Discover the latest news and groundbreaking research from St John’s, where big ideas shape the future. From pioneering scientific discoveries to thought-provoking academic insights, explore how our community continues to push the boundaries of knowledge and innovation.

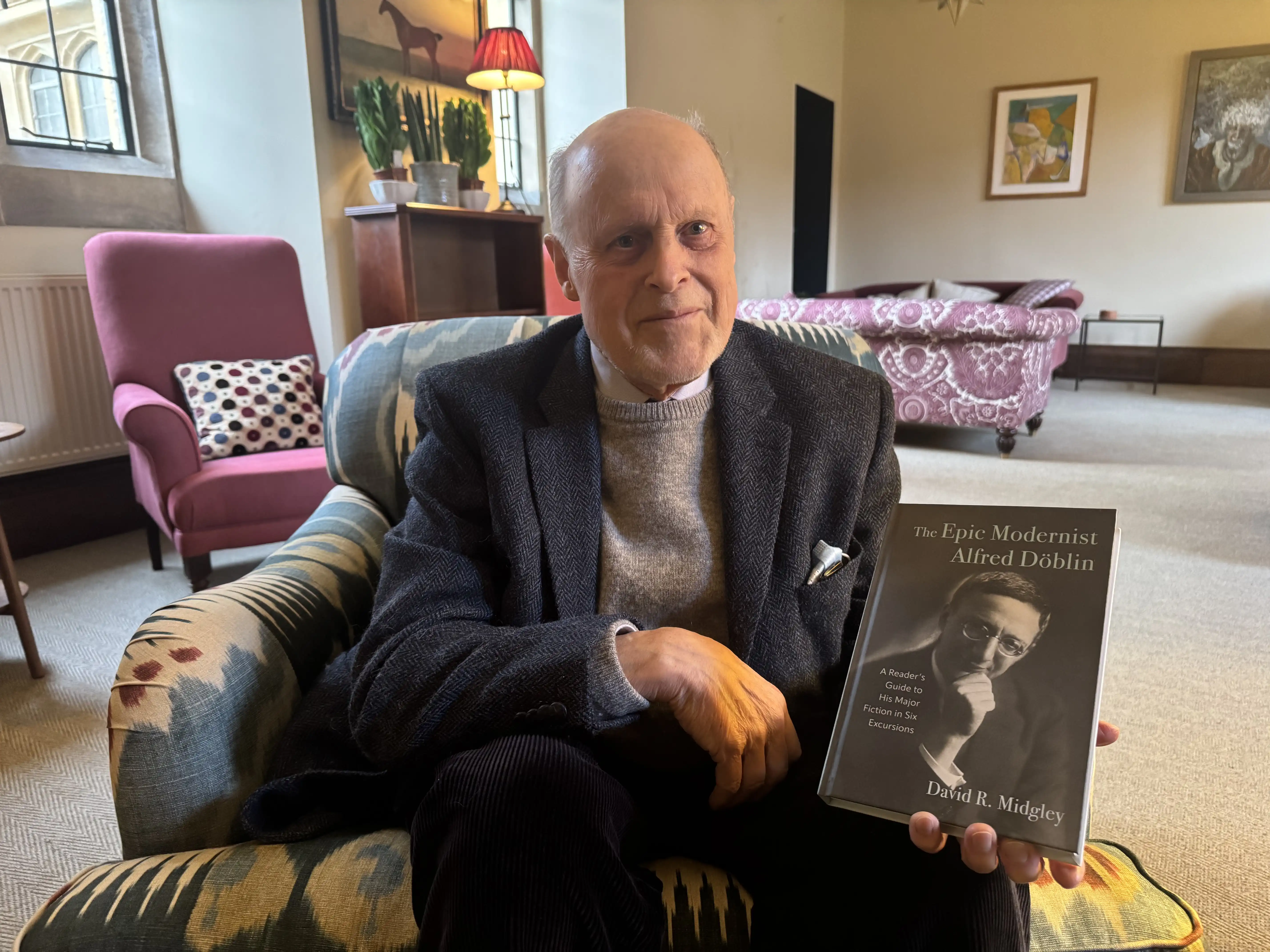

A new book argues that Alfred Döblin was one of the boldest writers of the 20th century and yet the English-speaking world is largely unaware of him

“We are throwing away extraordinary amounts of useful energy every day – and we don’t need to,” says Professor Andy Woods FRS, lead author of a major new Royal Society study

