"Continuously creative" genius celebrated in new exhibition

A new exhibition in the Library at St John’s College, featuring never-before-seen material, has been launched to celebrate the centenary of prominent scientist Sir Fred Hoyle, best known for coining the phrase “Big Bang”.

Fred Hoyle was one of the twentieth century’s most creative and controversial scientists, always unafraid to question orthodox beliefs. Known as a populariser of science, the astrophysicist is probably best remembered for coining the phrase “Big Bang”. Now a new exhibition at his old Cambridge College has been launched to celebrate a hundred years since his birth.

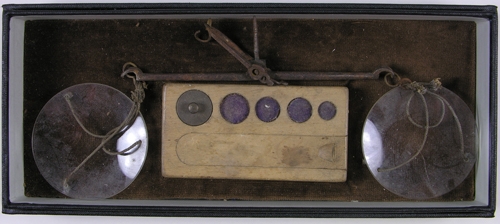

The exhibition features never before seen photographs and artefacts that shed light on Hoyle’s childhood in Yorkshire and the early influences that led him to a lifelong passion for science. Amongst the items showcased are the surviving pieces of Hoyle’s childhood chemistry set, which he used to make “glorious explosions” in his mother’s kitchen. His enthusiastic descriptions of his experiments, including one to make noxious phosphate gas, helped him to earn a place at Bingley Grammar School.

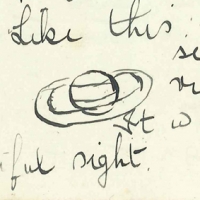

Also on display is a letter from Hoyle aged 15 to his father describing the first time he looked at the night sky through a telescope, and saw the rings of Saturn, which he described as “a beautiful sight”. Writing in his autobiography in 1994, Hoyle recalled when he first became aware of the night sky as a boy. He wrote:

Also on display is a letter from Hoyle aged 15 to his father describing the first time he looked at the night sky through a telescope, and saw the rings of Saturn, which he described as “a beautiful sight”. Writing in his autobiography in 1994, Hoyle recalled when he first became aware of the night sky as a boy. He wrote:

“I seemed to be in contact with the sky instead of the earth, a sky powdered from horizon to horizon with thousands of points of light…I remember looking upwards and deciding that I would find out what those things up there were”.

Born in 1915, Hoyle studied Mathematics at Cambridge before becoming a Fellow at St John’s College in 1939, a position he held until his death in 2001.

Hoyle’s interests in science ranged from asking “why does a cutting of a holly bush grow into an identical holly bush?” to being the father of “stellar nucleosynthesis”, the study of how chemical elements form within stars.

In the mid-1950s Hoyle became the leader of a group of talented experimental and theoretical physicists who met in Cambridge. This group, which included Margaret and Geoffrey Burbidge and William Alfred Fowler, worked together over almost a decade to revolutionise scientific understanding of how elements were formed.

In 1957, the group published a joint paper, known simply as B2FH after the initials of its four authors. The paper was the first to explain systematically how chemical elements such as iron and carbon were forged, or “synthesised” from hydrogen and helium in the extreme heat of expanding stars, through the process of nuclear fusion.

Hoyle was deeply interested in communicating science to the public, eager to share the thrill of scientific discovery with a wide audience. He wrote books for the general reader, such as his 1955 work Frontiers of Astronomy, as well as making appearances on the television and radio to discuss the latest scientific ideas, always explained in plain language and with a broad Yorkshire accent.

It was on one such radio broadcast on the BBC in 1949 that Hoyle coined the memorable phrase “Big Bang”. Hoyle in fact rejected the theory that the universe began from an exploding singularity, in favour of the concept of “continuous creation” of matter in a steady-state universe. During the interview, Hoyle stated that the opposing theory was “based on the hypothesis that all matter in the universe was created in one Big Bang at a particular time in the past”.

When Hoyle gave a popular series of talks the following year, later published as The Nature of the Universe, he re-used the term “Big Bang” several times throughout. The name for the theory of cosmic expansion caught the public imagination and has been used ever since, despite Hoyle’s disagreement with the theory it describes.

In later life, Hoyle’s career was dominated by his often controversial ideas. He disagreed with the evolutionary theory that all life on earth originated with a common ancestor, and wrote Evolution from Space in 1982 setting out his alternative view: that life began elsewhere in the universe and continually reaches earth via comets, in a process called “panspermia”. Together with Chandra Wickramasinghe, Hoyle hypothesised that many viruses, including influenza and AIDS, may have originally come from outer space. The rise of Astrobiology today may be a result of Hoyle’s tenacity in questioning accepted views.

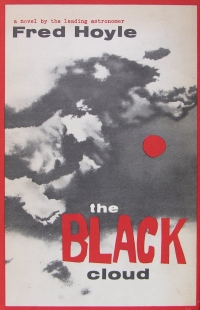

Hoyle was also a prolific science fiction writer, publishing 19 sci-fi novels, many in collaboration with his son, Geoffrey. His first novel, The Black Cloud, was praised by critics. The novel was originally written after Hoyle was unable to publish a scientific paper concerning the prediction of interstellar molecules in the galaxy. In the early 1960s, these molecules began to be detected, vindicating Hoyle’s theory, described in the book, that molecular clouds can exist in space. Writing a preface for the 2010 Penguin Classics reprint, renowned biologist Richard Dawkins called it “one of the greatest science fiction novels ever written”.

Hoyle was also a prolific science fiction writer, publishing 19 sci-fi novels, many in collaboration with his son, Geoffrey. His first novel, The Black Cloud, was praised by critics. The novel was originally written after Hoyle was unable to publish a scientific paper concerning the prediction of interstellar molecules in the galaxy. In the early 1960s, these molecules began to be detected, vindicating Hoyle’s theory, described in the book, that molecular clouds can exist in space. Writing a preface for the 2010 Penguin Classics reprint, renowned biologist Richard Dawkins called it “one of the greatest science fiction novels ever written”.

After Hoyle’s death in 2001, his wife Barbara donated her library of Hoyle’s artefacts, photographs and papers to St John’s College, to be held for future generations of scientific researchers and the interested public. The exhibition, called Continuously Creative: the Life and Legacy of Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001), brings together some of the highlights of this vast collection and through them tells the story of the life and work of this most influential and intriguing of scientists.

Fred Hoyle’s son, Geoffrey, who worked closely with the College to catalogue his father’s collection, said:

“It is heartening to see that one hundred years after my father's birth, St John's College is celebrating his achievements and making his works available to the public. The College, which was such a large part of my father’s life, has catalogued his collection of scientific papers, manuscripts, photographs, letters and notes, which are today being used by researchers from around the world. The exhibition offers a fascinating snap-shot into my father's scientific work and his personal life and interests”.

Continuously Creative: the Life and Legacy of Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) can be seen in the Library of St John’s College, Cambridge from Monday-Friday 9:00-17:00 until 20 April (closed on the Easter Bank Holidays). The exhibition is open to the public, free of charge.

More information about Fred Hoyle, including an Online Exhibition of items from the collection, can be seen on the Fred Hoyle Project webpage.