Lessons from the past for disaster relief

Archaeological information about historic forms of house-building can teach valuable lessons to humanitarian workers who provide shelter following natural disasters, new research suggests.

Long-term perspectives on the ways people built and repaired their houses can reveal valuable insights into providing more effective humanitarian shelter, new research suggests.

Disasters such as the recent earthquake in Nepal can wreak devastation on entire regions and communities. One of the first priorities of humanitarian relief workers after these events is to provide shelter for those affected.

New research reported in the latest issue of Human Ecology suggests that aid organisations can benefit from considering long-term archaeological information about the diverse ecological and cultural factors influencing house-building traditions and choices. Dr Alice Samson, College Research Associate at St John’s, argues that historic building practices can reveal the complexity of resilience strategies, and teach valuable lessons to people rebuilding for the future.

Humanitarian relief workers tend to provide immediate short-term aid following large-scale disasters such as hurricanes, tsunamis and earthquakes. “The literature on disaster response suggests that in reality the humanitarian relief often fails to relate to practicalities of livelihood and social and economic life”, Dr Samson writes in the report.

Dr Samson’s research, conducted in partnership with the Centre for Urban Sustainability and Resilience at University College London and Leiden University in the Netherlands, looked at 150 excavated structures at sites across the Caribbean. The researchers also examined sixteenth-century sketches and reconstructions of houses built by Spanish Conquistadors on Haiti and Cuba in order to determine what features made these constructions so well-adapted to the variable climate conditions of this region.

Working with engineers as well as archaeologists, Dr Samson’s team discovered that a distinctive “Caribbean architectural mode” emerged around 1,400 years ago, the basic features of which remained fairly constant until European colonisation in the sixteenth century. This architectural style served to effectively meet the needs of the community and deal with cyclical environmental hazards as well as historic and cultural changes.

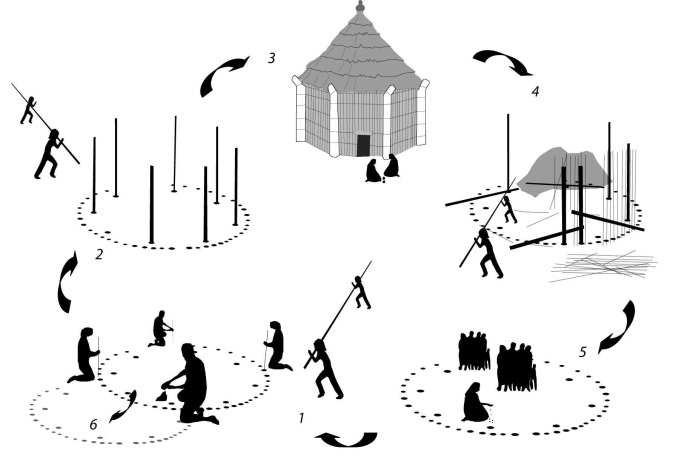

An excavation of the settlement of El Cabo in the Dominican Republic, for instance, revealed circular houses, between six and 10 metres across. These structures, which consisted of an outer wall of closely spaced posts and an inner ring of larger roof-bearing posts, were very effective at dealing with the high winds, rain and heat of the Caribbean. Wind exposure was reduced by facing the doorways inland, locating homes in an irregular pattern, and using windbreaks to partition houses from one another.

These houses, and others like them, lasted for centuries, being rebuilt and repaired over time yet with the essential characteristics of the building remaining the same. For Dr Samson, sites like this show that “shelter must be considered as a process, not an object”.

This research reveals new information about how past communities coped with severe weather and natural disasters. Dr Samson also believes that it can shed light on how modern-day communities struck by such disasters can be better supported by humanitarian efforts in the future by considering the longer-term factors involved in choices about houses and settlement, rather than starting the clock at the time of disaster. Dr Samson said: “We hope that this long-term regional analysis of house features might contribute to greater engagement between archaeologists and those responsible for building, or rebuilding, the present”.

Dr Kate Crawford, co-author of the report and former Shelter Field Advisor for CARE International, argues that “humanitarian decision-making often happens in a context of scant evidence and overwhelming data. This was one of the challenges faced in the response to the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. What we need is a better appreciation of strategic questions, research on alternatives such as repair, and support for local responses”.

The full report, titled “Resilience in Pre-Columbian house-building: a dialogue between archaeology and humanitarian shelter”, is published in the latest issue of the interdisciplinary journal Human Ecology, which can be accessed online at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-015-9741-5.

-ENDS-