Seven Cambridge researchers, including St John’s statistician Professor Richard Samworth FRS, have been appointed Fellows of the Academy for the Mathematical Sciences

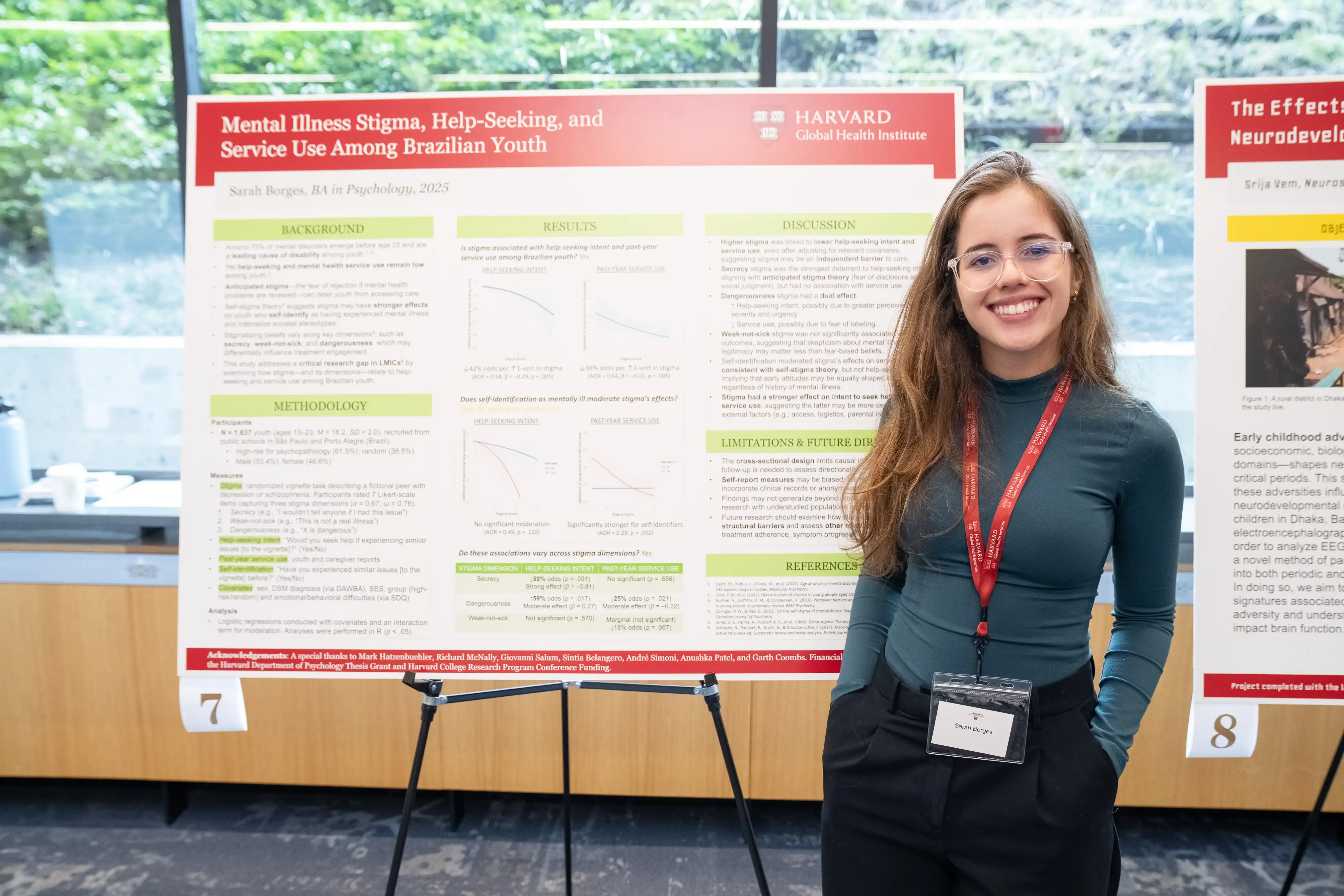

Rising star at St John’s College recognised by global brand for her drive to improve youth mental health in Brazil and beyond

Professor Gideon Henderson CBE FRS, an Honorary Fellow of St John’s, will deliver the free lecture on Tuesday 3 March 2026

Landmark research, co-led by St John’s College psychologist, aims to see whether restricted use of online platforms reduces anxiety and improves wellbeing

