Work, shopping, church and the pub kept different classes apart far more than ‘residential segregation’ in 1850s Manchester, a new study has found – undermining key assumptions about the Industrial Revolution.

By mapping digitised census data, new research by a St John’s College PhD student shows that many middle-class Mancunians including doctors and engineers lived in the same buildings and streets as working-class residents including weavers and spinners.

Historians have long assumed Manchester’s middle classes sheltered from the poor in town houses and suburban villas.

Now historian Emily Chung has found that more than 60 per cent of buildings housing the wealthiest classes also housed unskilled labourers. What’s more, more than 10 per cent of the population in Manchester’s ‘slums’ belonged to wealthier employed classes.

“Manchester’s wealthier classes did not confine themselves to townhouses in the city centre and suburban villas, as we’ve been led to believe,” said Chung. “I found doctors, engineers, architects, surveyors, teachers, managers and shop owners living in the same buildings as poor weavers and spinners.”

Chung argues that stark differences in work routines, recreational lives, shopping, public services, policing and pervasive discrimination isolated classes far more than residential segregation.

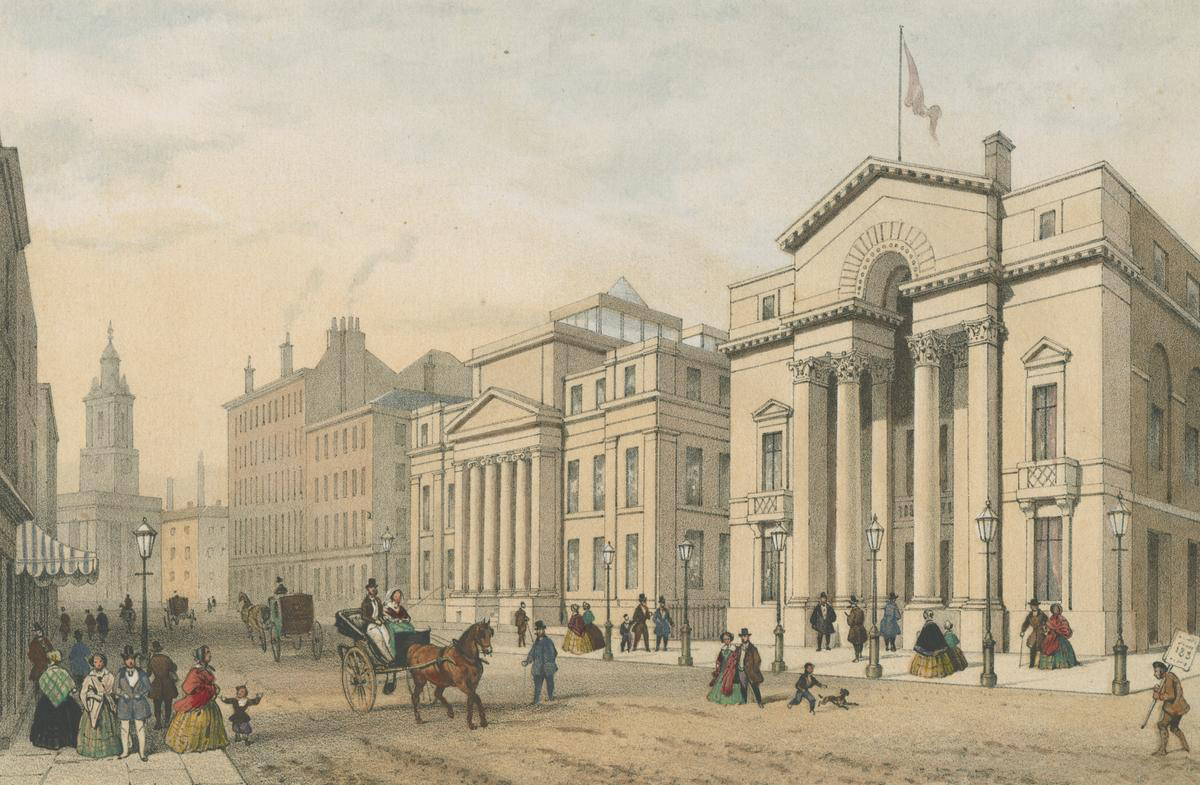

Friedrich Engels, the co-founder of Marxism, visited Manchester in 1842 and began recording examples of rampant inequality in the rapidly industrialising city.

He described a commercial core encircled by ‘unmixed working-peoples’ quarters, then the ‘middle bourgeoisie’ and further beyond, the upper classes. Many historians have relied on Engels’ account – preserved in The Condition of the Working-Class in England – but the conflation of class division and spatial segregation has come under increasing scrutiny.

Chung has used data from the digitised 1851 census to precisely map where people from different social classes were actually living in the city. Her findings, published in The Historical Journal, are startling and undermine the idea that different classes clustered in separate parts of the city.

“Segregation in cities remains a major concern in many parts of the world, including Britain, so understanding what people experienced in Manchester, one of the world’s first industrialised cities, is really important," she said.

“It teaches us that where we live matters but other factors can be even more influential. How people work, shop and relax divides social groups and can even make them invisible.”

Chung used ordnance survey maps, commercial directories and the 1851 census to link individuals to their specific residential address. She spent eight months painstakingly pinpointing buildings using known landmarks, including pubs, to guide her. At her most efficient, she could map 700 buildings per day, and then used this huge dataset to analyse spatial patterns.

