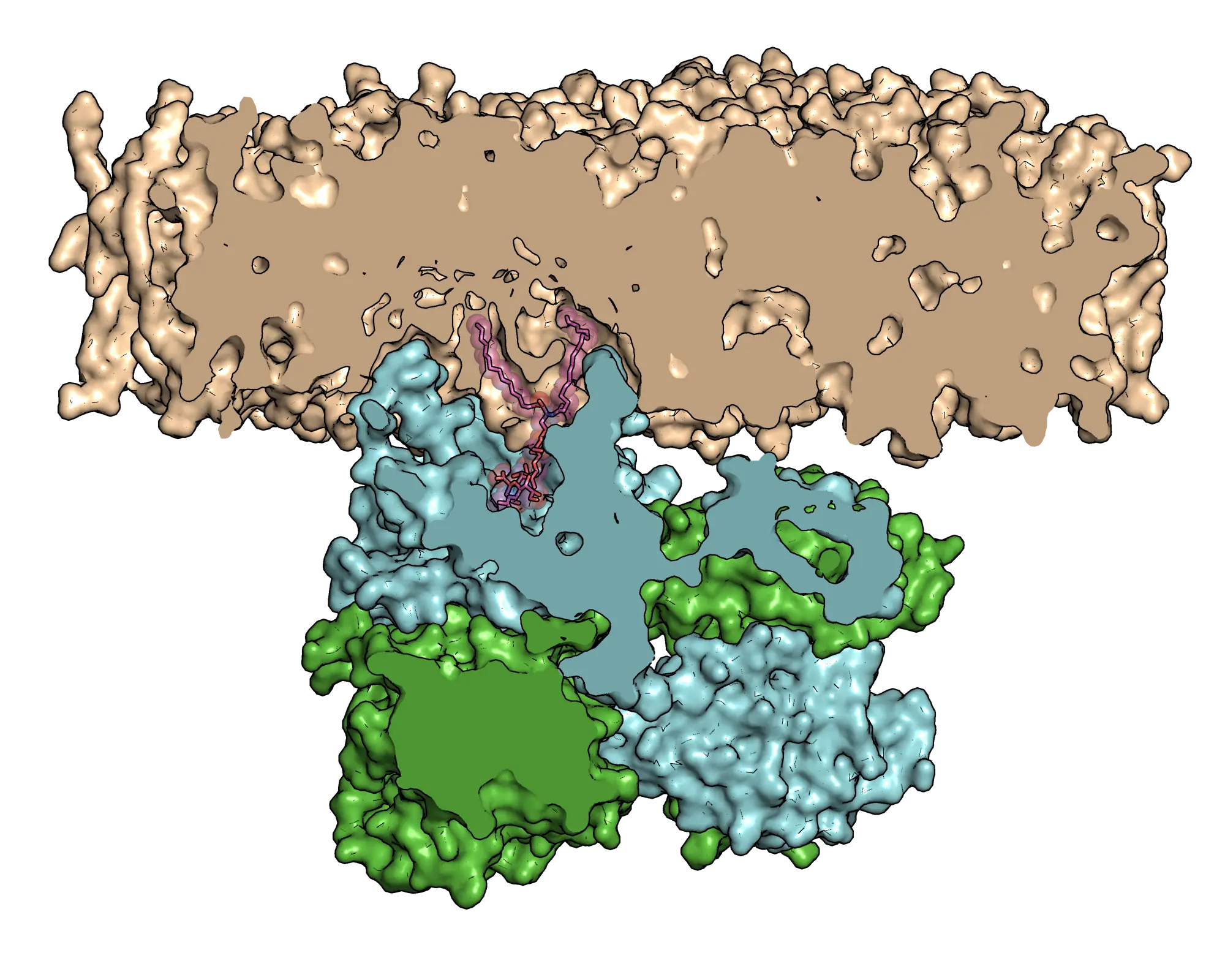

The researchers combined experimental and computational simulation strategies to investigate how B4GALNT1 functions. They found the enzymes have special loops they insert into cell membranes to draw themselves close to lipids, which make up the membranes.

The lipids with sugar groups joined to their heads are known as glycolipids, which organise themselves into two layers to shield everything within the cell. It is the glycolipids called gangliosides that the scientists studied to model the loss of protein function that causes neurological diseases.

"These particular lipids and lipid-synthesising enzymes are diverse biomolecules that have been considerably understudied at the molecular level before now,” said Welland, whose ambition to go into research was inspired by his older sister Alicia, who has multiple sclerosis.

“Our research to identify the molecular structure of the enzyme paves the way not only for new drug therapies but also for helping to understand their role in a range of diseases – including neurological diseases, cancers and in autoimmune diseases such as lupus.”

Welland is now developing computational tools for researchers to quickly see how metabolism changes for the special lipids in different diseases.

Welland, JWJ, Barrow, HG, Stansfeld, PJ et al: ‘Conformational dynamics and membrane insertion mechanism of B4GALNT1 in ganglioside synthesis’. Nature Communications, July 2025. DOI