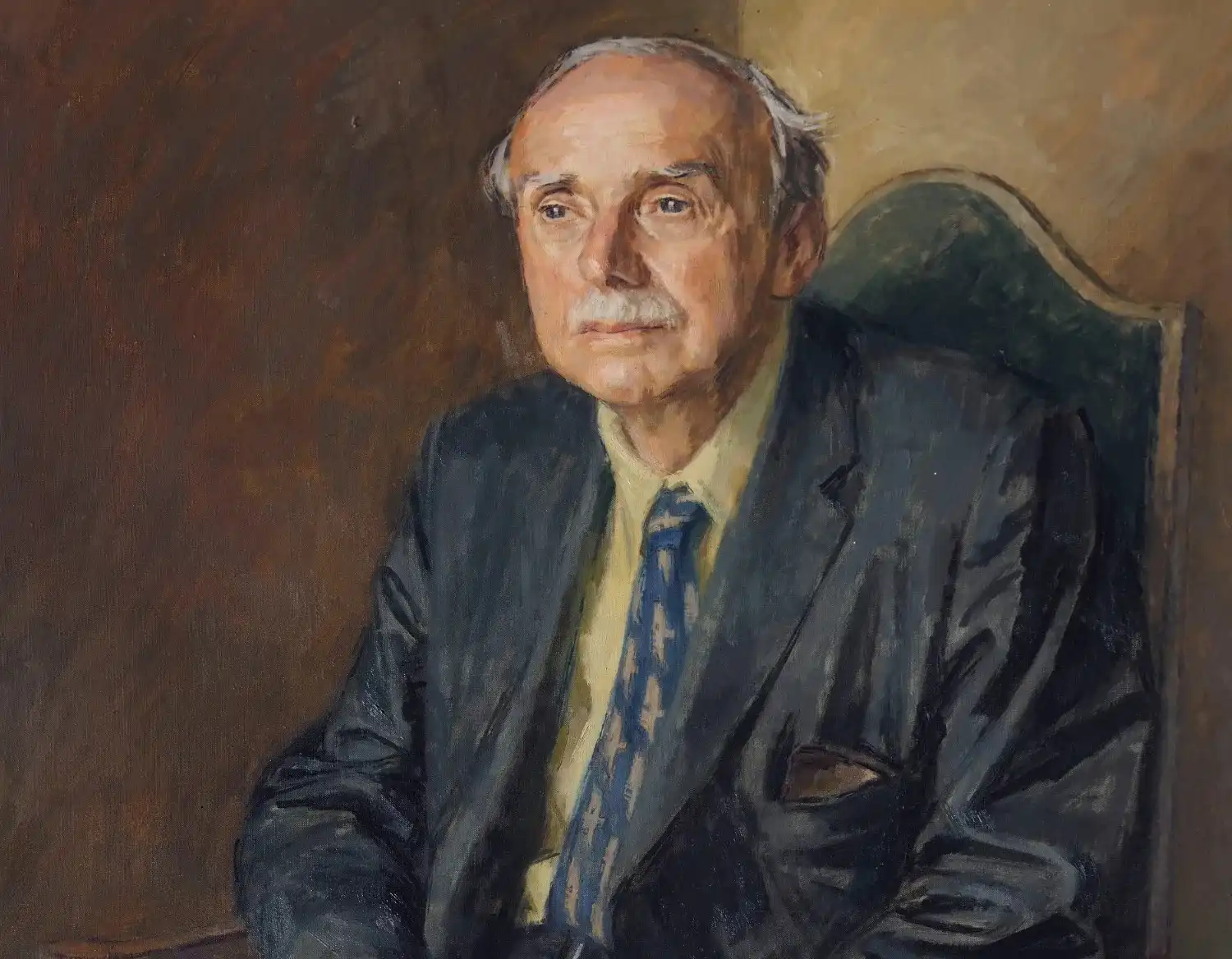

Former St John’s College Senior Tutor renowned for his work for people with psoriasis and other debilitating conditions is remembered after his death aged 84

Two renowned geochemists, a conservation scientist, a public health director, a musician and a LGBTQ+ campaigner receive accolades in King’s New Year Honours 2026

World-leading radiologist will explain innovative and streamlined ways to screen women at higher risk of breast cancer in this year’s Linacre Lecture at St John’s College

%20Lisboa.webp)

Cambridge academic examines how physical and psychological adversity shaped the lives and work of six influential artists and writers

Nick Jones reveals the ingredients that make comedy film Nativity! so popular and his career path from St John's Law student to making movies