Chung found more than 60 per cent of the buildings housing the wealthiest occupational classes were also home to unskilled labourers.

“This was a big surprise,” she said. “I started with the city centre and I thought the pattern might end there but as I moved onto the next part of Manchester, I kept finding this mixing. The most exciting moment was discovering that one in ten people living in Ancoats, the notorious working-class slum, were middle-class.

“Middle-class Mancunians might have seen their homes as stepping stones to something better, but architects and shop owners also valued the convenience of living close to where they worked. Commuter trains weren’t popular yet.”

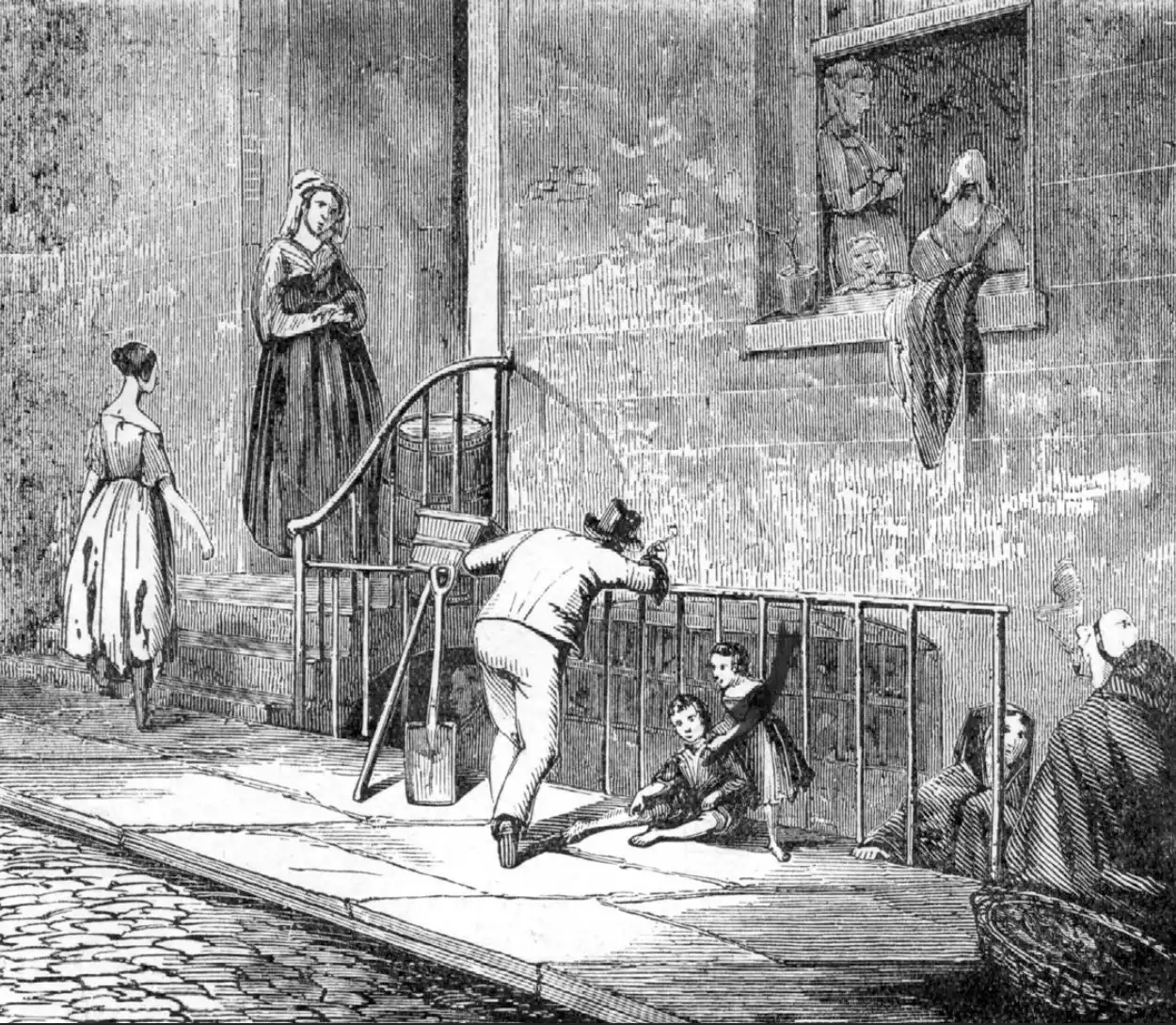

Chung argues that while different classes lived cheek-by-jowl, the construction, design, and maintenance of housing in 1850s Manchester limited interaction between them. With the city’s population booming, existing buildings were subdivided tenements. More respectable ground- and first-floor units could be rented to one or two middle-class households, while multiple poor families were crammed into filthy underground cellars.

The cultural and recreational habits of Manchester’s different classes reinforced segregation, said Chung, highlighting the opposing institutions of church and pub.

Occupational status also played a major role in segregating people, she argues. Before the introduction of labour reforms, many of Manchester’s semi-and unskilled workers put in 12-hour days, six days a week, trapping them inside while wealthier people were free to move around the city, working, shopping and socialising.

“What the Victorians ‘thought’ was happening in Manchester still matters, but comparing these perceptions against concrete geographic patterns means we can reconstruct life in the city more accurately. Then we can understand how those perceptions arose.”

Full story on the University of Cambridge website