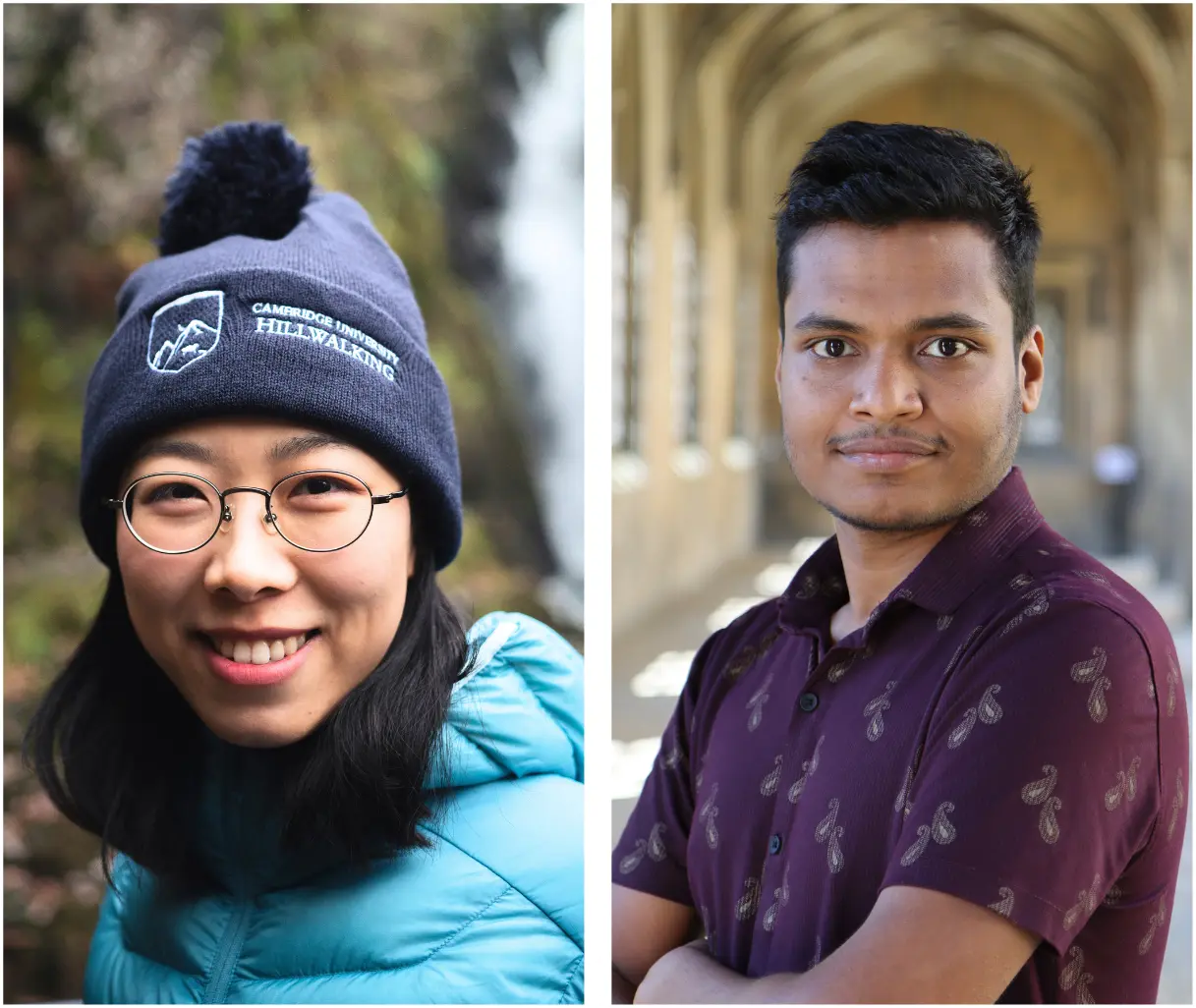

Researchers co-led by St John's College postgraduate call for urgent regulation after developing tool for artificial intelligence systems

Dr David John Haldane Garling, known as Ben, wrote core course textbooks and was ‘a pillar’ of College and University life

A St John’s postgraduate who studied while herding cattle as a child in Uganda has turned the challenges of his path to Cambridge into a book about resilience

‘Brilliant’ writer and musicians, maths star and sports captain win College prizes for their exceptional achievements

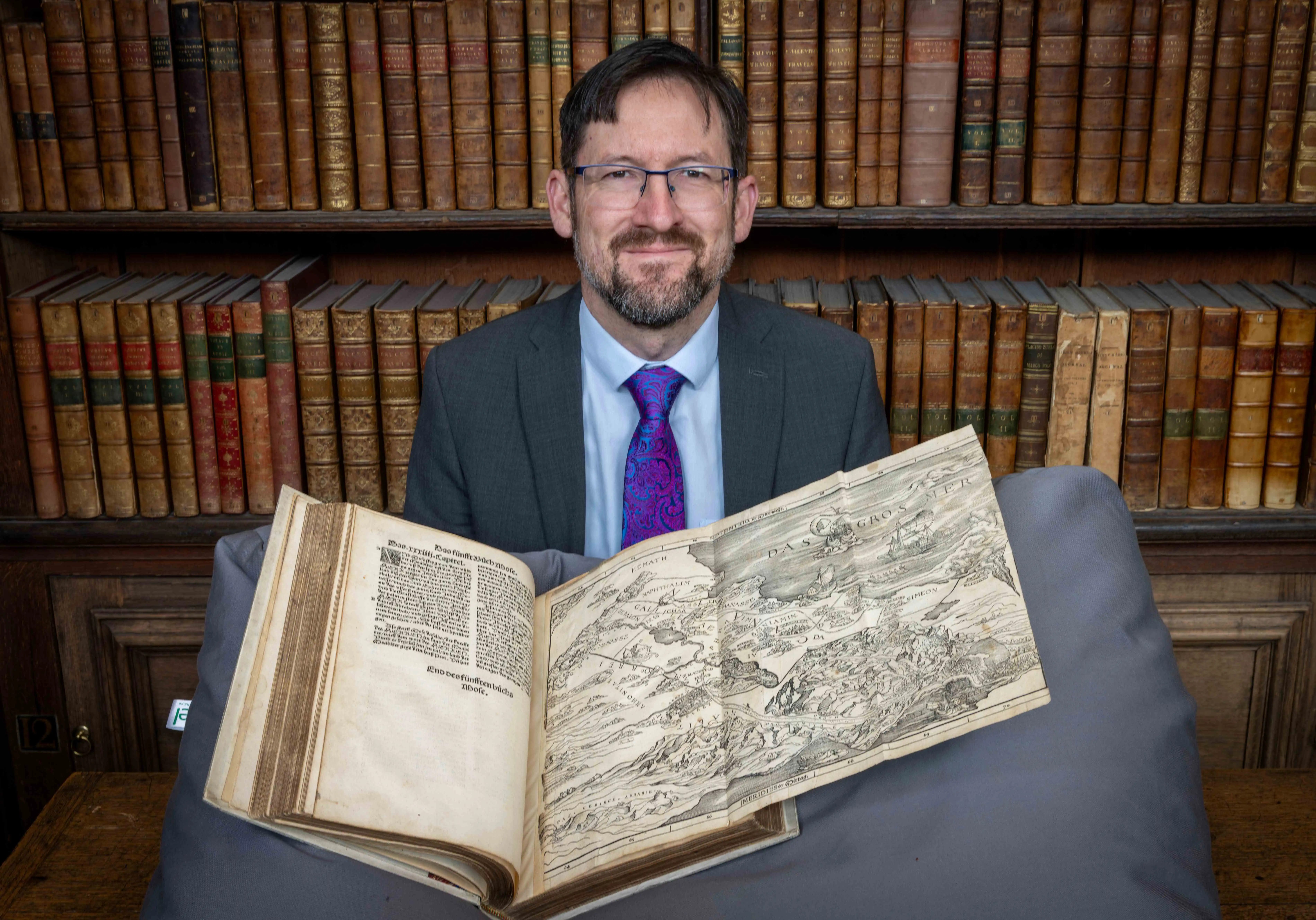

Cambridge-held map published 500 years ago led ‘revolution’ in meaning of boundaries, says St John’s College academic

New sessions at St John’s give students the opportunity to create, experiment and play, whatever their musical background

Meet Will Duckett, a St John’s College Psychology PhD student researching the phenomenon of mental imagery and its impact on memories

Full undergraduate funding will enable exceptional international students who need financial support the opportunity to join St John’s College

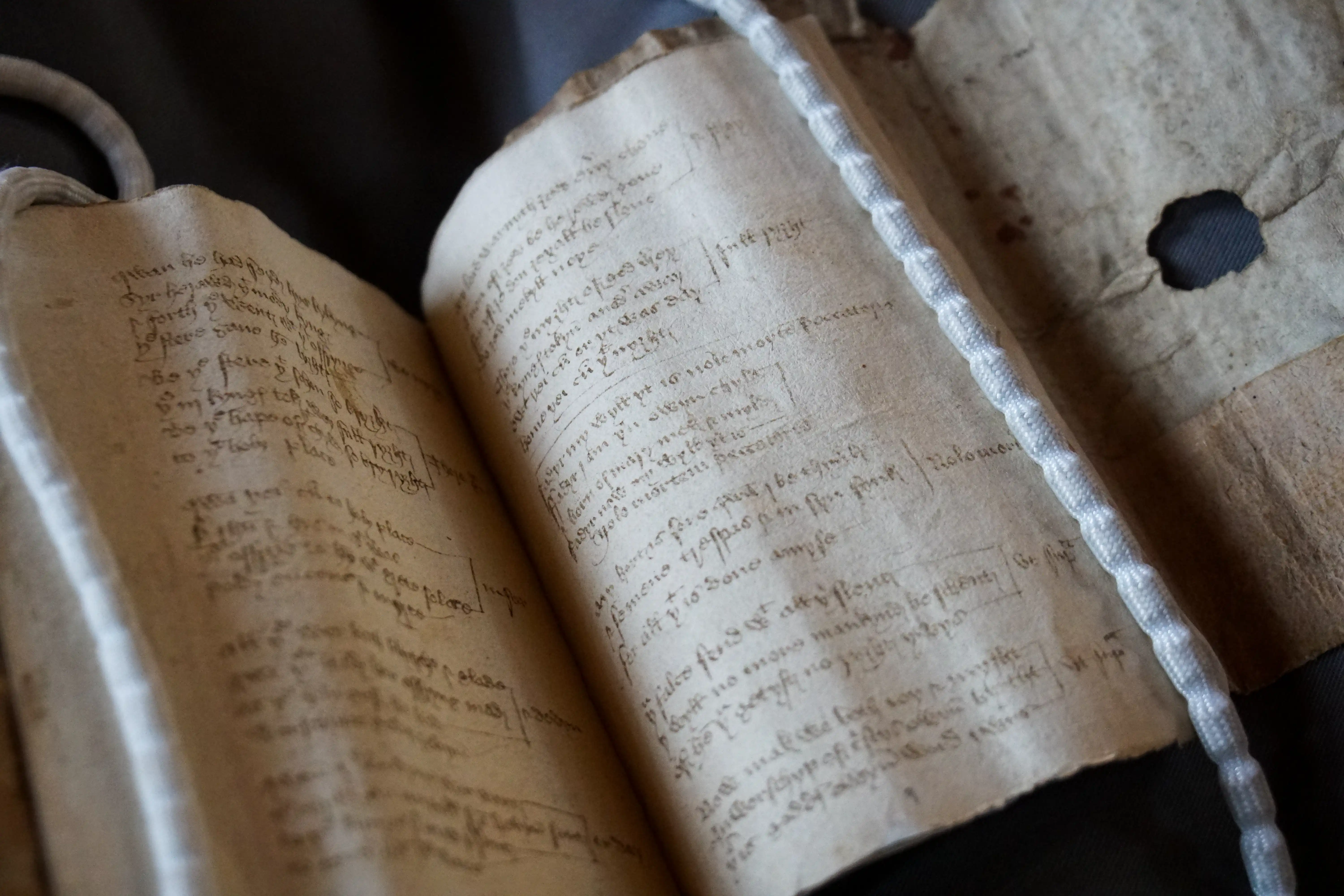

The 15th-century carol text will be brought to life at the Advent Carol Services at St John’s College

Honour for neuroscientist who discovered how to identify patterns of consciousness in coma patients

St John’s physicist co-leads research that could revolutionise manufacture of cheap electronics and solar cells

Sir Harpal Kumar, President International of biotech firm GRAIL, and Honorary Fellow of St John’s, will deliver inaugural talk on Monday 24 November at 6pm

A new spine-chilling collection of ghost stories takes readers on a terrifying tour through Britain’s Gothic past

World leaders at the annual UN climate crisis meeting learn how Cambridge researchers, led by a St John’s academic, empower farmers to innovate

Meet St John’s College graduate Rowan Saltmarsh who is fulfilling a lifelong ambition to forge a career in Formula One

Since Paul Dirac, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist from St John’s, first co-founded quantum mechanics, there has been a century of scientific discovery

Part of a 500-year tradition, the new cohort signed the Scholars’ Book alongside historic names such as the poet William Wordsworth and former Prime Minister of India, Manmohan Singh.

.jpg)

Award-winning Vice President of Research at Google DeepMind, Professor Zoubin Ghahramani, awarded an Honorary Fellowship

A postgraduate researcher at St John’s College says the structure governing cooperation across the UK lacks transparency and oversight

New family, couples’ and single-occupancy accommodation available following major investment in postgraduate homes

Fellow researching architecture of Indigenous people of the Nordic countries and Russia among academy's new cohort

St John’s scientist leads mother and baby mental health project spanning climate science, psychology, and perinatal wellbeing

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Philippe Aghion in recognition of his pioneering research on innovation, growth, and the dynamics of creative destruction

St John’s PhD student will lead University workshops focused on digital research methods and tools

St John’s historian uses census data to show many middle-class Mancunians lived in the same buildings as working-class residents

A bitesize digital series celebrating some of the UK’s most original thinkers has been launched to showcase the power and public value of research

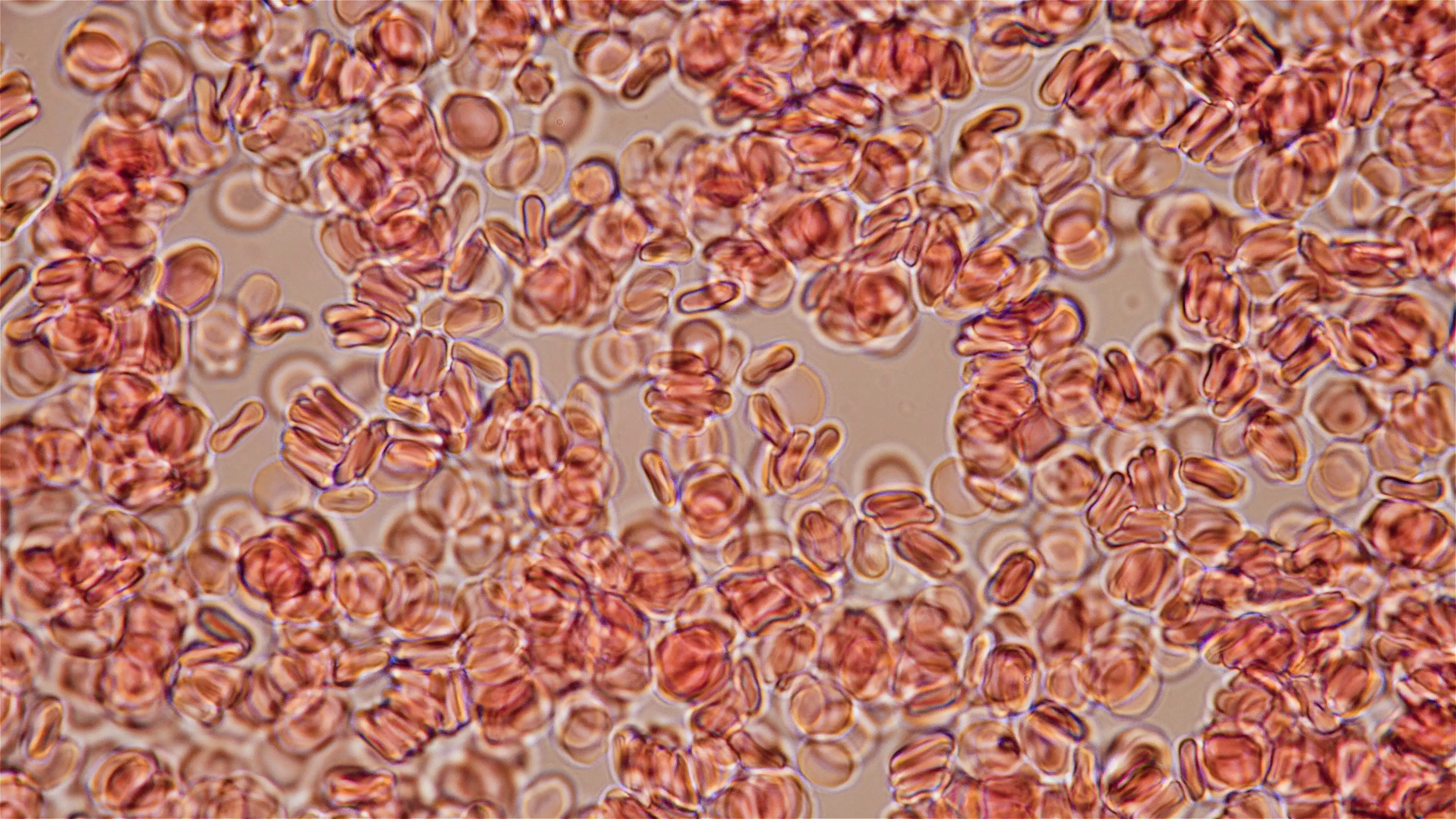

Discovery holds potential to simulate blood disorders like leukaemia, and to produce long-lasting blood stem cells for transplants

Sex, ambition and betrayal – the ingredients of a modern political scandal were alive and well in Ancient Rome

St John's researcher develops sustainable way to make the chemicals found in thousands of products – from plastics to cosmetics

New St John’s punt named in honour of evolution pioneer Louis Leakey

Author among 10 established and new writers in running for £25,000 award hailed ‘world’s best poetry prize’

“We have a long history of educating people who have changed the world”

Cambridge scientists discover how probiotics may help prevent miscarriages, gestational diabetes and preeclampsia

Current and rising stars of academia will teach and carry out independent research at St John’s

St John’s academic and former national cricketer says his affordable bamboo bat design will make cricket more accessible worldwide

.webp)

“You can't try new things if you don't take risks. Not everything works out. But even when that happens you learn a lot”

“Our findings point to a survival gap that begins before patients even reach the operating theatre”

Professor Robert Mullins co-founds major new artificial intelligence initiative to drive UK research and innovation

Exceptional academic performances rewarded as undergraduates secure top marks in their Triposes – Cambridge’s rigorous undergraduate degree courses

“The REF is one of the most important means for identifying excellent research wherever it occurs in UK universities”

‘Hidden disease’ that kills thousands of women and babies a year to be tackled

St John’s academic rated highly for going ‘over and above’ in her role

“We look forward to building on our strong tradition of philanthropic generosity”

Distinguished role bestowed upon poet described as ‘one of the best writers in Ireland today’

Mapping of a key brain enzyme reveals links to childhood disability and cancer – and could unlock new drug therapies

Physicists receive grant to pave way for groundbreaking quantum technologies

Network led by a St John’s biologist works to transform understanding of women’s medical research and care

Executive MBA student recognised for upcycling waste lead-acid batteries

Historic boat club’s May Bumps win is highlight of bicentenary celebrations

Academics secure major support for pioneering work in quantum optical science and dyslexia

St John’s has scooped the highest accolade in the University of Cambridge’s Green Impact awards

.webp)

New approach led by St John's Fellow is improving survival rates for women with breast cancer

.webp)

A state-of-the-art facility designed to push the boundaries of what is possible

“I feel an immense gratitude to my team for all the wonderful science that we do together”

New research by a College Fellow is challenging assumptions about how best to use renewable electricity in green ammonia production, offering ways that could make it more cost-effective

Online technologies from social media to AI are changing too fast for scientific infrastructure to gauge their public health harms, say two leaders in their field

Seven eminent individuals with expertise ranging from miscarriages of justice, marine climate change, and artificial intelligence to the history of spycraft have been elected as Honorary Fellows of St John’s College

Richard’s contribution to methodological and theoretical statistics has been truly outstanding, as have his contributions to the statistical profession

A ‘stellar’ mathematician from St John’s is one of the first winners of the David Cox Medal for Statistics, which commemorates the work of a ‘giant of a statistician’ and alumnus

Lady Margaret Boat Club’s 200-year legacy is a story of exceptional achievement, not just at St John’s, but in the world of rowing

"It’s like working with a Lego set with every kind of shape you can imagine, rather than just rectangular bricks"

A historic organ originally constructed by ‘Father’ Henry Willis is due to be installed in the Chapel at St John’s College

Tiny copper ‘nano-flowers’ have been attached to an artificial leaf to produce clean fuels and chemicals that are the backbone of modern energy and manufacturing

This grant will allow us to understand how our bodies react to these modern medicines

Dr Elisabeth Kendall, Mistress of Girton College, to speak on ‘The Role of Yemen and the Houthis in the Broader Middle East Conflict’

Up to 70 per cent of weight differences are genetic, with common variants influencing appetite and metabolism, a pioneering research scientist has explained in a historic lecture at St John’s College

Cambridge researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts it into sustainable fuel, using sunlight as the power source.

The Mathematical Tripos is famously difficult